Sindhis place little importance on the caste system. The majority of people interviewed indicated that they belonged to the Lohana caste, but they usually only referred to themselves as Sindhi Hindus.

Excerpts from a Research Paper ‘From Traders to Workers: Indian Immigration in Spain’

Ana López-Sala

The history of the Indian community in Spain is fascinating not only for its peculiarity within the general dynamics of immigration to the country, but also because it is one of the least known migration inflows, despite being one of the oldest. Indian immigration to Spain began at the end of the 19th Century as part of a diaspora of Sindhi traders which, like other merchant communities, is dispersed throughout the world.

The first Indians settled in the Canary Islands during the second half of the 19th Century, many arriving from Mediterranean and coastal African cities. The first wave of settlers had a homogenous profile because their international mobility practices were linked to commerce, an activity carried out exclusively by Sindhi men, leading them to expand and settle in free zones and port cities throughout the world. They chose to settle in Spain’s Canary Islands due to business opportunities there, as well as the archipelago’s proximity to other settlement areas, such as Gibraltar and the Maghreb countries.

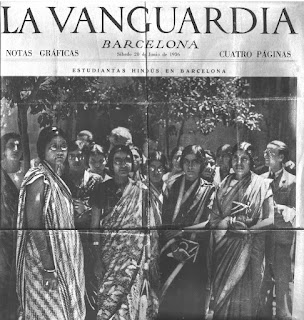

was one of a group of young ladies on a tour of Europe,

chaperoned by a respectable Scottish lady who lived

in Hyderabad. Quite a stir they created, in their elegant and

fashionable saris, from Norway to Spain and beyond!

They visited cultural sites and interacted with cultural

groups, and people were charmed by their poise and

flawless English. This clipping appeared on 20 June, 1936.

Captioned ‘Hindu students in Barcelona’, it went on to say,

“The group of Hindus students that is taking a study trip

through Spain has arrived in our city, visiting our museums,

our monuments and our teaching officers”. The photograph,

by Puig Farran, was taken at the Patio de los Naranjos de la

Generalidad. Image courtesy Kishni’s daughter, Bina Thadani. (Photo taken from Saaz Aggarwal’s article)

The community of early settlers numbered just over one hundred people, all male, who made frequent trips to areas near the Mediterranean and Northern Africa where they already had other businesses. The male heads of household, and in some cases eldest sons, also returned regularly to India to visit their families, who remained in Sindh, and for religious and social reasons.

The migratory flow of Sindhis to the Canary Islands increased during the first decades of the 20th Century, but it reached its highpoint at the end of the 1960s and start of the 1970s. The flow increased because the archipelago’s economy improved, activated by the boom in national and international tourism, and also due to the community’s struggles in other locations, including Sindh itself, which was left under Pakistani rule after the Indian subcontinent was partitioned in 1947. During this period the origins of new arrivals diversified. Sindhi merchants and workers arrived in Spain not only from India, but also from other countries where their trade diaspora had settled, including Hong Kong, Vietnam, Philippines, Curacao or Ghana.

Sindhi immigration in this period was family-based, although in the majority of cases the women came only after their husbands had been settled in the country for a few years. The vibrant economic situation of this period allowed some of the merchants established in the Canaries to expand their businesses to other Spanish provinces, such as Ceuta, Melilla or Malaga, and in Andorra, which also offer advantageous tax regimes. In Ceuta and Melilla their businesses flourished for several decades, employing many local workers, thanks to clientele from military bases and their families, who visited during oath of allegiance to the flag ceremonies. By the middle of the 1970s Indians owned more than 200 businesses in Ceuta and Melilla.

In the 1980s, the liberalization of exports and the loss of business opportunities in the Canaries caused by Spain’s entrance into the European Union led some Sindhi businessmen to move to other parts of Spain, such as Catalonia, Malaga and Andorra, in search of new opportunities.

Indian migration, with its diversity and evolution, is one of the few historic immigrant communities in Spain, a country that had received little immigration until the 1980s. Over the decades this flow has created a small, distinctive community of common Indian descent that includes very diverse national and legal affiliations (including natural and naturalized Spanish citizens, Indian citizens and citizens of other countries), and also an involvement in business activities (both as workers and owners). The small number of members of this community is in contrast with its economic importance; it was part of the business elite in the Canaries for decades and also played important role in Ceuta’s economy.

The “new Indian immigration”, much more recent and even less known, started in the 1980s and has grown significantly over the past few years, although its volume remains limited. The composition, economic activity and pattern of geographic distribution of this new migration are very different than that of the traditional Sindh immigration. For instance, it has highly varied origins: the majority of the migrants are Sikhs, but they also include Hindus, Muslims and Buddhists from northern India, especially Punjab and Haryana.

Today, Sindhis make up a small, transnational community with multiple national affiliations. Internally, the community is very cohesive due to a multitude of family and economic ties that transcend national borders, forming an intense social network through which goods, services, capital and credit, information and people circulate. Concepts such as nationality and “locality” do not form part of their identity, while economic practices and religious faith permeate and shape the community’s self-identity and sense of belonging. An extensive and multinational family, multilingualism and intense social relationships via the network are other aspects commonly mentioned as articulating their sense of belonging and reproducing their identity.

A long tradition and specialization in commerce, a strong sense of community and trusted networks in different parts of the world have facilitated the development of their businesses in Spain, first in the Canary Islands and later in other cities in Andalusia and Catalonia. The business sphere in the Sindhi world is exclusively masculine, although this situation can change slightly in the context of migrations, as has been observed in other countries in which they have settled. The role of women is limited to the domestic realm. However, they are in charge of maintaining the cultural traditions at the heart of the community’s identity, including matrimonies and religious practice. This is articulated through the temples of diverse branches of Hinduism. Notable branches in this regard are the Geeta Ashrams, Guru Mandir, and other centers in the Satnam Sakhi, Radha Soami or Sai Baba tradition in the Canaries, and the Hare Krishna Temple, the Radhasoami Satsang Beas Hindu Meditation Center and the Sai Baba Center in Catalonia. There are more progressive versions of Hinduism within the community, and others that are stricter and more conservative.

The field work carried out in the Sindhi community between 2006 and 2011 has also allowed us to establish a series of conclusions on the caste system among Indian traders settled in Spain and its links to the creation of identity. In general terms, Sindhis place little importance on the caste system. The majority of people interviewed indicated that they belonged to the Lohana caste, but they usually only referred to themselves as Sindhi Hindus. For example, among groups of traders residing in Spain it’s quite common for members of different castes to get married and to take meals together. The little importance placed on the caste system has also been observed in this community settled in other parts of the world. For instance, Dieter Haller’s study on Sindhi settled in Gibraltar underscores that one of the most noteworthy and distinctive elements of this community is precisely the lack of importance placed on the caste system, in contrast to all other Hindu groups.

However, the weak influence of the caste system on the structure of Sindhi social life was first indicated by Barnouw in the mid-1950s. In his opinion, the minimization of its importance was consistent with the religious and social traditions of Sindh, where the influence of Muslim doctrines of Sufism and Sikhism and of some reform Hindu currents such as Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj, which defend the abolition of this system, seem to have somewhat weakened class distinctions, resulting in a more liberal and eclectic religious practice. In addition, contact with different parts of the world, and other cultures have given this community a cosmopolitan attitude, including a great deal of tolerance toward religious and social diversity.

This is not the case with the Punjabis recently settled in Spain; for this group, the caste system is an important factor in the internal structure of the community and it continues to affect their social life.

There is very little integration of Sindhi merchants into Spanish business and social organizations. In the 1950s and 60s they created their own cultural associations, known as Indostanic clubs, which became one of the main meeting places of this community for years. Many economic agreements were carried out in these clubs, since they served as a place where local businessmen could meet with other businessmen who were visiting family or on business trips.

Conclusions

The Indian community currently residing in Spain is the result of various differentiated migration currents. The first flow, which occurred throughout the 20th Century, was characterized by Sindhi merchants and workers who settled in prosperous areas of Spain in order to take advantage of the business opportunities offered by the free zones and the boom in mass tourism. Although small in volume, this immigration has a long, well-established history in Spain and has had a great deal of economic success and obtained legal status. This community is highly visible in the business sectors of the locations in which it settled and enjoys a good reputation and strong institutional relations, despite maintaining weak social ties with the host society. The Sindhi community is articulated around Indostanic clubs, business activity and the practice of Hinduism, elements that are all more important to their self-identity than nationality and place of residence, as can be observed in other trade Diasporas. However, this group has gradually lost predominance within Indian immigration to Spain. At the end of the 1980s a new flow began to arrive from northern India, especially Punjab and Haryana. This new, far more diverse, medium to low-skilled and masculinized flow has settled in Mediterranean provinces to find work, particularly Catalonia and the Valencia Community, and has higher levels of irregularity.

______________________

Ana López-Sala, From Traders to Workers: Indian Immigration in Spain, CARIM-India RR 2013/02, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): European University Institute, 2013.