Sindhis systematically equate Sufism with secularism and universalism, echoing G. M. Sayed’s conception of mysticism.

By Julien Levesque

Sufism and the ‘struggle over representations’ in Sindh

The diffusion of Sufism as a marker of Sindhi identity does not go unchallenged. If images of shrine culture have spread in mainstream Pakistani media as symbols of ‘traditional’ Sindh, the conception according to which ‘Sindhis are Sufi by nature’ still seems mainly located within a certain educated middle class, particularly sensitive to the Sindhi nationalist imaginary.

G. M. Sayed’s writings gave a formal and explicit shape to the association of Sufism with Sindhi identity. They inscribed Sufism in a nationalist historical narrative that highlighted the continuous occupation of the lower Indus Valley by one people, the Sindhis, and the constancy of their culture from the days of the Harappan civilization. But if G. M. Sayed is seen as the rahbar, or ‘founder’, by Sindhi nationalists, it could be argued that his books in fact synthesized and condensed the work of a whole generation of Sindhis engaged in a broader process of identity construction during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, that drew on popular culture to craft a set of identity markers. While elected representatives saw their power increasingly curtailed (Tahir 2010, Talbot 1998), a new generation of Sindhi Muslim men educated in Sindh, notably at the University of Sindh founded in 1947, came to age and aspired to non-manual jobs and an urban lifestyle. When the One Unit scheme, which merged all administrative units of West Pakistan into a single province, was implemented in 1955, the political elite and this new Sindhi-speaking middle-class increasingly felt threatened for the future of their culture and language. Writers and students, who not only feared for the sake of their culture but also for their own career, opposed resistance to the One Unit and to Ayub Khan’s regime. One of the major voices of Sindhi writers and students against One Unit was Rūh Rihān, a literary journal banned twice because of its political stance. As its editor Hamid Sindhi (1939-2012) told me in an interview:

G. M. Sayed’s writings gave a formal and explicit shape to the association of Sufism with Sindhi identity. They inscribed Sufism in a nationalist historical narrative that highlighted the continuous occupation of the lower Indus Valley by one people, the Sindhis, and the constancy of their culture from the days of the Harappan civilization. But if G. M. Sayed is seen as the rahbar, or ‘founder’, by Sindhi nationalists, it could be argued that his books in fact synthesized and condensed the work of a whole generation of Sindhis engaged in a broader process of identity construction during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, that drew on popular culture to craft a set of identity markers. While elected representatives saw their power increasingly curtailed (Tahir 2010, Talbot 1998), a new generation of Sindhi Muslim men educated in Sindh, notably at the University of Sindh founded in 1947, came to age and aspired to non-manual jobs and an urban lifestyle. When the One Unit scheme, which merged all administrative units of West Pakistan into a single province, was implemented in 1955, the political elite and this new Sindhi-speaking middle-class increasingly felt threatened for the future of their culture and language. Writers and students, who not only feared for the sake of their culture but also for their own career, opposed resistance to the One Unit and to Ayub Khan’s regime. One of the major voices of Sindhi writers and students against One Unit was Rūh Rihān, a literary journal banned twice because of its political stance. As its editor Hamid Sindhi (1939-2012) told me in an interview:

[The struggle against One-Unit] was also a struggle for the liberation from the inside. […] You can call it ‘sufiana’, whatever it is… In those days, we all also used to follow these ideas: a Sufism sort of life, as Latif. We loved Latif, why? Because he preached Sufism. […]

We were not complete Sufis, but definitely concerned about our future. The youngsters in our movement were concerned about future because they don’t have the jobs or they don’t have any shelter or cover, so they joined so that we should have a share.

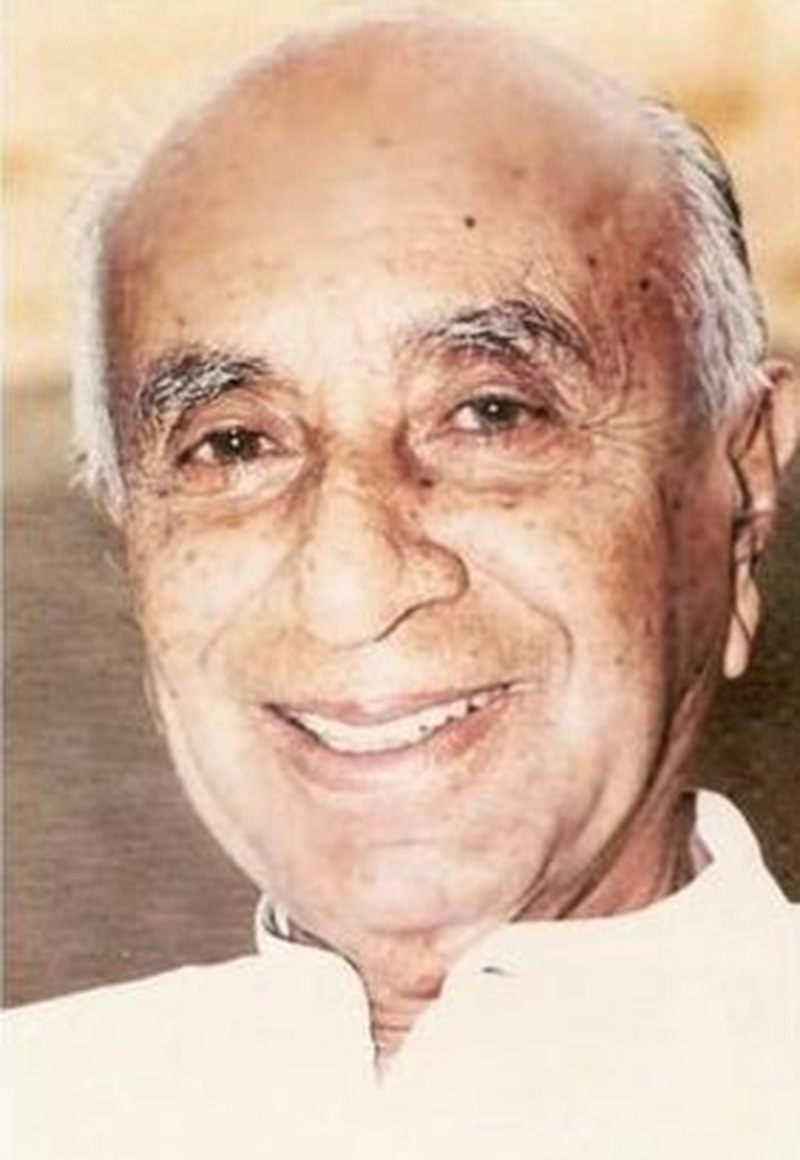

In an interesting twist, Hamid Sindhi conflates his literary and political engagement against One Unit with emancipation – both spiritual and collective, but what appears clearly in these few sentences is that this struggle was also about securing one’s future job. Young Sindhis’ opposition was thus sparked by the perception that Ayub Khan’s modernist economic program didn’t accord much space for Sindhis. In many ways, Hamid Sindhi’s social trajectory reveals the anguish and frustration felt by a generation of young Sindhi students who gained access to higher education but found difficulty in materializing the career they had been promised. Born Abdul Hamid Memon in 1939, he studied law but was mostly active as the editor of Rūh Rihān, a magazine which constituted a bridge between the two groups that were at the forefront of the mobilization against Ayub Khan’s rule in Sindh: writers and students. He joined public service in 1970 and like many Sindhis who had voiced their opposition to One Unit, led a successful career as a government employee when a Sindhi, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, was at the helm of affairs.

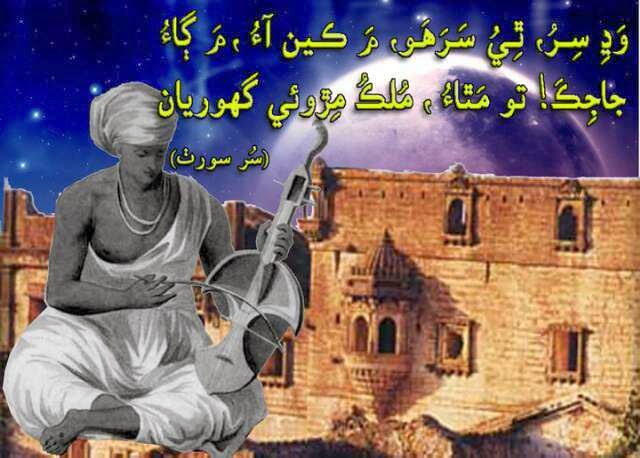

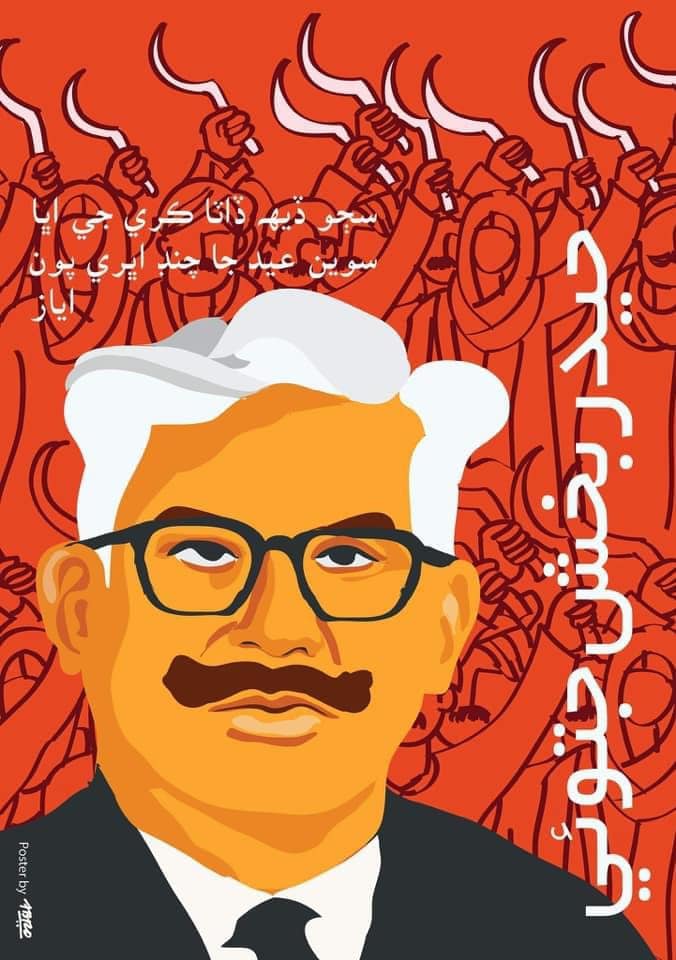

Hamid Sindhi’s Rūh Rihān brought together all the symbols and references used by students and writers, both in their writings and in their mobilization. These tended to depict Sindh as a rural, mystical and peaceful society, characterized by its holy men and heir of the Indus civilization, yet presently at the mercy of its landed elite, urban capitalists and the Pakistani military. This imaginaire of Sindh as a rural, mystical and peaceful society was also nourished by the activity of cultural institutions established after independence: the Sindhi Adabi Board (or Sindhi Literary Board) in 1951, and the Sindhi Academy at the University of Sindh in 1962 which would later become the Institute of Sindhology. These institutions produced extensive documentation on the literature and traditions of Sindh, inspired by colonial ethnography (the name ‘Sindhology’ directly refers to Egyptology or Indology). Drawing on the ‘popular’ as the reservoir of Sindhi culture (Chatterjee 1995), they produced typified categories of people, each with their own myth of origin, dress and traditions, as displayed for instance in recreated village scenes at the Sindh Museum in Hyderabad or in the Lok Virsa Museum in Islamabad. This scholarly, institutional study of Sindh ‘folklorized’ Sindhi culture in that it enshrined traditions, practices and items in a distant rural past, embracing their disappearance at the hands of a more ‘modern’ lifestyle while transcribing oral traditions on paper. The process of folklorization, ‘in which a social group fixes a part of itself in a timeless manner as an anchor for its own distinctiveness’ (Rogers 1998), essentialized the identity of Sindhis, entitling them to a sense of property over specific cultural expressions which then could act as identity markers. Among the identity markers that came to represent Sindh, the reference to Sufi spirituality occupied a prominent place. This appears clearly in an exalted poem by Hyder Bux Jatoi, peasant leader and nationalist, published in 1954 and entitled Salām Sindh (Jatoī 1988). Jatoi mentions three most prominent Sindhi poets, Shah Abdul Latif, Sachal Sarmast (1739-1829), and the Hindu, follower of Advaita Vedanta, Sami (1743-1850), whose words, to many, exemplify Sindh’s ‘Sufi culture’ (Joyo 2009).

Hī sūfian jo des ā, latīf jī zamīn hī;

This is the country of Sufis, the land of Latif;

Hī sāmī wāro āstān, makān-i ‘ārifian hī;

This is Sami’s place, the abode of mystics;

Sachal jo hit darāz āh, sāz āh dīn hī:

Here is Sachal’s dargah, this religion is music:

Hite ā dīn ‘ishq o uns, ā balad amīn hī!

Here, religion is love and affection, the land of peace!

Hit ā bashar birādarī, hite na zāt pāt ā!

Here mankind is our brotherhood; there is no caste system here!

Ae sindh tū mathān sadā salām ā salāt ā!

O Sindh, may prayers and peace always be upon you!

Thus, by the time G. M. Sayed wrote his books and spoke of Sindh’s ‘message of love’, there had been two decades of literary effort, research and political mobilization that highlighted Sindh’s glorious past and created a reified picture of Sindhi society based on typified categories rather than on observation. But this collective imaginary in which Sufism was one the main markers of Sindhi identity was also located in a certain layer of society, among the generation who gained access to higher studies thanks to educational reforms initiated from the 1940s onward. This new Sindhi middle-class aspired to an urban modern lifestyle and felt the need to sacralize through its poetry, short stories and articles a fantasized traditional rural way of life from which it was gradually severing its links.

The following generation, conversely, experienced growing ethnic and sectarian conflicts. During the 1970s, Bhutto gave the Sindhi middle-class what it most wanted: opportunities in the public service. But the period of Zia ul-Haq’s rule curtailed these openings once more. With the development of colleges and universities in Sindh, a greater number of young people, mostly men, found their way into higher education. That is where, for many, they were introduced to G. M. Sayed’s writings, as campuses constituted the bastions of nationalist groups. But the political socialization of this generation of Sindhi students was made through the experience of violence on campuses and on the streets: whereas the previous generation had worked on constructing a reinvented collective imaginary, this new generation was more militant. The leaders that emerged stood out more because of their capacity to rally activists than because of their thoughts and reflections. Often born and raised in villages, these men, like their predecessors, feared for their future – not only their professional future, but also their physical existence, as martial law allowed for strict repression of ethnic movements while ethnic riots and killings exerted a strong polarizing tension in Sindh. Not willing to abandon the freedom gained with higher education, these men often settled in towns after their studies but kept a strong a connection with their village, where they married and left their wife and children. Their expenditures in the city were often borne in part by village relatives or by a rent coming from land produce. This generation had to face the discrepancy between the idealized Sindhi society – rural, mystical, peaceful, and the actual Sindh of the 1980s, marked by violent conflict blamed on Muhajir invasion and Punjabi domination. It is mostly by people of this generation, whose members are today at the head of Sindhi nationalist parties, that I was told repeatedly that ‘Sindhis are Sufi by nature’. G. M. Sayed’s heritage was more than apparent in their intellectual development: when I asked them to elaborate, they systematically equated Sufism with secularism and universalism, echoing G. M. Sayed’s conception of mysticism.

___________________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence. Before joining CSH, Delhi he was Adjunct Associate Professor at EHESS in Paris. As a researcher at CSH, Julien Levesque focuses on South Asian Islam and Muslims from the perspective of political sociology. More precisely, his project is to study the social and political role of sayyids, a group generally described as the elite among the elite of Muslims in South Asia.

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence. Before joining CSH, Delhi he was Adjunct Associate Professor at EHESS in Paris. As a researcher at CSH, Julien Levesque focuses on South Asian Islam and Muslims from the perspective of political sociology. More precisely, his project is to study the social and political role of sayyids, a group generally described as the elite among the elite of Muslims in South Asia.

Courtesy: HAL Archives and CENTER DE SSCIENCES HUMAINES

Click here for Part-I , Part-II