Such a tax would in theory have two main purposes. First, it would disincentivize firms from replacing workers with robots, thereby maintaining human employment.

By Nazarul Islam

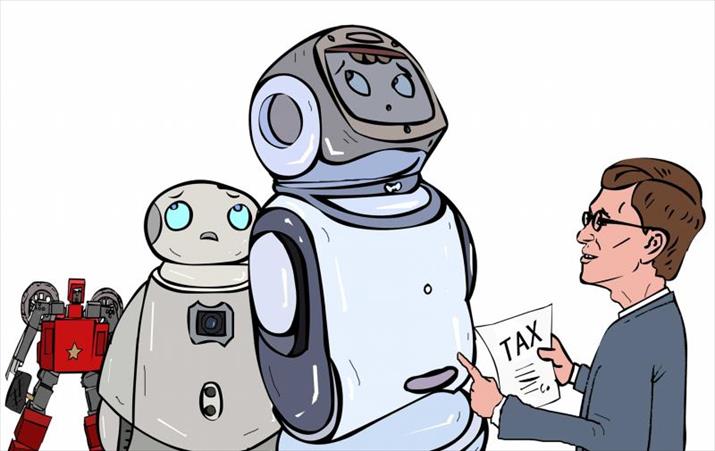

A number of highly regarded business people and politicians, including Microsoft founder Bill Gates and NYC Mayor Bill De Blasio, have commented on the potential need for a “robot tax.” Interest in such a tax appears to be founded on the belief that robots, and automation more generally, will lead to large job losses.

The basic idea behind a robot tax is that firms pay a tax when they replace a human worker with a robot. Such a tax would in theory have two main purposes. First, it would dis-incentivize firms from replacing workers with robots, thereby maintaining human employment.

Second, if the replacement were made anyway, a robot tax would generate revenues for the government that would cover the loss of revenue from payroll taxes. Some proponents of a robot tax also suggest that the revenue could then be used for worker re-training programs or other forms of support for the displaced worker.

While the arguments in favor of a robot tax may be well-intentioned, robot taxes are a misguided idea that would have negative consequences for firms, their workers, and ultimately the economy. To begin with, the assertion that robots are taking jobs is not well founded. Recent research shows that firms that adopt robots experience more employment growth than those that do not.

These firms also appear to be more productive, potentially benefiting consumers, although the gains experienced by the adopting firm may come at the expense of firms that do not adopt. Moreover, defining a “robot” turns out to be non-trivial; depending on this definition, a robot tax may affect some industries more than others, regardless of the impact on human labor.

Ultimately, a robot tax would lead to slower adoption of robots, especially in industries such as manufacturing where it may be easier to define a “robot,” and this slower adoption will likely lead to less economic growth. Instead of robot taxes, policymakers who want to help workers displaced by automation should focus on other policies, such as addressing disparities in taxes on capital and labor and easing labor market frictions. Doing so would benefit workers, firms, and the economy more so than would a tax on robots.

Over the past couple of years there have been several firm-level studies on the effects of robot adoption in industrial settings. These papers all find that firms that adopt robots see an increase in employment. For example, a recent paper by Dixon, Hong, and Wu (2021) uses data on robot imports to identify Canadian firms that adopt robots.

They then compare employment, behavior, and performance between robot-adopting and non-adopting firms. They find that the robot-adopting firms experience a subsequent increase in employment and that the employment increase is predominantly from low-skill workers. As another example, Acemoglu, Lelarge, and Restrepo (2020) find that among French manufacturing firms, those firms that adopted robots add jobs.

A similar finding is in a paper by Koch, Manulov, and Smolka (2019), who use firm level data from Spain.

These studies also find that the firms that adopt robots see an increase in performance (measured as an increase in firm-level total factor productivity or revenue). Interestingly, the studies find that the non-adopting firms in the same industry as the robot adopting firms see decreases in employment. This may be due to reallocation from slower-growing, more poorly-performing firms to faster-growing, better-performing firms.

In some cases, the decreases in employment at the non-adopting firms more than outweigh the employment gains at the robot-adopting firms, causing a location- or industry-wide fall in employment (as shown for example in Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020)).

There have also been papers on robot adoption in service settings. A paper studying the effects of robots on workers in Japanese nursing homes by Eggleston, Lee, and Iizuka (2021) finds that robots complement human labor and reduce labor turnover.

The physically demanding nature of work in nursing homes can often lead to high turnover, so robots in these settings are intentionally designed to assist with the most physically demanding tasks such as lifting patients out of beds. The paper also highlights an interesting feature of the Japanese setting: that many Japanese prefectures provide subsidies for nursing homes that adopt robots. If indeed robots complement human labor, then subsidies make sense and may help spur adoption of robots in these settings.

The evidence from this academic literature has two implications for the idea of a robot tax. First, there is no evidence that robots are directly substituting for human labor—indeed robots may actually be complementing labor, resulting in increases in employment. Taxing firms that are adopting robots may then have the perverse effect of slowing employment growth.

Second, while robots may in part be responsible for some labor reallocation within an industry, the bigger question is what to do about the non-robot adopting firms, since these are the firms experiencing employment decreases. Should these firms be allowed to shrink, perhaps ultimately going out of business, since they are less productive to begin with?

Should there be robot subsidies, so that more firms are able to adopt robots, thereby presumably taking part in employment growth? Also, given the positive performance benefits for firms that adopt robots, why aren’t more firms adopting? Potential reasons could include lack of knowledge about the benefits that robots provide, lack of capital to invest in robots, or lack of skilled human capital at the firm or in the local labor market for adopting firms to hire, among other reasons. These are important questions for researchers and policymakers to study.

One of the challenges with a robot tax is defining what is meant by a “robot.” In a manufacturing context, a robot typically refers to a robotic arm. As defined by ISO 8373, an industrial robot is an “automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulator programmable in three or more axes, which may be either fixed in place or mobile for use in industrial automation applications.”

However, even if we restrict our attention to industrial settings, defining a robot is not so simple. This is one lesson from recent work by Buffington, Miranda, and Seamans (2018). The authors report on the cognitive testing involved in their attempts to define a robot for use in the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of Manufacturers (ASM). The definition ultimately included in that survey explained that robots should encompass machines that can perform the following tasks: palletizing, pick and place, machine tending, material handling, dispensing, welding, and packing/repacking.

Respondents were told to exclude automated guided vehicles (AGVs), driverless forklifts, automatic storage and retrieval systems, and computer numerical control (CNC) equipment. For the purposes of this survey, the inclusion of robotic arms that can do welding and other tasks, and the exclusion of things like driverless forklifts, makes sense given that robotic arms are much more prevalent than driverless forklifts in the manufacturing industry, whereas the reverse is likely true of the warehouse and transport industry.

The exclusion of driverless forklifts from the ASM highlights the difficulty of defining a robot for the purposes of a robot tax. While a driverless forklift may not technically be a robot, as implied by the name it would appear to be an automating technology that substitutes for human workers.

[author title=”Nazarul Islam ” image=”https://sindhcourier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Nazarul-Islam-2.png”]The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his 119 articles.[/author]