Fighting against religious extremism thus stands as one of the priorities of Sindhi nationalist groups.

By Julien Levesque

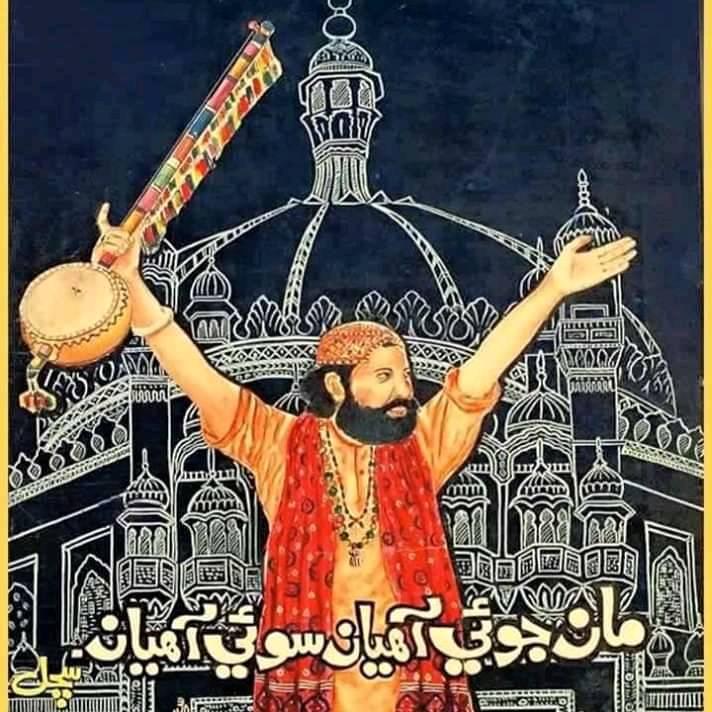

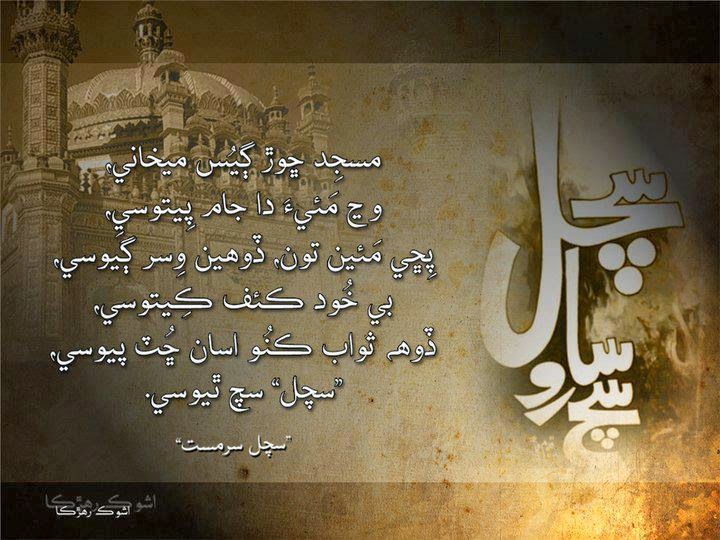

The growth of sectarian violence from the 1980s fueled the perception that Sindh’s ‘Sufi culture’ was threatened by extremist understandings of Islam. Sindhi nationalists like to praise how perceptive G. M. Sayed was when, in a speech made at the Congress of the People for Peace in Vienna in 1952, he advised world powers not to support existing regimes in Muslim countries and warned them of the danger of religious fanaticism. For Sindhi nationalists, the spread of sectarianism and communalism in Sindh is seen as a deliberate strategy by the Pakistani establishment, orchestrated to subdue the province. The various compromises (or outright support) made by the Pakistani state to the demands of religious groups – such as the exclusion of Ahmadis from the status of Muslim in 1974 or Zia ul-Haq’s Islamization policies – are taken as confirmations of G. M. Sayed’s warning. Fighting against religious extremism thus stands as one of the priorities of Sindhi nationalist groups. On the occasion of the ‘Freedom March’ organized in March 2012 by Sindh’s major nationalist party, Jiye Sindh Qaumi Mahaz, its leader, Bashir Khan Qureshi (1959-2012), pinned the responsibility for the spread of sectarianism and extremism on Punjab and Pakistan. But he first placed himself in the lineage of the Sufi tradition of wahdat alwujūd by a direct reference to the tenth century Persian mystic Mansūr Hallāj, hanged for his beliefs:

Arso thio āhe ta mansūr jo āwāz purāno thī vio āhe

For years, Mansur’s voice has seemed distant

Hik bhero warī naīn sar-i dār o rasam khe sīngāran ghurān tho

Once more, let me ornate the scaffold and the rope

After dramatically declaring himself ready for martyrdom, Bashir Qureshi then stated:

Pakistan came into existence as a result of hatred and hypocrisy born out of a wrong conception of religion. This is why its existence has not only been the cause of hatred and destruction for the whole world but has also allowed Punjab to take over the economic, domestic and foreign policy of the country. Thus extremism [intahā pasandī] and a terrorist mentality [dahshatgardī warī soch] have been fanned here, whose victims are not only the whole world and humanity but also Sindh, which, in spite of hosting different religions for centuries, has preserved its tradition of tolerance [ravādārī waro ravāyyo].

Bashir Qureshi thus denounces the sectarianism and extremism that threatens Sindh, the ‘land of Sufis’ which so far had kept its ‘tradition of tolerance’ intact. To illustrate his point, he mentions the forced marriages of young Sindhi Hindu women with Muslim men and takes the example of Rinkle Kumari, whose case was then widely debated in the Pakistani media. After disappearing from her home in Mirpur Mathelo, in northern Sindh, in February 2012, Rinkle Kumari converted to Islam and married a Muslim man in the nearby shrine of Bharchundi Sharif, whose head sajjada nashīn, popularly known as Mian Mitho, happened to be the local elected member of National Assembly, sitting in the ranks of the Pakistan People’s Party majority. Rinkle Kumari’s family maintained that she had been abducted and forcefully married. The case gathered wide media coverage as the Supreme Court of Pakistan stepped in. But Rinkle Kumari’s family, supported by Hindu community organizations and human rights organizations, reproached the Supreme Court not to have investigated whether the conversion was forced or not (Sirmed 2012). Sindhi nationalist parties were among the few political groups that openly supported Rinkle Kumari and the Hindu community. They organized rallies outside the press club of Hyderabad and in Mirpur Mathelo to demand effective protection of religious minorities and request the return of Rinkle Kumari to her family. The case of Rinkle Kumari drew attention to the difficulties of minorities in Pakistan and is symptomatic of what Sindhi nationalists denounce, namely a climate of heightened sectarian and communal division which has led a number of Hindu families from Sindh to leave for India (some speak of the largest wave of Hindu emigration from Sindh since 1948).

A year later, another case of communal conflict brought Sindhi parties to mobilize in support of the Hindu minority. On 8 October 2013, in the southern Sindhi town of Pangrio, the body of Bhuro Bhil, a Hindu man of 28 years who had died in a car accident, was exhumed by a crowd of several hundred Muslim people. Arguing that burying Muslims and Hindus in the same cemetery was contrary to sharia, several people had first warned Bhuro Bhil’s family against laying him to rest in the Haji Faqir graveyard, and finally took upon themselves to unearth the body after the family had gone ahead with the funeral with the support of a local landowner. This event brings together various social dynamics pertaining to caste conflicts – some lower caste Muslims are not allowed either to be buried in some cemeteries – and to land ownership – according to the Herald, those who initially opposed Bhuro Bhil’s burial were part of a group of land grabbers that illegally occupy a part of the graveyard (as it regularly happens in Pakistan).

Yet most of the media coverage of the event highlighted the communal dimension of the affair, which is also what prompted Sindhi nationalist parties, as well as NGOs and advocacy organizations, publicly to take position on the issue by condemning extremism and calling for the unity of all Sindhis, whether Hindu or Muslim. This is what the picture that circulated a few days after the desecration on social media was meant to tell. The picture of Bhuro Bhil’s new tomb on which Jiye Sindh’s flag had been put up carried the following comment:

Yet most of the media coverage of the event highlighted the communal dimension of the affair, which is also what prompted Sindhi nationalist parties, as well as NGOs and advocacy organizations, publicly to take position on the issue by condemning extremism and calling for the unity of all Sindhis, whether Hindu or Muslim. This is what the picture that circulated a few days after the desecration on social media was meant to tell. The picture of Bhuro Bhil’s new tomb on which Jiye Sindh’s flag had been put up carried the following comment:

‘Bhūro Bheel be hik Sindhi……!!!’, ‘Bhuro Bhil is also a Sindhi’. Sindhi nationalist parties also took part in the ‘Long March’ that was organized over three days from Mirpur Khas to Hyderabad. One of the cadres of Jiye Sindh Qaumi Mahaz, Dr Niaz Kalani, joined the meeting at the start of the march and spoke to various TV reporters. Several dozens of activists had come along with him and carried flags of Jiye Sindh, which now stood among the slogans of the event’s organizers like the Bheel Intellectual Forum – ‘mulk men intahā pasandī khe khatam kayo vanjī’, ‘stop extremism in the country’. As in the case of Rinkle Kumari, Bhuro Bhil’s exhumation was taken by many as a symptom of the erosion of Sindh’s ‘Sufi culture’ at the hands of the growing sectarian and communal polarization. On 23 November 2013, on the occasion of the fortieth day of mourning (chahlam), a Sindhi nationalist group convened a ‘Sindh Inter Faith Conference’ for the unity (yakjatī) of Sindhis. It took place in Hyderabad in the suitably named Besant Hall, dedicated to Annie Besant, the president of the Theosophical Society from 1891 to 1933, which so significantly influenced thinkers such as Jethmal Parsram and G. M. Sayed. The party leader, Riaz Chandio, denounced a state ‘conspiracy against Sindh’s Sufi way [mat]’ and praised the Sindhi loyalists (‘halālion’) who realize that ‘Bhuto Bhil is a true son and heir of this soil’.

Sindhi nationalist parties thus see themselves as defenders of Sindh’s ‘Sufi culture’ against a rising extremist and sectarian Islam that, according to them, is diffused with the support of the Pakistani state. But the two events that we related—Rinkle Kumari’s conversion and Bhuro Bhil’s exhumation—in-fact paint a more complex picture. In both cases, those Muslims engaged in communal conflicts are led by religious figures who draw their spiritual authority from the Sufi tradition. In the case of Rinkle Kumari, Mian Mitho and the pīrs of Bharchundi Sharif, an important Qādirī shrine in the northern district of Ghotki, play the central role. The implication of the pīrs and disciples of Bharchundi in various movements for the defense and promotion of Islam is nothing new—and Mian Mitho proudly projects the dargāh of Bharchundi as a center where people come to convert to Islam.

Behind the crowd that exhumed Bhuro Bhil’s body also figures a local cleric who belongs to a Sufi order. Pir Ayub Jan Sarhandi, a naqshbandī mujaddidī pīr and a member of the Barelvi movement Ahl-e Sunnat wa’l Jamaat, was one of the religious leaders who stirred up local tensions. His name appears in various cases of conversions in the 2000s in the Thar region. In April 2008, for instance, he converted in one go 270 Bhil men and women (http://www.dawn.com/news/300339/mirpurkhas-more-than-270-embrace-islam, accessed 16 December 2015). He generally boasts having converted more than 10,000 people to Islam in the course of his life. He is also mentioned in accounts of forced conversions, along a modus operandi very similar to that employed for Rinkle Kumari. Pir Ayub Jan Sarhandi is bitterly opposed to Sindhi nationalists, whom he accuses of being ‘Indian agents’. He denounces G. M. Sayed’s thought as a threat for Sindh, as in this speech pronounced at the ‘urs of Pir Sayed Mahbub Ali Shah in Havelian (Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa):

In Sindh, there are two ideologies. The first is that of G. M. Sayed, an ideology full of violence [mār-dhār], hatred, atheism [ilhād], associatism [shirk], innovation [bid’at]. The second is that of the Naqshbandi tariqa [khwāja-i khwājagān], the everlasting Saint Shah Muhammad alias Ibrahim Jan Faruqi Sarhandi.

______________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence. Before joining CSH, Delhi he was Adjunct Associate Professor at EHESS in Paris. As a researcher at CSH, Julien Levesque focuses on South Asian Islam and Muslims from the perspective of political sociology. More precisely, his project is to study the social and political role of sayyids, a group generally described as the elite among the elite of Muslims in South Asia.

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence. Before joining CSH, Delhi he was Adjunct Associate Professor at EHESS in Paris. As a researcher at CSH, Julien Levesque focuses on South Asian Islam and Muslims from the perspective of political sociology. More precisely, his project is to study the social and political role of sayyids, a group generally described as the elite among the elite of Muslims in South Asia.

Click here for Part-I , Part-II , Part III