“War” and subsequent occupation of Tharparkar in the winters of 1971 is still the most traumatic memory for the now older generation of several Hindu and Muslim communities in Tharparkar.

Sadia Mahmood

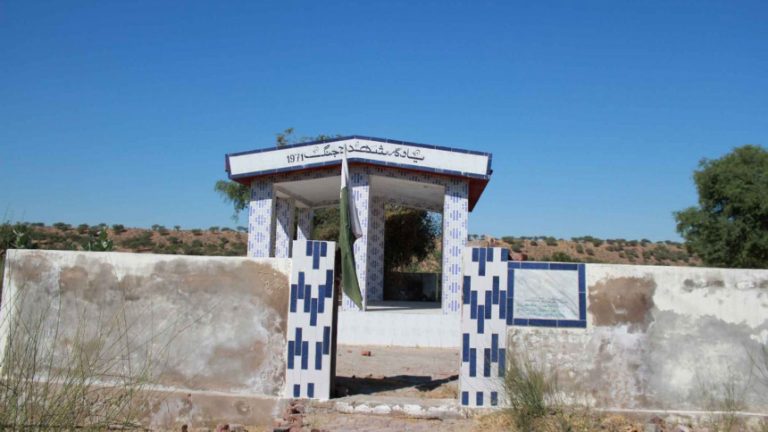

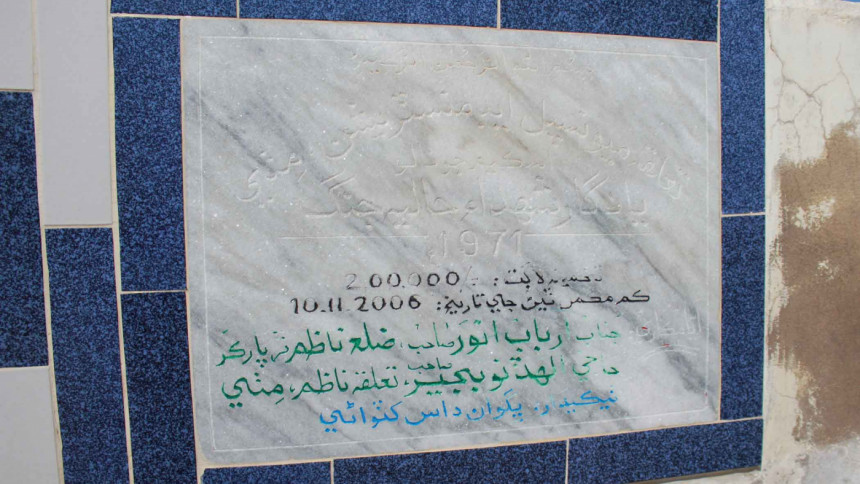

Perhaps the only memorial for the martyrs of the 1971 war in Pakistan stands quietly and forgotten near the village Barach, about 25 kilometers southeast of Mithi, the desert district headquarters of Tharparkar. This Pakistani border district is adjacent to the Indian states of Rajasthan and Gujarat. In 2012, I stumbled upon this memorial accidentally during my Ph.D. field trip to Chachro from Mitthi. I worked with various Hindu communities in Tharparkar then, and they talked a lot about the 1971 war. “What is that?” I asked my host who was driving. “This is yaadgar (a memorial),” came the reply. According to my host, who was Hindu himself, many Pakistani soldiers had died in an accident on this spot in 1971. We stopped to take a closer look. “Who built this?” was the next and a somewhat goofy question on my part. “A Hindu contractor,” came the proud reply. This made me think about 1971 in Tharparkar from a unique angle. Questions such as what the connection of 1971 with Tharparkar is and how did it affect the lives of people in this region swept through my mind. What the significance of Yadgaar-e-Shuhada in the desert is while many in Pakistan do not know or have forgotten about the 1971 war and the occupation of this region by India. Above all, I was thinking about the complex relationship between early Pakistani polity with its Hindu citizens. What could Tharparkar teach us about 1971, the minoritized citizens, and demographic shifts in South Asia?

A Hindu contractor had built the War Memorial near Mithi town of Tharparkar district

To understand the significance of these questions, one must understand the relationship between the post-colonial state and Hindus as well as the complex processes in the making of a unique borderland, Thar. One must also keep the ensuing violence hundreds of miles away in East Pakistan in mind. After the Partition, Pakistan’s founding political party continued its attitude of hostility towards “the Hindu” in Pakistan. The East Pakistani Hindus bore the brunt of this hostility as many prominent and outspoken Pakistani Hindu politicians came from East Pakistan. The continuity of the All India Muslim League’s attitude of distrust towards Hindus was one of the leading factors in silencing the Hindu voices, including those of Schedule Castes in East Pakistan. The loyalty of Hindu politicians was continuously questioned in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan during several foundational debates. They were easy targets of communal accusations and point-scoring by the Muslim Leaguers. During the military operation of 1971 in East Pakistan, Hindu politicians and academics were picked and never returned from custody. Moreover, this border between Pakistan and India was used by Bengalis in Pakistan to exit Pakistan to India on their way to Bangladesh.

“What happened in 1971?” I asked a man in a village the name of which I have forgotten now. “It was not a war,” he replied. “What was it then,” I insisted on knowing. “It was a baghawat (a mutiny) in East Pakistan.” He replied thoughtfully. “Then what happened here in 1971?” “India attacked – there was no fight here,” he continued telling me. “War” and subsequent occupation of Tharparkar in the winters of 1971 is still the most traumatic memory for the now older generation of several Hindu and Muslim communities in Tharparkar.

Although the oral accounts do not mention any conventional warfare but just the encounters with this army or that, or looting of household items by the Indian army. 1971 in this border district allows us unique insights into the Partition of 1947, the third Indo-Pak war, also known as Bangladesh’s War of Liberation of 1971 and 1971 in Tharparkar. One thing that makes Tharparkar stand out from other borderlands in the region is that it has maintained a visible presence of Hindu communities unlike other regions in Pakistan. Some of the local castes such as Sodhas and Pushkarnas are now trans-national and live in a region that is a borderland between Pakistan and India. Both Pakistan and India have had two military conflicts in the region. After the clashes of 1965 and 1971 this border region became heavily militarized and even after all this traumatic past, Tharparkar refuses to evict its Hindus.

Whereas the international boundary drawn in 1947 is known as leeko (Dhatki, line), dang (the limit), or simply border, the 1971 war and occupation of Tharparkar is referred to as Ekhatar wari Jang (the war of 71). For Tharis, 1947 wasn’t a life-changing event; people came via the border town of Gadro and left for Karachi or other larger towns of Pakistan. Tharparkar remained insignificant as it had no opportunities to offer to the refugees. The questions of nationality and citizenship of the nascent Islamic nation didn’t bother the Hindus in Tharparkar. This, however, doesn’t mean that issues stemming from the Partition were non-existent in Tharparkar.

Whereas the international boundary drawn in 1947 is known as leeko (Dhatki, line), dang (the limit), or simply border, the 1971 war and occupation of Tharparkar is referred to as Ekhatar wari Jang (the war of 71). For Tharis, 1947 wasn’t a life-changing event; people came via the border town of Gadro and left for Karachi or other larger towns of Pakistan. Tharparkar remained insignificant as it had no opportunities to offer to the refugees. The questions of nationality and citizenship of the nascent Islamic nation didn’t bother the Hindus in Tharparkar. This, however, doesn’t mean that issues stemming from the Partition were non-existent in Tharparkar.

The demography of this region, historically part of Rajasthan, changed only slightly in 1947. The border remained porous, allowing the local people to continue their relations on both sides of the border with minimal restrictions till the 1965 Indo-Pak war. Local people mention that, in the case of a wedding procession to Rajasthan, before the 1965 war, they were required only to inform the in-charge at the check post about where they were heading and with how many people. No travel documents were required. The border was sealed gradually, with the final stroke in 1971. A vast area of Tharparkar went under Indian occupation in December of 1971. The Indian army attacked this sector to mount pressure on Pakistan in connection with the war in East Pakistan. It remained under Indian occupation until the Indian forces departed Tharparkar after the signing of the Simla Pact in 1972. This formally ended the 1971 India Pakistan war; the governments of India and Pakistan reached an agreement for the release of POWs and the return of occupied territory and civilians in Tharparkar.

Chahchro was then a small town. Located approximately 50 kilometers from the Pakistan-India international border, it was entirely abandoned in 1971 after the Indian occupation. The Indian advance into this sector, occupying Nagar and Chachro, two main sub-divisions in the region, was sudden. Only four Hindu Chachroites of Khatri caste stayed back, refusing to move into refugee camps in India when asked by the Indian soldiers to come along with them. Even though there was no fight for the control of the city, Chachro can serve as a living war museum as the unlooked-after mud walls and in some places, only the wooden doors, with no walls present a stark contrast to the newly built cemented houses. Chachro was the hometown of Rana Lachman Singh, the Rana of Chachro. A year before the war, in 1970, Rana Lachman Singh departed Chahchro secretly in the night for India after a humiliating spat with a local officer. Tharparkar of the 1970s can be best described as living in the age of camels and kekras (six-wheeled army trucks). Rana Lachman Singh’s family in India, whom I contacted through Facebook and via email, also refused to narrate the events to me that led Lachman Singh out of Chachro. The mansion of Rana, a pink Kotri, can be recognized from far as it is a prominent building. No one lives in the Kotri now because one just cannot start living in someone’s house, I was told. There are caretakers and the Kotri has been renovated as a guest house. The caretakers hardly spoke to me but did extend warm traditional hospitality.

Rajputs in Tharparkar view themselves as having been transformed into a minority after 1971, as their numbers and power declined in the region after the war. Local people have transformed Rana Lachman Singh into a mythical character. The narrative of his departure from Chahchro is enhanced by rumors of his return with the Indian army in December 1971.

When the Indian occupation ended, a large number of Sodha Rajputs opted to remain in India (they had already moved to the camps established by the Indian government, Some Muslim castes now locally known as Muhajirs also moved to Tharparkar from Barmer and Gujarat in 1972.) This was a huge decision to change their citizenship 24 years after the Partition. In the case of Sodhas of Tharparkar, it was 1971 and not 1947 that turned them into a minority in Pakistan. The Sodhas were the landed elites of Tharparkar, and they faced the pressure of refugees seeking ‘evacuee property’ after 1947. They ended their transitory status in the 70s when they decided not to return to Pakistan. They were sent a message by their community leaders: Diwali doesn’t occur daily. However, many other Hindu communities did return when the Pakistani premier, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, sent a delegation of three members to bring the Thari Hindu refugees back to Tharparkar. According to National Assembly records, an estimated 55,000 people returned to their homes. The Enemy Property Act of 1965 was extended to Tharparkar and the property left behind by the people who decided not to return was declared Enemy property. The title, Enemy Property, makes the relatives that stayed in Pakistan emotional to talk about the losses this war incurred upon them.

However, switching countries didn’t solve citizenship problems for the Sodhas. The locals who have relatives on either side of the border told me about the difficulties they face in visiting their relatives. To get an Indian visa, they must travel to Islamabad, which is quite a journey from Tharparkar. Sodhas still marry their daughters to Jadejas, a sub-caste of Rajputs now living in India. Until the first military conflict in the region, it was easy for the community to maintain matrimonial relationships and frequent family visits on the other side of the border. However, the conflict over the border in the Rann of Kutch area between the two post-colonial states, as well as smuggling and human trafficking, increased the surveillance of the border beginning in the 1960s. After the 1965 and 1971 conflicts between the two nation-states led to the militarization of the border in the region, resulting in a definite blow to community affairs, especially affecting the lives of Sodha women. Pakistani Sodhas, due to border and visa restrictions, cannot keep track of their daughters’ lives in India and complain that many women are abandoned by their Jadeja in-laws after their dowry has been confiscated. Two films, Mehreen Jabbar’s Ram Chand Pakistani (2008) and Ashvin Kumar’s short film Little Terrorist (2004) show the impacts of geopolitics and nationalism on the lives of people living in this borderland. These films highlight the issues of belonging, citizenship of border communities.

Tharparkar was and still is a very fluid region, despite having remained on the periphery of the nation state for decades. If we borrow Sarah Ansari’s paraphrasing of Ludden, ‘when fluid processes, rather than, fixed structures, become our object of study, apparent peripheries…are transformed into crucial cites for historical exploration’, Tharparkar offers us a unique window of exploring many questions related to identity, citizenship, nationality, religious nationalism and importantly, caste in this borderland related to the Partitions of 1947 and 1971 and above all shows us how human beings and states respond to events in the times of cataclysmic upheaval. “Hindus” were considered the fifth column in Pakistan since its inception. They were found behind every conspiracy leading to the break-up of East Pakistan. But in the case of Tharparkar, not only did Bhutto bring Pakistani Hindu citizens back from India but also made a firm alliance with the Rana of Umarkot and chose him to be part of his cabinet after 1971. It was not only the Partition of 1947 that led to the demographic changes in South Asia, but The Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971 also played a role in coercing the citizens on both sides of the border to choose the right country for them.

____________________

Dr. Sadia Mahmood is Assistant Professor at Quaid-e-Azam University, Pakistan.

Courtesy: The Daily Star (Published on March 28, 2021)