The presence of living creatures, from the animal worlds, began in poetry from ancient times

By Ashraf Aboul-Yazid, Egypt

President, Asia Journalist Association, Korea

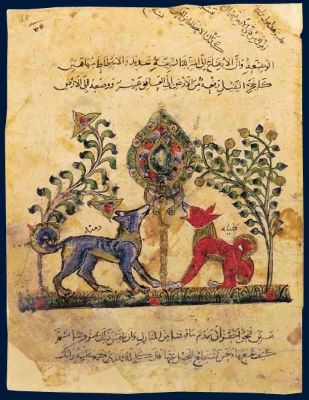

My paper examines how the inclusion of objects in poetry and literature has evolved over the ages, revealing their symbolic and thematic equivalents. There is no doubt that, in Arabic literature, we mention that the first example that embodies the presence of animals in written texts comes through the book Kalila and Dimna, and coincidentally, it is a translated text, signed by Abdullah bin Al-Muqaffa, which came through his translation into Arabic in the eighth century of the Indian book Panjatantra, which dates back to approximately the year 300 AD.

Global Examples

Evoking creatures was necessary to understand the environment, so that the animal became a symbolic equivalent of the human being in it. We have seen this in contemporary world literature; Leo Tolstoy “humanized” the horse and gave it human characteristics in his story “A Horse with a Human Head.”

As for the “Behemoth” cat in the novel “The Master and Margarita by the Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov, it was one of the most charming cats in Russian literature, and there is “Ruslan and Ludmila “; a poem by Alexander Pushkin, published in 1820.In this and that, cats represented a symbol of wisdom and cunning, just as other animals, such as dogs, symbolized dedication and selflessness.

In his poem “Platero and Me,” the Spaniard Juan Ramón Jiménez speaks in a poetic way about the life and death of the donkey “Platero,” which was used as a symbol of the incidents and stories taking place in his village that emanate scents of sadness and nostalgia. The book, as described, is not a history of the life of a talkative donkey, but rather a close symbol. From the heart of its owner, more than from the human being whom Jiménez portrays as a being without feelings and without a soul.

The animal became a symbolic equivalent of the human being. We have seen this in contemporary world literature.

As for the novel “Don Quixote” by Cervantes, its hero is the caricature character Alonso Quijano, who has lost his mind due to the many stories of chivalry he has read. He leaves his home, his customs, and his traditions and travels as a chivalrous knight from the Middle Ages, on an adventurous journey in search of glory, where he decides to arm himself with ancient armor. He wears a worn-out helmet with his weak horse, “Rocinante,” in search of correcting the mistakes committed by others. His role is to help the marginalized, the deprived, and the poor, repeating through this role the role of wandering knights.

As for the most famous contemporary Western models, we find them in the novel “Animal Farm” by George Orwell, whose events take place on one of the farms in England, where the pig collects the animals in the barn, assuring them that the misery that haunts them is caused by man, and they must get rid of the rule of this tyrant. This revolutionary pig dies. Days after delivering his speech, his words and slogans continued to incite other animals to revolt against their enslaved man, so they raised slogans such as “The six-word sentence ‘four legs good, two legs bad’,” and all animals are equal.

Here, Mr. Jones, the owner of the farm, attacks the rebellious animals, but he fails miserably, as they have turned Farm to farm is owned by animals, not humans. Over time, pigs became dominant, ruling without elections, rejecting all objections, and even beginning to resemble humans in this reprehensible behavior.

Referred to “Animal Farm”, we may recall a novel by the writer Jamal Matar (United Arab Emirates), entitled “Spring of the Jungle,” in which he raises many important human issues such as power, influence, loyalty, and cunning in a new and different way, with a theatrical sense and a poetic breath, for the heroes of the novel who are forest animals, presented by the writer. Through a distinct dramatic plot in the story of a smart mouse that was chosen to replace the lion in ruling the forest during his absence, he tried, with his cunning, to overturn the forest system to achieve his personal interests.

In (The Heart of a Dog), the Russian novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, the dog, the hero of the novel, is transformed into a human being after a pituitary gland imported from a human being was implanted in him. Such symbolic projections were clear in its critical references to Russian society. It has been described as a bold, creative work… that distinguishes between the learned and the ignorant, between the producer and the consumer, and urges every human being to take his rightful place.

As for the story The Story of a Seagull and the Cat Who Taught Her to Fly by the Chilean writer Luis Sepúlveda introduces us to worlds of amazing irony, starting with the title, and passing by its author’s indication that it is “a novel for boys from eight to eighty-eight,” and it tells the story of the cat “Thorbas,” who suffered greatly in teaching the little seagull “Lucky” to fly. What is amazing about the novel is the magic effort that the author put into weaving dialogues between (animals – characters) in the novel, which was described as teaching people brotherhood, cooperation, and persistence.

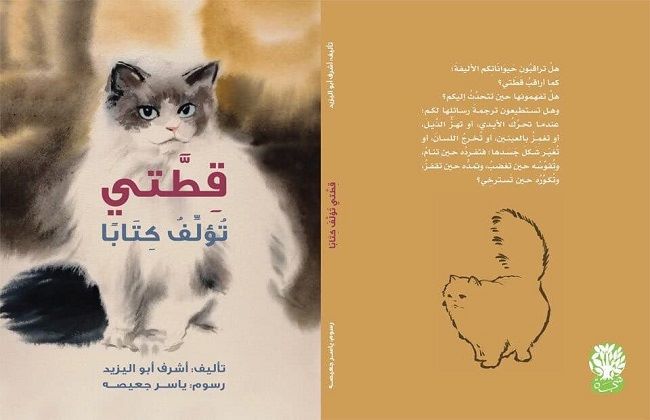

My novel for young people (My Cat Is Writing a Book) presents in the language of science how a cat can chronicle her adventures, and speak in the language of humans to give them advice on how to treat her pets.

In Chekhov’s masterpiece “Pain,” there is an old peasant who carried his sick wife in the back seat of the cart drawn by a frail horse, to the distant city to treat her, and he soothes himself and consoles his sick wife, who lived with him for about 40 years in misery, misery, and suffering, and here he feels… By being negligent towards her, and how cruel he was towards her; He must now compensate her with kindness, gentleness, and kind words. He continued talking and reached the city, and his wife had died, before she had time to hear his sweet words. What is important in the story are the striking references that intersperse its events and describe the torments of the horse pulling the cart. He was that miserable animal that was crawling slowly, dragging its feet in the snow very weakly.

Arabic Treatments

The presence of living creatures, from the animal worlds, began in poetry from ancient times, and then the humanization of animals came to embody human images, meaning the borrowed beauty of women as in the eyes of the oryx, and the courage of men from the lion.

We find, for example, that the oryx in Arabic poetry has images whose elements are repeated. Poets usually begin to depict the male oryx (wild bull) by likening it to a she-camel, and then they proceed to depict it however they want. They describe its appearance, its movement, and then its struggle with (the hunting dogs) in the morning. The poet pays attention to the blackness of its legs, its face, the whiteness of its back, and the kohl of its eyes.

These features of the external appearance may have a symbolic value for the poet, related to the bull’s legendary relationship with the sacred moon, to the point that the moon was known as the bull, but the other side of the image – which is the psychological aspect, represented by: the bull’s anxiety and isolation – seems to predominate in the image.

Perhaps this represents the camel’s anxiety, or rather the anxiety of its owner. Because the wild bull in its stereotypical pre-Islamic image can be seen as a symbolism for a man (or masculinity) connected to the moon, just as it can be seen in (the abyss) a symbolism for a woman (or femininity) connected to the (sun).

Hence, it is clear that the entrance to understanding the aesthetics of the image in Arabic verses, and those similar to them about (the wild bull), must be mythological. Because that is one of the foundations – if not the foundation – on which the poet built the aesthetics of the image:

Tomorrow is like an angry friend, its board is shaking

Of emancipation, had it not been for him,

I wish you would have been destroyed

He is terrified by terrors without worrying him.

The prudent shepherd also worshiped the sheep

He is a young bull, as if he were the Suhail Star, who spends the night content with what little provision he had. He continues to suffer in the sand, when a fire was lit when the rain stopped, a cessation that he identifies in “The Death of the Dew.” Then he (the bull) becomes like a luminous sword, terrorized by terrors without worrying him.

It is an image that gains the reader’s sympathy and admiration. That spirit of humanization emanating from the symbolic dimension represented by the “wild bull” in the poet’s imagination. So that he showed us the image of a human being, with all its sensory and moral beauties: young, powerful like the star (Suhail) on the mountain , content, struggling, not defeated by adversity, continuing on his path, like a sword, or like a camel stallion, despite the horrors around him. . Moral and social values control the aesthetics of the image here violently and effectively. Because the image must ultimately be appropriate for the person it symbolizes

The pre-Islamic person – or the man in particular – is the “flying bird” that is meant in such an image, as he does not settle in a place, but is a traveler in search of water and pasture, except that he is like a tent, caring for his family. Just as he depicts the symbol of the woman (the sun) by saying: The sun has causes as if its rays, stretching ropes in a covered tent.

Thus, the aesthetics of the pre-Islamic man – with his appearance of: whiteness and youth, and with his character of: chivalry, struggle, contentment, fatherhood, vulgarity, and other of his aesthetic standards among the Arabs – appear in the image of (the wild bull), which confirms the importance of that image in its symbolism to him. In pre-Islamic poetry, as manifested in these models.

The Wolf’s Concerto

But one animal had a greater presence in Arabic poetry, which was the wolf. Despite the wolves that threatened the Arab and his wealth, poets saw aesthetics in this animal that they admired, so they depicted wolves in their poetry. He also sometimes added to it or gave it some of his human emotions.

The presence of the wolf has become evident in Arabic literature, and we must not forget that many literary titles are named after it, such as the novel “How to Breastfeed a Wolf without It Bites You,” by Amara Al-Khous, and the collection “A Time to Humanize the Wolf,” published in 2014 by the Palestinian poet Ahmed Saadi.

Although they describe the wolf as treacherous – which is a reprehensible characteristic – the poets, even when describing its treachery, do not hide their admiration for its lightness, boldness, strictness, patience, and practice. These are values whose rootedness in the character of the Arabs and their ideals had the effect of admiring them in the wolf, to the point that one of them liked to be called a wolf, or described as a wolf, which prompted their poets to depict the aesthetics of those ideals and values through the wolf.

In addition to the nature of the Arabs, which is keen on courage and heroism that led them to glorify wolves, in whatever form they were, even if they came from their most ardent enemies. It is the idea itself that appeals to Arabs, regardless of its source or its victims.

Even the Bedouin who saw the wolf in the morning eating his sheep will write verses eulogizing his sheep but they will not devoid a spark of admiration for the wolf’s movement:

He (the wolf) claimed a rose (name of his sheep), Umm al-Ward (its nickname), with honey from wolves as they departed early. It is as if a wolf, when he gallops upon my sheep in the morning, is seeking a tendon, but he finds it.

When we consider the aesthetics of the depiction of the wolf in Arabic poetry, some common aesthetic standards become clear among poets in their depiction of the wolf: in its color, movement, and all of its forms. And also in: the sharpness of its nature, its determination, its cunning, its patience, the intensity of its dexterity, its resourcefulness, its rebellion, and other qualities, some of which they admired, so they were inspired by him in drawing their pictures, inspired by him to express Arab ideals and values.

I will stop at a text written by a contemporary Syrian poet Hani Nadeem, who made his book (The Wolf’s Concerto) a mixture of biography and poetry together. He writes under the title: The Hymn of Death and the Destruction of Homes, Finding the Body.

His introduction is: “On the protection of Hamdan al-Zarwal, the most powerful killer of the wolf, the stepson of the donkey.”, and the king of the lyrics of unknown lineage. Nomads and shepherds depend on wolves to know the conditions of the country and the people, so they interpret their sounds and understand their ramifications.

Hamdan Al-Zarwal swore a proud oath that before the cursed war and the mass death in Syria, free and paid, wolves migrated in masses, accompanied by terrifying crying that rent the stomach of the donkey and frightened the cracks of the cliffs.

He said: They write poetry with their voices. They are mostly prose poems, prose interspersed with vocal hymns in the rings. The necessity of soil, the prestige of meaning, and their long legacy of difference…

Al-Zarwal confirmed in his hoarse voice, rising from the position of “Al-Bayyat” melody and ending in “Al-Kurds” melody that they – that is, the wolves – were leaving the houses one by one and separating between sound and sound as if they were “reproaching” and blaming the people before injustice occurred to them or to them.

Hamdan Al-Zarwal wiped the curtain of the tent with his eyes, which resembled the eyes of wolves from looking at them a lot, then he put his hand on my shoulder and said: You will not find a single wolf in all the flocks today, they are all gone… Then listen! This tent is crying… it completely understands what I’m saying!

Al-Zarwal was silent and listened to the crackling of the tent’s twisted wool in this cold night. He said as he turned off the lamp:

Sleep and don’t think too much… If the wolves return, Syria will return!

The wolf is in you all

So go without your shadow

no..

People like you have no confidence, and people agree that their life is a wolf

In killing you

I grew up early

As befits a lone wolf

The antelope left him

I walked on my regret…and my fear walked with me

And fear is fleeting

I knew everything

But I, like people, make mistakes

And I forgot everything after that except the dead!

Whenever I said they were gone..

They carried baskets of their laughter

And they came.”

The Virtues of Dogs

In contrast to the rebellious image of the wolf, comes the image of the dog! Even in the most famous works of the fourth century, which was a book by the scholar Al-Jahiz, bearing the title of Kitāb al-Ḥayawān (The Animal), he will be mixing- in its chapters – between man in his phases and animals in their lives.

He wrote, for example, under the title: Among the signs of the generosity of a dog: And among the signs that the extent of the dog is the abundance of what happens on people’s tongues of praising him with good and evil, praise and blame, to the point that he is mentioned in the Qur’an once with praise and once with blame, and similarly in the hadith, as well as in poetry and proverbs, to the point that it was used in derivations and was used in the way of omens, and in mentioning visions and dreams, and with the jinn, camels, wild beasts, and animals.

You condemned dogs for evil, for shortcomings, for meanness, and for failure, because all of that has been said about them. For what has been said of goodness is greater and of praiseworthy qualities is more famous, and nothing is more comprehensive of the qualities of deficiency than lethargy, because those qualities that are contrary to that give insight and are given as much remembrance as what is mentioned of that and just as the qualities are not the same. What inherits inactivity is inherited by intelligence, and so are the qualities of intelligence in avoiding idleness, because the blameworthy is better than the inactive.

The funniest thing I conclude with is a book entitled (The Virtues of Dogs Over Many Who Wear Clothes), in which the scholar Abu Bakr bin Khalaf Al-Marzuban brings together a selection of quotes, tales and folklore about the virtues of dogs dating back to the tenth century in an enjoyable journey.

Originally written in response to a friendly challenge to demonstrate the moral decline of humanity, the book begins with a lament for the virtuous people who came before who only left their place for all the vile. The main charges against humanity are hypocrisy and insincerity: human beings today are merely “people-like people” and not real people capable of real affection. Sin has a recurring melancholic quality that extends and refocuses the formulaic lament for past loss with which poems of the period repeatedly begin. The dichotomy between the authentic interior and the fragmented exterior turns out to be a peculiarity of humans; while animals are incapable of feigning emotion (deceptive creatures like foxes are the exception rather than the rule).

The dog, for example, embodies internal and external collapse. All of this is an authentic surface. The dog protects its owner, is loyal in hunting and guarding, watches over one’s property, and by barking in response to cries for help, guides those who are lost to safety. Heroic dogs are rewarded for their loyalty and self-sacrifice with human privileges: many are allowed into domestic spaces that would normally be off-limits to others.

It is difficult to praise a dog in a society whose culture was ambivalent toward dogs at best, and where Islamic discourses on the nature and function of dogs represent a set of tensions related to the roles of history, mythology, rationality, and modernity in Islam. In fact, debates over the declared impurity of dogs, and the legality of owning or living with these animals, were major issues symbolizing the dynamic of challenge between revealed religious law and the state of creation or nature. In addition, certain aspects of these debates relate to patriarchal power dynamics and, more generally, the construction of social attitudes towards marginal elements of society.

Similar to medieval European folklore, black dogs in particular were seen as ominous in Islamic tradition. According to a tradition attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, may God bless him and grant him peace; black dogs are evil, or devils, in animal form. This reflects part of pre-Islamic Arab mythology, but it had limited influence on Islamic law.

Prophet’s wife Aisha, strongly protested symbolic association between dogs and women because of its degrading effects on women.

The vast majority of Muslim jurists considered this particular tradition to be wrongly attributed to the Prophet, and therefore apocryphal. However, much Islamic discourse has focused on a prophetic narration stating that if a dog, regardless of color, licks a bowl, the bowl must be washed seven times. The main point conveyed by these narrations is that dogs are impure animals, or at least that their saliva a pollutant voids the purity of a Muslim.

Hostility to dogs, not only as a source of physical but moral impurity, is further expressed in prophetic accounts claiming that angels, as agents of God’s mercy and forgiveness, will not enter a home with a dog, and cultural bias against dogs as a source of moral danger reaches an extreme point in reports which claims that the Prophet ordered Muslims not to trade or deal in dogs, and even to slaughter all dogs, except for those used for grazing, farming, or hunting.

These different anti-dog narratives present culturally ingrained social concerns about aspects of nature that were seen as threatening or unpredictable. In addition, discourses about dogs played a symbolic role in attempts by pre-modern societies to explore the boundaries that distinguished humans from animals.

In this sense, discussions about dogs served as a forum for negotiating not only the nature of dogs but also the nature of humans. This is evident in traditions that create a symbolic bond between marginalized elements of society, such as non-Muslims or women, and dogs. In some of these hadiths, the Prophet, may God bless him and grant him peace, is alleged to have said that if dogs, donkeys, women, and in some accounts non-Muslims pass in front of men in prayer, they invalidate or invalidate that prayer.

Interestingly, early Islamic authorities, such as the Prophet’s wife Aisha, strongly protested this symbolic association between dogs and women because of its degrading effects on women. As a result, most Muslim jurists considered this tradition incorrect, and that women crossing in front of men does not negate their prayer.

Although the Prophet attributes a large number of anti-dog hadiths, for a variety of reasons, several modern Muslim scholars have challenged this approach. The Qur’an, the heavenly book of Islam, does not condemn dogs as impure or evil. In addition, a large number of early narratives, perhaps reflecting historical practices, contradict anti-dog traditions.

For example, several hadiths indicate that the Prophet’s younger cousins and some of the companions owned young dogs. Other hadiths referred to the presence of him, may God bless him and grant him peace, while a dog was playing nearby. In addition, there is ample historical evidence that dogs roamed freely in Medina and even entered the Prophet’s Mosque. A narration attributed to the Prophet confirms that a sinful woman secured her place in Paradise by saving the life of a dog dying of thirst in the desert.

Most jurists rejected the tradition of killing dogs as fabrications, because they saw such behavior as wasting life. These jurists argued that there was a presumption prohibiting the destruction of nature and requiring honoring of all creation. No part of creation or nature can be destroyed unnecessarily, and no life can be taken without compelling reason. For the vast majority of jurists, since the consumption of dogs is strictly prohibited in Islam, there was no reason to slaughter dogs.

A large number of jurists have permitted the ownership of dogs for the purpose of meeting human needs

Aside from the issue of killing dogs, Muslim jurists differed regarding the permissibility of owning dogs. A large number of jurists have permitted the ownership of dogs for the purpose of meeting human needs, such as herding, agriculture, hunting, or protection. They also banned dog ownership for trivial reasons, such as enjoyment of their appearance or a desire to show off.

Thus, between the treachery of the wolf that poets sang about, and the loyalty of the dog that society hesitated to accept, the dialectic of the animal’s presence in Arabic literature appears. This dialectic inspires writers throughout the ages, whether inspiration is based on mythology, history, or religious literature.

______________

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is an eminent poet, novelist, travelogue writer of Egypt who has authored over three dozen books. His poetry has been translated into over a dozen languages. He is Editor-in-Chief of Silk Road Literature Series.

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is an eminent poet, novelist, travelogue writer of Egypt who has authored over three dozen books. His poetry has been translated into over a dozen languages. He is Editor-in-Chief of Silk Road Literature Series.

[…] Read: The Dialectic of the animal’s presence in Arabic literature | Poetry as an Example […]