Monica’s grandfather was the first in their family to go to Gibraltar. In those days, the men of their community left in shiploads and most of them were employed by Sindhis to work in their overseas shops.

Introduction

Monica Mahtani Bhojwani was born in a prisoner of war camp in France on November 22, 1940, and passed away on March 4, 2020 at the age of 79. She had an exciting story documented in her first book. Monica grew up in post-Partition Karachi. As a young bride, she moved to Gibraltar, where she and her husband Santu lived for ten years. After the subsequent twenty-five years in Las Palmas, they settled in USA to be near their children. Monica, who was never a typical Bhaiband woman, saw herself as an American Bhaiband. When she was young, she rebelled a little against forced traditions and found her own way of processing what she believed in and what she didn’t.

In this historically authentic account of some important events of her life, we get a sense of what it was like for the Bhaiband women of Sindh.

Monica’s story

I was born in captivity, in 1940, in a French town called Royan which was under German occupation during the Second World War. My parents, Rukmani and Hotu Mahtani, set out from Gibraltar where our family had businesses, expecting to arrive in Karachi in fifteen days. Just a few hours short of Colombo, however, their ship, SS Kemmendine, was torpedoed by a German Raider, Atlantis and sank. The passengers who survived were taken as prisoners of war. The story of the weeks they spent on board the Atlantis and then the Norwegian cargo ship SS Tiranna, eventually being miraculously rescued when Tiranna sank and they were taken into a prison camp in Bordeaux, and of their lives in captivity, is written in this book.

The Sindhworki way of life

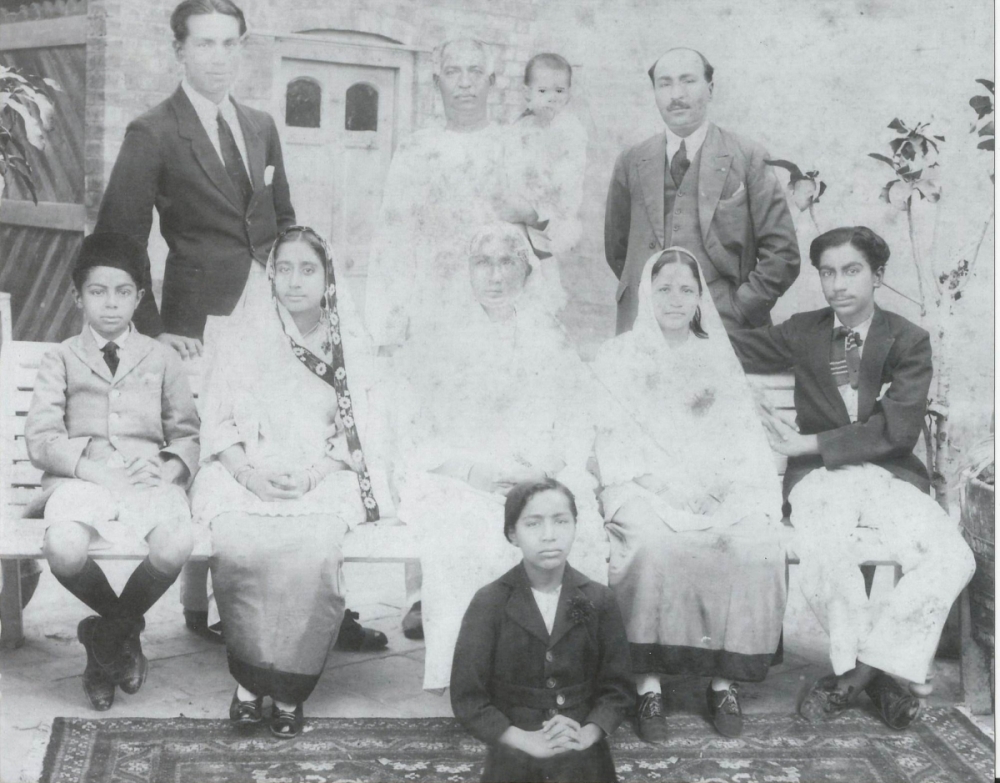

My grandfather, Khemchand Naumal Mahtani, was one of the early Sindhi traders, the Sindhworkis, who established their businesses in North Africa, Western Europe and South America. They left Sindh to trade and set up their shops and started business wherever they found it lucrative. My grandfather made his fortune and came back to live in the family hometown Hyderabad, handing over the business to his sons. Now a wealthy man, he lived a comfortable life and devoted himself to the Theosophy movement, as did many of the intellectuals of Sindh in those days. But my grandmother, perhaps still bearing the scars of their days of struggle and poverty, continued to scrimp and save and resented his magnanimity and philanthropy. Whatever he earned, he would generously give away to his sisters and to anyone who needed help. My grandmother, on the other hand, was very materialistic.

My grandfather was the first in our family to go to Gibraltar. In those days, the men of our community left in shiploads and most of them were employed by Sindhis to work in their overseas shops. They went on a Sindhwork contract for three years and were not allowed to take their wives. After three years they came back to Hyderabad and spent time at home—sometimes six months, sometimes a year, depending on their contract with the firm they were working for. It was generally considered that the women could not go along with their husbands because it was a tough life for a Sindhi women and children out there. It was cold and basically a life for English servicemen and their families who were used to living on their own. Our women, having always lived a protected, cocooned life, would not be able to survive there. Besides, the daughters-in-law back home needed to be with their in-laws to take care of the elders. I suppose my grandmother lived with her mother-in-law in a joint family with her sisters-in-law and their children. Every few years my grandfather would come home and spend a few months. Four sons were born to them: Mangharam, Partaprai, Hotu and Daulatram.

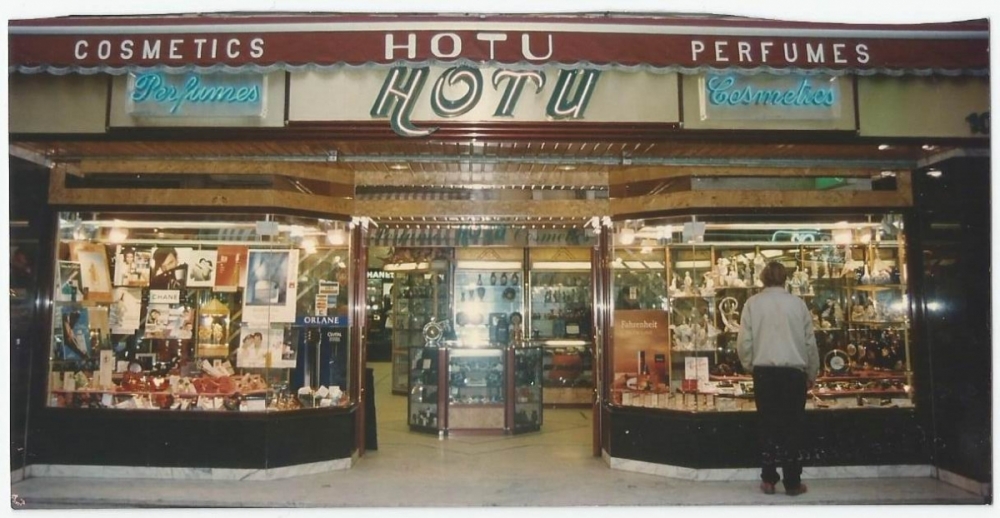

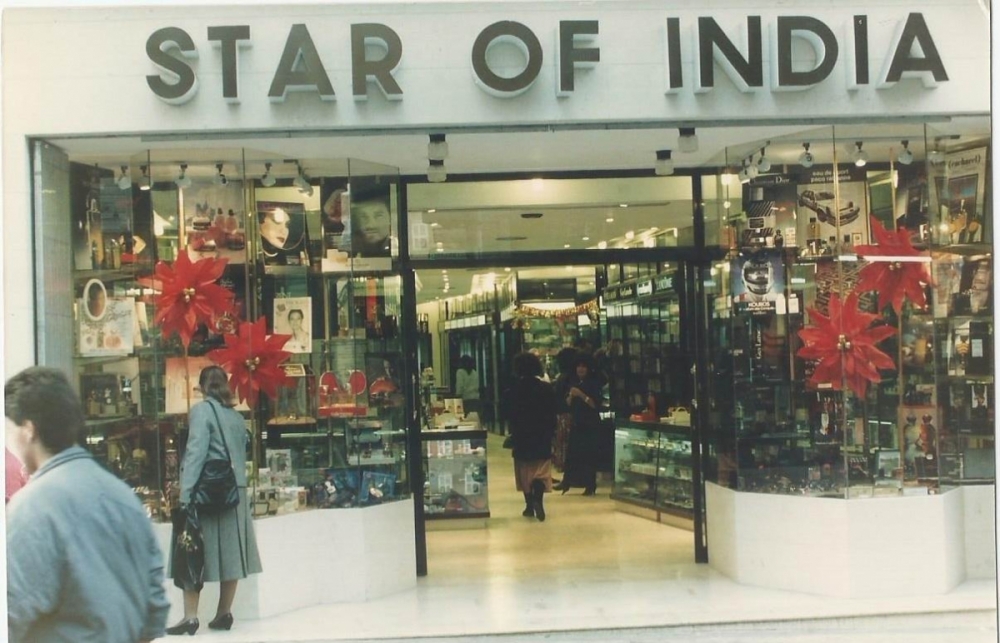

When my grandfather was forty years old, he came back to settle in Hyderabad and his eldest son, Mangharam, took over the business, which by then consisted of several small shops in various parts of Europe, Africa and South America. My uncle Mangharam found the business too scattered and diverse and started closing some. He kept a few and the main outlet was his store Star of India, in Gibraltar. In time, he sent for my father to join him there and they opened another shop for my father to run, Hotu, which was my father’s name.

My father and his new-fangled ways

In 1936, at the end of his first three-year stint, my father went back to Hyderabad and his marriage with my mother was arranged. Having lived away from home and experienced life in a distant foreign country as a bachelor, he was of the opinion that a married couple must have their home together and he announced that he would be taking his bride back with him to Gibraltar. Being of a younger generation, he had these new revolutionary ideas, and luckily got his elder brother’s support to do so.

My mother, Rukmani, a rather timid person who had never been out of Hyderabad before, was soon to become the first woman in our community to join her husband in Gibraltar. It was 1936, a time when most of our women had never been allowed out of the house alone, not even to cross the road. She must have been excited and a bit nervous about going.

To live and work in a foreign country, you had to have a work permit and each store was issued a limited number. Women were not expected to work, so it could not be imagined that a woman would be issued a work permit. I have heard that my father and Mangharam crossed the border from Spain and sneaked my mother into Gibraltar dressed as a man.

My mother was a great reader and she had an educated, analytical mind. She would have made a good lawyer, like her father and brothers. Though from an educated family, being the eldest daughter she had to stay home to help in taking care of the household every time her mother had a child, and ended up never completing her schooling.

In her first year in Gibraltar, she used to be alone at home almost all day. I remember her saying that all she did was cook and cook. The two stores had about eighteen employees between them and they all wanted Sindhi food so she would be cooking kadhi, rice, saibhaji and all those things for eighteen men every day. For other domestic tasks, she had help. Buses crossed the nearby Spanish border every day, bringing labor. She had a maid to dust, clean and do the laundry in huge tubs of galvanized iron, hanging sheets and clothes out to dry on the terrace. But my mother must have gone to the market herself, climbing down three flights of stairs and then back up again with all the provisions, and sitting down to wash, chop and cook.

Gibraltar in the 1930 and 40s

In those days in Gibraltar, there was no regulation about opening and closing times for a shop. Most of the business was done with ships that stopped there. Gibraltar was a fortress and belonged to the British and as it was the entrance to the Mediterranean and strategically a very important point, it needed to be guarded. When British navy ships stopped there, the sailors came aboard to shop. This usually happened at odd hours, quite often in the middle of the night. The moment a ship was sighted or a ship’s horn heard, the men all excited would quickly get dressed and run down the stairs to their stores. And they stayed there as long as the ship was in the port. My father told us that he often slept in the store, on a cot right behind the door. The moment he heard people approaching, he would be wide awake and ready to sell.

My mother spent lonely days, with no other women to talk to. My father was out most of the time, once in a while going with his assistant to the navy ship to deliver merchandise which the captain had bought. When on port leave, the sailors would spend their time shopping and drinking in the local pubs, sometimes roaming around so drunk that they had no idea where they were. Once, searching for a bathroom, they climbed up three flights and knocked at my mother’s door, and she sent them off, while they kept apologizing all the way down about how sorry they were to have disturbed her.

When the laws changed and it became easier for owners to bring their wives, a few more Sindhi women came to live in Gibraltar. While my father and the other Sindhi shopkeepers mingled with the locals and spoke mostly English and Spanish outside the house, the women were from a very conservative society and had never socialized much. My mother did make friends with them and years later, when I got married and moved to Gibraltar and she came to help me during my pregnancies and deliveries, she knew those women and had a special bond with them from way back then.

Rock House, Karachi

In 1940, it was time for my parents to return to Sindh. My mother was expecting me and it seemed wise that she should be back home with the family. But the Second World War had started. My parents were lucky, they got a passage on SS Kemmendine, which had left from England and was bound for Rangoon via Gibraltar. Other Sindhi families also boarded this ship bound for India. When Kemmendine was torpedoed, the survivors were transferred to SS Tiranna, a Norwegian cargo ship which was also torpedoed and sank.

By great good fortune they were rescued and taken ashore. My mother was all bloated from being in the sea for five hours and, pregnant with me, was treated better than an ordinary prisoner in the prisoner-of-war camp. My father was suspected of being a Jew and came very close to being killed.

When my parents returned to Sindh with me some years later, it was not to the ancestral family home in Hyderabad. My uncle Mangharam had lived in Europe for a long time and his tastes had changed. When he came back to Sindh on a visit in 1939, he bought a large plot of land a little away from the Karachi city center and built a large house for the whole family. With his allegiance to the rock of Gibraltar, he called it Rock House. In those days there was nothing across the street in front of our house. In time, it would become a very congested area.

Rock House was a two-story building. The whole front main entrance was built of a rich burgundy-colored marble and there was a fancy wooden staircase going up. Mangharam built a swimming pool in the front yard. At the back was a big angan (courtyard), all beautifully tiled. The women of the family would sit there making papads in the afternoon. They would roll out the dough with their rolling pins and fling them up from where they were sitting onto large sheets spread on the cots or khatta as we called them. I remember them calling out to me as I ran around, telling me to go and flip the papads over so that they dried on the other side too. By evening we would collect them, ready to be eaten roasted, or stored for later. The angan was a place for the women and children. On Sundays we children—so many of us!—got massaged there. And the family gathered there to eat meals together. The system in a big family was that at meal times the men were fed first and then the women would eat what was left over. The menu was catered for the men, so occasionally the women would make a dish they liked but which was not to the taste of the men, just for themselves.

Rock House had four large apartments for each of the brothers’ families. Mangharam and Partaprai had the lower level and my father and Daulatram the upper. Each apartment had its own kitchen but for many years, only one kitchen was used and we had just one cook for the whole family. It was only as we children grew older and had different timings at school that our mothers opened up their separate kitchens to cook for us. Till then, our meals were all directed by their mother-in-law, with the eldest daughter-in-law in charge. Us cousins were very close—just like brothers and sisters. Actually, that’s what we called each other. We weren’t allowed to say we were ‘cousins’. We were a self-contained family, and had each other to keep us company. I think the idea was to stay away from the Muslim culture and not to lose our Hindu beliefs and tradition. We all gathered for prayers for Diwali in our big hall and sat on a sheet on the floor for our pooja, at the end of which each one got kharchi (a cash gift, spending money) from Dada Mangharam. (Continues)

____________________

Courtesy: Sahapedia