Just two years after I set out on this journey into Sindh with my mother, she suddenly and most unexpectedly, died. It was 28 March 2014.

Saaz Aggarwal

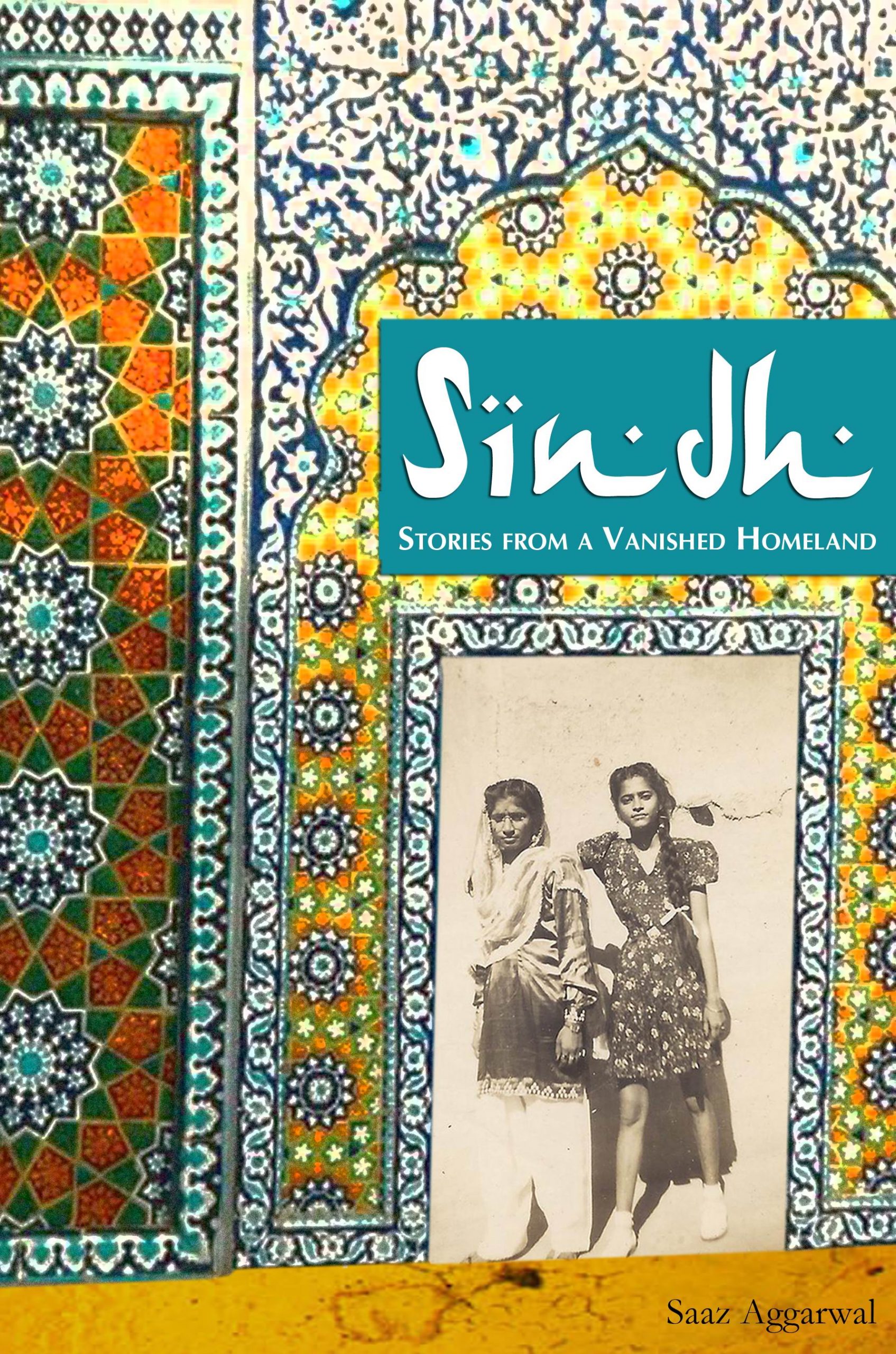

Most books are the result achieved at the end of a long journey. My book Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an exception because it was where my journey into Sindh started.

Published in November 2012, it is a collection of personal stories and the memories of ordinary people, interwoven with facts and opinions from secondary sources. And it began as a memoir of stories of my mother’s childhood in Sindh when I asked her to tell me what life had been like for her and her family before and during Partition, and how they had coped after that.

The most dramatic insight I had into what the migration had done to my mother, who left Sindh at age 13, led me to use the word ‘vanished’ in its title.

“Our families come from five villages in Larkano district,” she told me, and, thinking hard, slowly named them as I typed into my laptop. “My father’s village was Khairodero. Then there was Naudero, where the Bhutto family comes from; and Panjodero and Ratodero. The fifth name eluded her. “I’ll get it!” she promised, “I’ll think and tell you.” And then she shook her head and said, regretfully, “There’s no one left who can tell me that name.”

I keyed the four names into my Google task bar, and began reading out the other names it threw up. When I said, “Banguldero”, her amazed response, “How could you possibly know that!” gave me the poignant realization that, to her mind, those villages had dropped off the map and simply stopped existing when she and her family left Sindh, never to return.

My mother and those of her siblings who were born in Sindh were fiercely proud to be Sindhi. However, they never communicated to us what it meant to be Sindhi, never included us in that umbrella of Sindhi-ness. So though I grew up not knowing anything about Sindh or what it meant to be a Sindhi, I did grow up with an understanding that there was something essential to my mother which I was not a part of. She could read, write, and speak Sindhi – but never shared the language with us. She never spoke about her childhood – her school, friends, favorite games or snacks, or even about the journey they made to Bombay when they left Sindh forever. They never spoke about why they left.

Perhaps they would have, if anyone had ever asked, but we didn’t.

Eventually, so many years later, when I did finally ask, my mother spoke without reservation. And I was astonished at the extent of her memories, of all that she had carried inside her without expressing it. She told me, “When I close my eyes, I can still see those places.”

Just two years after I set out on this journey into Sindh with my mother, she suddenly and most unexpectedly, died. It was 28 March 2014, 8 years to this day. I was grateful to be by her side as she passed on, grateful to receive her last blessing. But the regret is everlasting: all those many questions I have for her which will forever remain unanswered. Fragments of incidents from her childhood in Sindh, which she was still telling me, can never be completed. Sorting out her things over in the days that followed, I came across something she had written many years ago and felt both sad and happy to read it, my mother Situ’s contribution from the beyond:

When I was newly married, my husband’s English boss asked me which part of India I was from. I told him, and he replied, “Oh, so you come from the desert!”

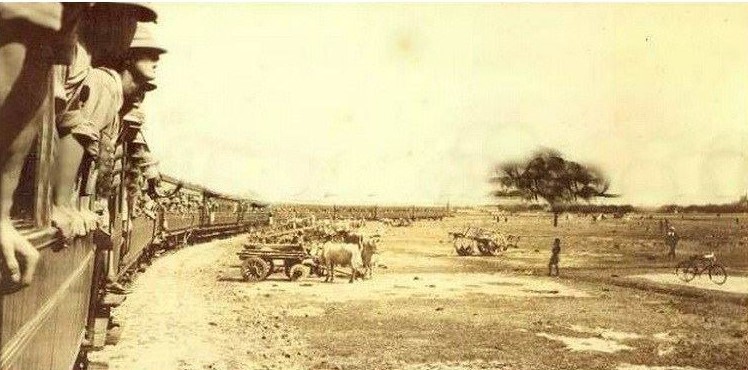

When I responded indignantly with information about our Indus and its many dams, which I had learnt at school, he laughed, and told me about the time he passed through Sindh during the Second World War. The train stopped at an isolated place. Looking out, he saw a jawan from his regiment standing on the platform and gazing contentedly around him. He asked the jawan what on earth he was doing, out here in the desert.

The man snapped back, “This is no desert, sir! This is my home.”

_________________

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.