Scottish photographer stayed for over 40 years in India documenting the colonial officers. He also authored his memoirs ‘My Forty Years in India’.

Sindh Courier

Fred Bremner was born in 1863 in Aberchirder (also known as Foggylone) in Scotland and was one of several sons of a photographer in Banff. He left school at the age of thirteen to join his father’s studio and worked there for six years. In 1882, Bremner accepted an offer of work from his brother-in-law G. W. Lawrie, who ran a successful photography business in Lucknow, India and was assigned work throughout northern India (modern India and Pakistan). He was 20 years at that time.

After the first two years of scouting neighboring towns, for his next assignment he was sent 1500 miles away to work in Karachi where he arrived via Lahore in the summer of 1885. The British had captured Karachi in 1839 when it had a population of only ten thousand. However, at the time of his arrival, Karachi had become an important sea port for overseas commerce for Sindh, Balochistan and Punjab provinces and its population had risen to a hundred and fifty thousand.

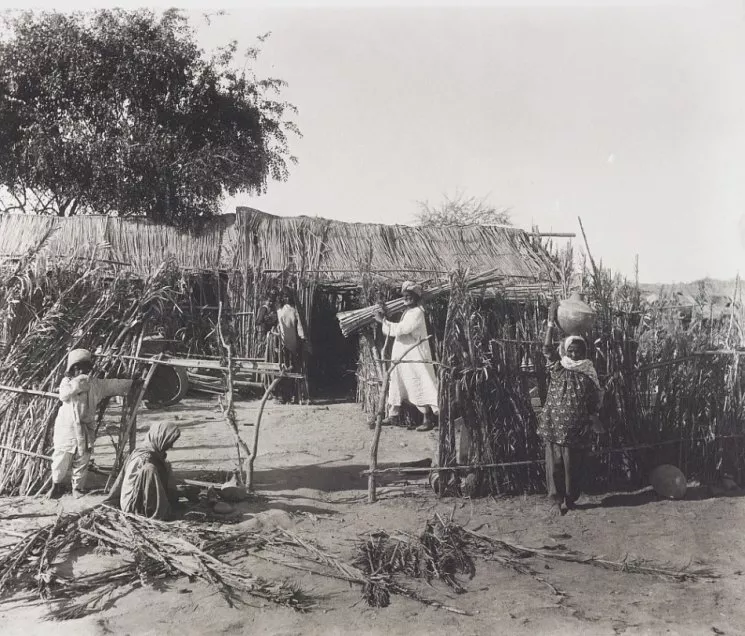

In 1889, Bremner established his own photographic studio in Karachi, and successively studios in Quetta, Lahore and Rawalpindi. He travelled great distances to rarely photographed areas, and his work therefore captured a scarce record of rural life, landscapes and people in late 19th and early 20th century India from 1882 to 1922.

Even though prior to his arrival he had little acquaintance there, but his contacts with a Scottish regiment in Karachi saved the day for him. He was soon able to meet a Barrack Master Richardson who belonged to the Scottish Lodge of Freemasons, the organization Bremner had done business with earlier. Richardson took him as a paying guest and also introduced him to a chemist friend who allowed the young photographer to set up his studio tent in his yard.

Bremner worked in this set-up for the next five months. During this time he also hired two local assistants who helped him with retouching, printing, finishing and hand coloring. At the end of his assignment he left Karachi in 1886 and did not return to the city for the next two years. In April 1888 his contract with Lawrie had ended, his sister had died and he wanted to go home. So he returned to Karachi to take a ship for the British Isles.

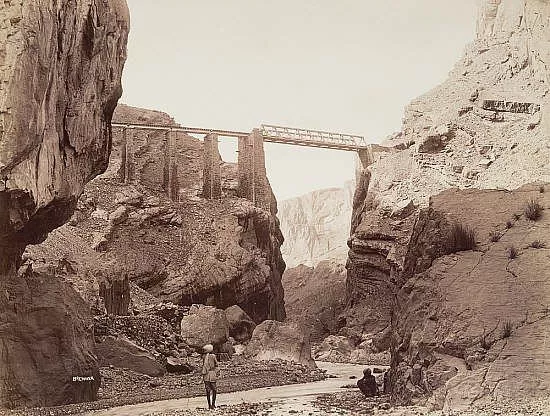

Upon his return from England in 1889, Bremner decided to open his studio in Karachi, the fledgling capital of Sindh. Through his savings he had bought some equipment from Glasgow and paid for the fair for himself and his one assistant whom he also had brought to Karachi with him. However, after paying for all that, he had very little money left to sustain. Luckily the opening of the Sukkur Bridge across the Indus by Lord Reay, Governor of the Bombay Province on March 25, 1889, afforded him photographic commissions to sustain his business.

More studios followed at various times in Quetta, Balochistan, and in Lahore and Rawalpindi in Punjab. The picture postcards carry the names of cities where Bremner had his studios at the time of issuing them. In 1910, Bremner opened a summer studio in Simla, the summer capital of the Raj. He married in the following year and was assisted in his work by his wife who newspaper ads referred to as “especially helpful with purdah-observing ladies”.

Some of the prominent and distinguished sitters Bremner ‘shot’ during his years in India were the viceroys Lord Minto, Lord Hardinge, Lord Chelmsford, and Lord Reading; Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Lord Kitchener, and Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Governor of Punjab. He also photographed the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) during his tour of India in 1922. Among the Indian nobility, he worked for the Nawab of Dholepore and later for the Maharajah of Jind, the Nawab of Maler Kotla, and the Maharajah of Kapurthala. He often photographed the Khan of Kalat in Balochistan.

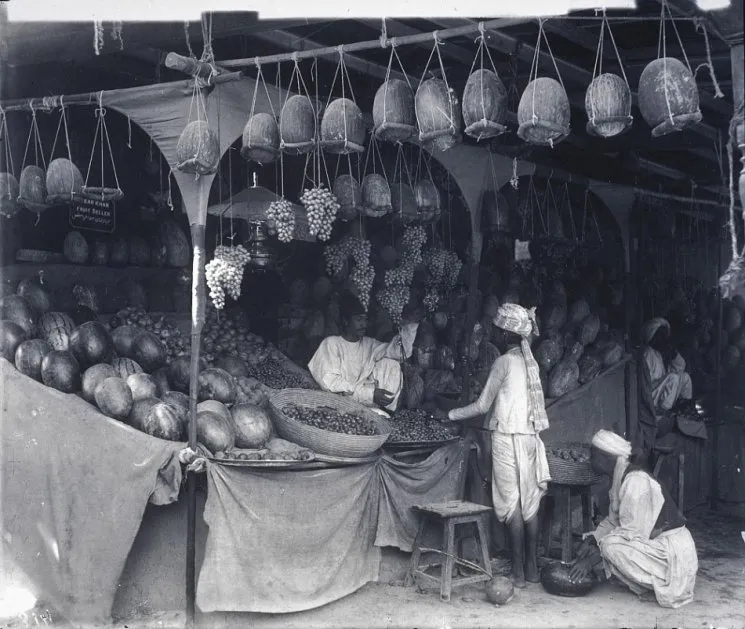

Working with the British Indian army and occasionally for the member of British and Indian elite provided the mainstay of business, in addition to income from the retail shop. Since most newspapers even in the west carried a few pictures before 1910, situation in India was not any better. Colonial photographers like Bremner made the best possible use of growing European interest laden with imperial ambitions in picture postcards of foreign lands which were often colonized territory.

In 1900, he published a photographic album titled Baluchistan Illustrated, which contains the only surviving photographic records of Quetta before it was destroyed by the earthquake in 1931. The photographs and images of architectural monuments of Lahore also were a favorite subject for postcard publishers to reflect the ancient purity of traditional culture of the past. The hotspots of photographic activity for the picture postcard publishing were Mughal monuments such as Masjid Wazir Khan, and Lahore Fort. The Gates of Lahore, especially Delhi Gate and Lahori Gate were actively photographed and produced on postcards. The aesthetic conventions of these images — the medium in which they were executed and the manner in which they were framed — served to isolate the past from the present.

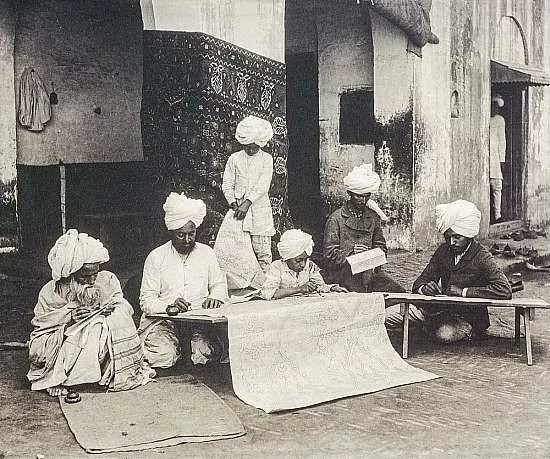

While photographing army officials in Rawalpindi he observed the characteristic of different ranks and decided to conduct a three-month tour to prepare a photographic series. The album on the martial races in the Indian Army was intended to be used as a companion to military recruitment manual and contained 60 Collotype prints with the Sikhs well represented. The group photographs portrayed uniformed soldiers in front and side positions, standing and sitting on houses in museum-like poses that indicated their orders of dress in relations to each other.

Fred Bremner used collotype process which was popular in the early 1900s for his publications. He published numerous books namely, Types of the Indian Army (1900), with text by A.H. Bingley and 60 bromide prints by Bremner; The 1st Battalion Wiltshire Regiment ‘The Springers’ (1900), with 26 collotypes reproductions from Bremner’s photographs; The 2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment (1900), with 38 collotypes; Baluchistan Illustrated, 1900 (1900), with 50 collotypes.

His income for several years came mainly from army photographs, even after he established himself independently. But by 1902, he moved on to other projects, including the Delhi Durbar. The Delhi Durbar, a mass assembly to mark the succession of the emperor or empress of India, took place thrice under British rule: 1877, 1903 and 1911. He travelled a fair deal and was commissioned to create portraits of viceroys, maharajahs, nawabs and even the Prince of Wales.

Bremner left India in 1923, although business continued until about 1932. He produced a number of books photographically illustrated in collotype at the turn of the century. He also wrote a memoir of his life ‘My forty years in India’, privately printed by the Banffshire Journal Ltd., Banff and Turnilt, 1940.

As an independent photographer, who worked largely in the far flung areas of the Raj, such as Balochistan and Sindh, Bremner is more likely to be forgotten. His memoirs My Forty Years in India, (1883-1923) complete with twenty one autotype reproductions of his work, which Bremner privately issued twenty years after he retired to England, is perhaps the only record of a pioneer postcard publisher in Northwestern India.

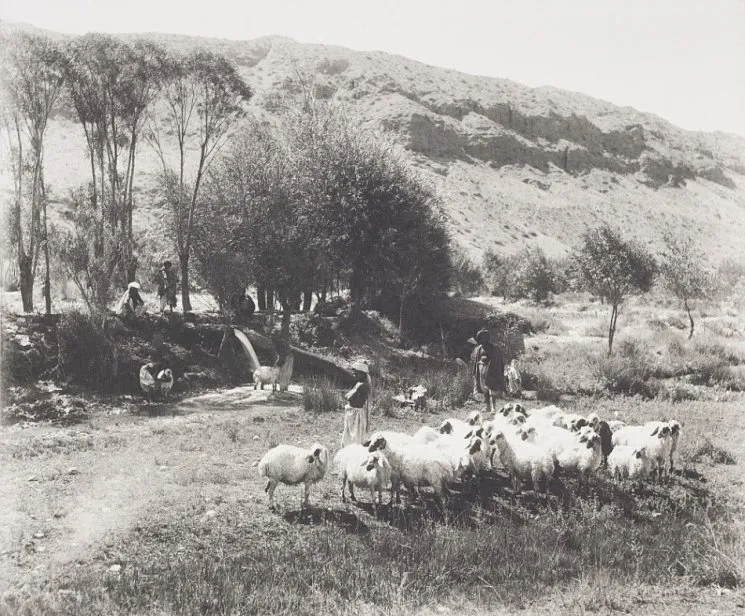

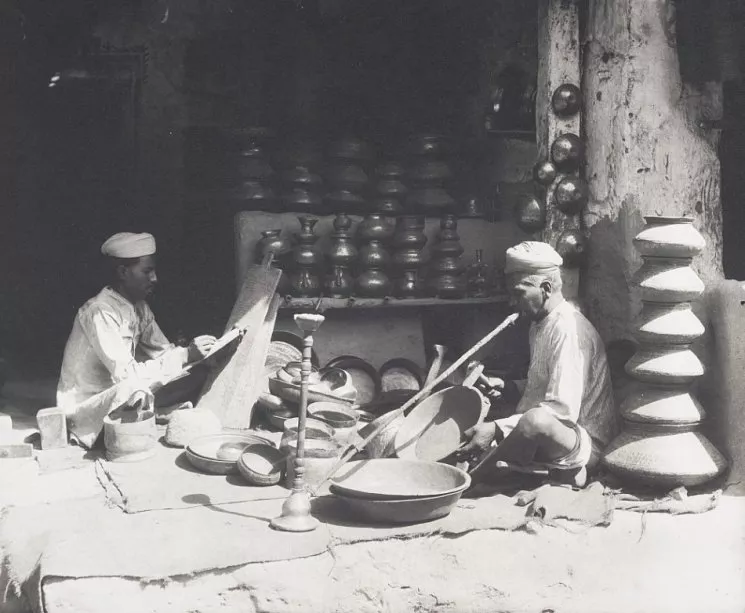

An exhibition at Scotland’s National Portrait Gallery, featuring a rare collection of photographs by Scottish photographer Fred Bremner, explored life in India during the British Raj. The exhibition, called Lucknow to Lahore: Fred Bremner’s Vision of India, was held in April 2013, and showcased photographs taken in what was then called the Indian subcontinent, between 1882 and 1922. Bremner’s collection features photographs of artisans at work, India’s everyday life and local culture; the photos clearly depict India as a wealthy country.

In many photographs, Bremner while comparing Kashmir and Switzerland, had stated, “Switzerland is without the charm of oriental life, the quaint manners and customs of the people…which all add to the attractions of a trip to the Valley of Kashmir,” Bremner wrote of his photographs of Kashmir in 1896.

In many photographs, Bremner while comparing Kashmir and Switzerland, had stated, “Switzerland is without the charm of oriental life, the quaint manners and customs of the people…which all add to the attractions of a trip to the Valley of Kashmir,” Bremner wrote of his photographs of Kashmir in 1896.

In 1923, Bremner sold his established studio in Shimla and returned to the UK. Seventeen years later, he published a memoir, My Forty Years in India.

Bremner, who died in 1941, was a talented practitioner of photography, but he also had an unusually well-developed sense of the meaning and potential of the form, at a time when people were not very concerned with its theoretical aspects.

“Artists – painters, I mean – tell us that photography is not a fine art,” he wrote in Forty Years. “Cut out the word ‘fine’ and art remains. Certainly mechanical means have to be used up to a point, and many amateurs believe that when equipped with a nice camera and lens nothing else is necessary. The ‘button’ does the rest. Believe me it is the man or the woman behind the instrument that matters.”

______________________

Source: Scroll, Luminous Lint, Maddifycation, The News, Wikiwand, ibtimes, Photography and Vision