The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse.

Julien Levesque

[The study of Sindhi nationalism has remained over-determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state. The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. As a result, it has mainly received attention when sudden outbursts of violence seemed to threaten the stability of the state. However, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails. Rather than address questions of failure or success, this article shows that the construction of a nationalist “idea of Sindh” has been a continuous process throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It also illustrates how an aspirational middle-class played a central role in this process. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse. This process translated into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributed to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.]

Colonial Policies and the “Separation” Generation (1920s–1940s)

The nationalist idea of Sindh did not emerge with G. M. Sayed but under colonial rule when a section of the Sindhi political elite fought to establish a separate Sindhi province. A century (1843–1947) of colonial policies impacted both the culture and social structures of Sindh in at least two significant respects. First, the British administration fixed Sindh’s current borders and exerted (or aimed to) its authority uniformly over the territory and its inhabitants. Second, the British rulers standardized the Sindhi language based on the central vicholi dialect, for which they invented a new modified Perso-Arabic Naskh script. The writing system allowed a single community of letters to emerge where multiple community-based scripts previously divided speakers of a common language. Moreover, its promotion by the colonial state led to the emergence of a vernacular print culture with an active press, new writing styles, and the canonization of literary figures, such as the Sufi saint Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai. These developments allowed Sindhis to subsequently construct a nationalist discourse that revolved around a common literature and Sufism as an “ideological pillar” or “identity marker.”

Moreover, colonial history-writing placed Sindh at the center of the narrative of the spread of Islam in India. Colonial historiography thus “produced … synthetic narratives [that] created the discursive grounds for Sindh as a political space.” In addition, the “semi-representative electoral system” set up in Sindh, as in other parts of British India, de facto made it a political space by giving rise to the need “for the political classes … to flatten out differences in the interests of producing a larger, more homogenous electoral community.” Colonial policies thus “participate[d] in the creation and reification of social groups with their varied interests” by bringing about three elements – fixed borders, standardized language, reified culture – that created the necessary conditions for an “imagined community” to emerge in Sindh.

Those who argued for the separation of Sindh and later for the Pakistan project excluded the Hindu and urban part of Sindh’s culture from the imaginary of Sindhi nationalism. In doing so, they overlooked the significant contribution of Hindus to defining sindhiyyat or Sindhiness.

Sindhis thus adopted new ways of conceptualizing their own culture. Political representatives in the 1920s and 1930s projected Sindh as a single geographical, linguistic, cultural, and historical entity. According to them, Sindh deserved for this very reason to exist as a political entity. They argued for its separation from the Bombay Presidency and for it to be a province of its own. A few years before Gandhi took the leadership of the Indian National Congress and extended its reach beyond elite circles, the demand for a separate Sindh province was put forward in 1913 at the annual session of the INC in Karachi. Harchandrai Vishindas (a Hindu merchant) and Ghulam Muhammad Bhurgri (a Muslim landlord) stated that “the Province possesses several geographical and ethnological characteristics which give her the hallmark of a self-contained territorial unit.”

In the 1920s, much like India’s politics, the project took on a communal tinge. On the one hand, many Sindhi Hindus withdrew their support to the scheme because a separate Sindh would turn them into a religious minority – they represented about one quarter of the total population. On the other hand, the Muslim League announced in 1925 its support to the “separation movement,” hence making it a pan-Indian and a Muslim issue.

Although the justification for “Sindh’s separation” hinged on economic and political terms, politicians ultimately framed the key moral argument in favor of a separate province in nationalist rhetoric that highlighted the historical and cultural continuity of Sindh. This nationalist framing appeared in what became the most well-known argumentative piece of that time, a 50-page pamphlet entitled A Story of the Sufferings of Sindh: A Case for the Separation of Sind from the Bombay Presidency. Muhammad Ayub Khuhro, a 29-year-old Muslim landlord from the northern town of Larkana and head of the Khuhro caste, published it in 1930. According to Ayub Khuhro:

The proof of the fact that Sind was a very important and a highly civilized country even 5000 years ago, is furnished by the recent discoveries made by the Indian Archaeological Department at Mohan-jo-Daro (Sind) … I have briefly traced the history of Sind from 5000 years back down up to the British conquest and the Governorship of Sir Charles Napier. During the whole period, the historical record shows that Sind has never been usurped [sic] by any other province and it is really inconceivable how British Government has deemed it right to allow the Bombay Presidency to swallow Sind.

Ayub Khuhro’s trajectory represents the generational experience of young elite Sindhi Muslims in the first half of the twentieth century. Khuhro, like many other sons of Muslim landowners of his era, was educated at the Sindh Madrassatul Islam in Karachi. Although Sindhi Hindus had long had access to a Western-type secondary and higher education, this was not the case for Sindhi Muslims before the establishment of the Sindh Madrassatul Islam in Karachi in 1885 and similar institutions subsequently founded in other towns and cities. Khuhro was elected to the Bombay Council in 1923, at the age of 22, and was involved in organizations that sought to represent the Sindhi Muslim voice, such as the Sindh Provincial Conference, the Sindh Zamindar Association, or the Sindh branch of the National Mahommedan Association. For Khuhro, this implied moving to the centers of power, Bombay and Karachi, and leaving his hometown Larkana – without, however, severing ties, since he remained a large landowner and the head of the Khuhro clan. Although Khuhro belonged to an exceptionally powerful family, his social profile nevertheless exemplifies what characterized the “separation movement” supporters – the “separation generation” – who formed the new Sindhi Muslim elite that entered the public arena in the 1920s. These men tended to be sons of Muslim landowners who had studied at the Sindh Madrassatul Islam. They followed a rural to urban migration to seek employment in non-manual urban sectors – administrative services, private professions, and in political institutions such as town councils.

Both the separation movement and the Pakistan movement fed on the same emancipatory thrust that sought to place power in the hands of the majority population of Sindh, that is, Sindhi Muslims. Both aimed to give a common cause and representatives to Sindhi Muslims.

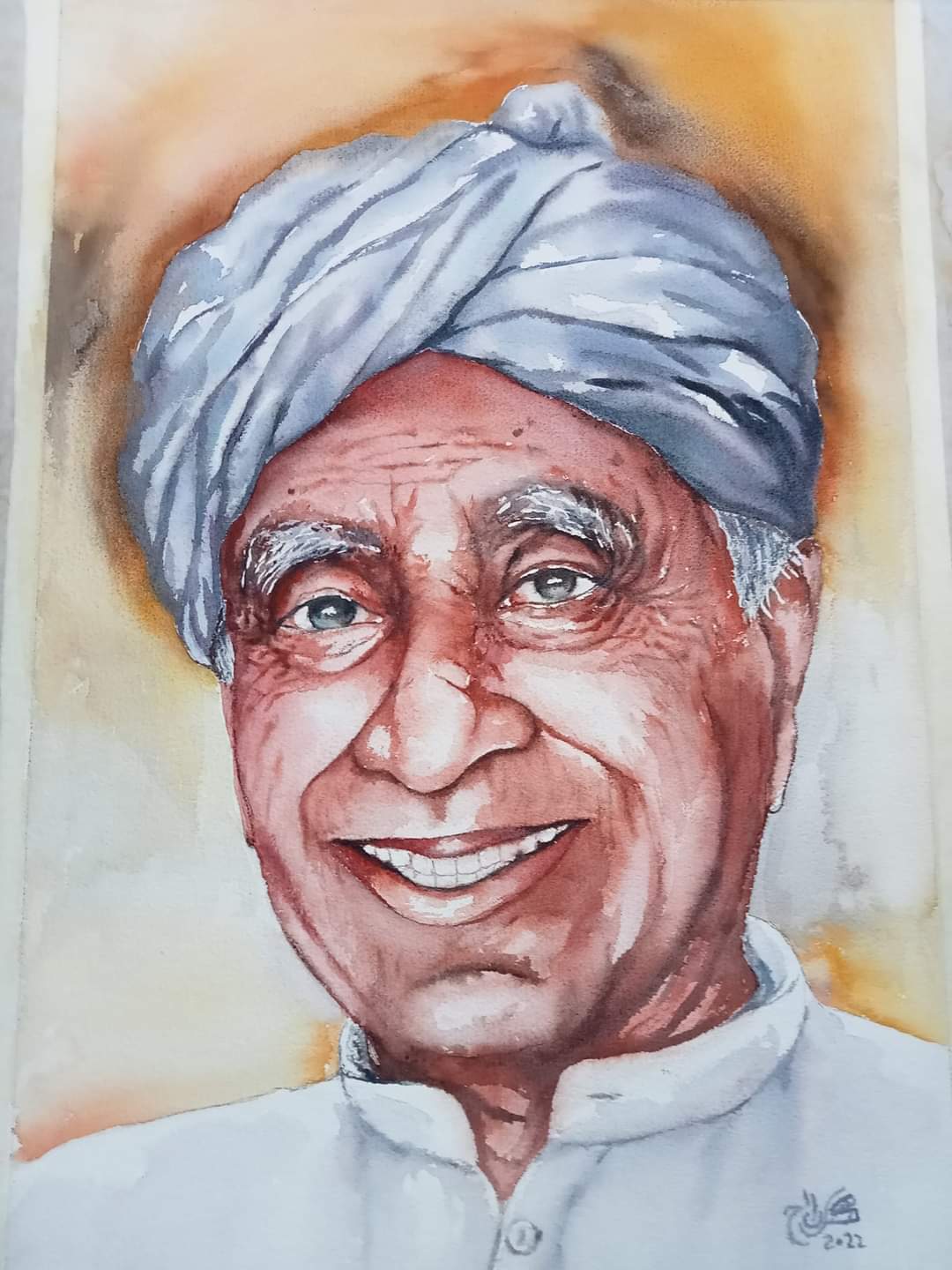

After Sindh became a province in 1936, the new Sindhi Muslim elite increasingly endorsed the Muslim League’s Pakistan project. The latter thus appears as a continuity of the former. Firstly, both movements framed their demands as a way for the new Muslim elite to access government employment and urban jobs. This framing implied getting rid of the domination of Hindu administrators (amil by caste) and businessmen (bhaiband), vilified as the “bania money-lenders” from whose “clutches” poor Muslims had to be relieved. Sindhi Hindu merchants were targeted because of the amount of land they had acquired through mortgages from Muslim landholders. Other groups were also perceived as harming the rights of the “indigenous population.” “Numerical anxieties” were directed at Punjabis, who had recently settled in Sindh after the completion of the Sukkur barrage in 1932. What “being Sindhi” meant was now debated at the provincial assembly, with voices asking for ethnic preference in government employment – notably that of G.M. Sayed. Secondly, some Sindhi Muslims projected the imagery used to support the demand for a separate Sindh into the Pakistan project, making it a Sindh-centric representation. The speech by G.M. Sayed quoted earlier suggests that there was in the 1940s a “Sindhi understanding” of the Pakistan project. We should also note that those who argued for the separation of Sindh and later for the Pakistan project excluded the Hindu and urban part of Sindh’s culture from the imaginary of Sindhi nationalism. In doing so, they overlooked the significant contribution of Hindus to defining sindhiyyat or Sindhiness.

Both the separation movement and the Pakistan movement fed on the same emancipatory thrust that sought to place power in the hands of the majority population of Sindh, that is, Sindhi Muslims. Both aimed to give a common cause and representatives to Sindhi Muslims. Political representatives who came from the new Sindhi Muslim elite and spoke in the name of Sindh did not significantly change the way they conceived their role as they threw their weight behind the Pakistan project. As its entrance into the public arena eroded the old power nexus, the new Sindhi Muslim elite relied on a particular repertoire of contention – that of representative politics and press advocacy. Having understood that the claim to political autonomy had to rest on cultural unicity, these men laid the foundations of the Sindhi nationalist discourse by arguing that the cultural and historical specificity of Sindh justified it becoming a separate political entity. The same idea later found its way into the Pakistan project. This discourse invoked a set of cultural references that gained progressive acceptance as symbols of Sindh’s cultural essence, such as Sufi saints and spirituality, the Indus civilization and Mohenjo-Daro, language, food, and dress. (Continues)

_________________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence.

Courtesy: Brill

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Click here for Part-I, Part-II