The languages we grow up with, the words and expressions used around us, influence our thoughts and behavior. And the Sindhi of 1947 was a language packed thick with phrases and concepts from the region’s philosopher poets of the previous few hundred years.

Saaz Aggarwal

Sometime in mid-2012, I asked Niranjan Gidwani to tell me his family’s Partition story.

Till then, I’d only known Niranjan as my husband’s friend, a good guy, and never thought about him as a Sindhi or anything like that. But I’d just started working on a book about Sindhis and it was amazing how all kinds of unexpected sources were popping up. Niranjan told me some interesting things, including how his grandfather, a fairly well-off and influential person in Sindh, went missing in the turmoil before Partition. His younger son was general manager of the Great Indian Peninsular Railways, and arranged for a private bogey for the family to move their things as they left Sindh. However, the labor bringing their furniture and personal belongings never reached the station. Later, his grandfather’s body was found cut up in pieces in a sack, under a railway bridge. “Till today,” Niranjan said, “no one really talks about this ever turned hardship into success and thrived by assimilating into the host society.”

This was the first example I’d heard of barbaric atrocity coming out of Sindh, and over ten years and many interviews, it is still one of very few. Even with no one really talking about such things, the extent of violence in Sindh is much less compared to what happened in Punjab where there was no family without its own horror story.

This big difference is the main reason why people who left Sindh always considered themselves the lucky ones and therefore did not feel they had a story to tell. But they did.

What somehow slipped out of this broad context was that while Punjab and Bengal were split in two, Sindh was given intact to Pakistan. The Sindhis who moved to India had no homeland to call their own. They left their only homeland behind. And when the minority community Sindhis were forced out by ominous threats and pointed discrimination, they had to start afresh in unfamiliar places among unfamiliar people, where the food, clothes, habits were alien to what they were accustomed to – and the languages was written in the opposite direction.

Niranjan told me some interesting things, including how his grandfather, a fairly well-off and influential person in Sindh, went missing in the turmoil before Partition.

Many Sindhis settled in centers of employment and trade – Bombay, nearby Pune, Delhi and places easily accessed from the border including Ahmedabad and Ajmer. Aruna Jethwani, 13 when Partition took place, remembers that neighbors in Ahmedabad and Nadiad were good and helpful. However, before renting an apartment, her father had to sign a declaration that no meat would be cooked or eaten on the premises. Reaching out to touch laundry flapping on a line one day, she knew what it meant to be an inauspicious omen when a woman screamed, “Nirvasi chho – you are homeless!”

The taint of disdain was felt all over.

In Gibraltar in October 2013, Suresh Nagrani stood up to speak after my talk. “When I was young,” he started, “I thought all Indians were Sindhi.” Everybody laughed. The thing is, though, the Indians native to Gibraltar are indeed all Sindhi. They form part of the trade diaspora that originated in the 1850s, soon established itself in ports around the world. Suresh went on to describe the jolt he got at university in England where he met Indians from different parts of India – and one of them said to him, “Oh, so you are a Sindhi. Let me ask you a riddle. If you meet a Sindhi and a snake, which one should you kill?”

Perhaps the prejudice Sindhis faced began after Partition when many of the homeless ones took to trading at low margins, creating resentment among established traders. And perhaps this was reinforced by the stereotypical negative characters in Hindi films who had Sindhi names and said nasty, exploitative things in Sindhi accents, set up as comedic personas, even until the 1990s.

Beneath that public perception lies a gentler reality. Reyhaan Datta who grew up in Calcutta remembers a Sindhi sari seller from whom her mother bought beautiful saris – a softspoken person whom her mother would offer tea. One day he told them that it would be his last visit. He had been a skin specialist and had left Sindh with his wife and mother with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Selling saris from door to door was the only occupation he could find—living simply and saving, he had now saved enough to buy a practice with a leading Calcutta skin specialist.

It is stories of this type that pervade every family that left Sindh, stories of enterprise, frugality and eventual assimilation and success.

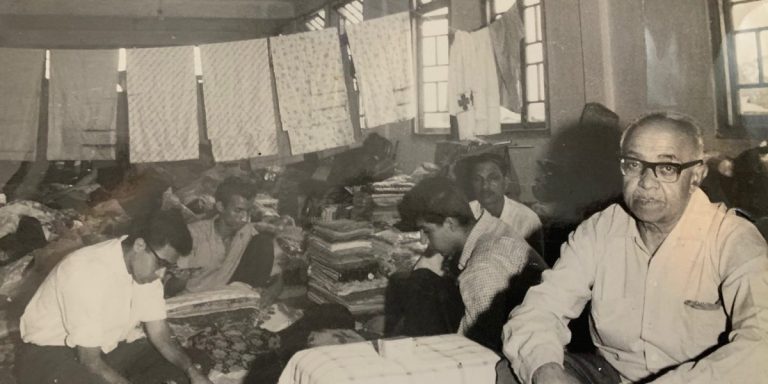

From the ‘refugee camps’ in which the new Government of India accommodated the masses displaced by Partition, the Sindhis grew as successful as a community and set up many schools, colleges and other institutions that continue to serve the community. Being homeless, the Sindhis built homes for themselves; in time, they would change the skyline of these cities. Scattered over the globe with a few pockets of some density, the Sindhis rebuilt their lives of comfort and dignity by integrating into the communities where they settled. For a community that lost all their material possessions and three homeland, they were able to regain a remarkable degree of prosperity in time. And, just like that most families also spontaneously stopped talking to their children in their mother tongue. Assimilation and cosmopolitanism also meant loss of language and culture.

The languages we grow up with, the words and expressions used around us, influence our thoughts and behavior. And the Sindhi of 1947 was a language packed thick with phrases and concepts from the region’s philosopher poets of the previous few hundred years.

Herkishendas Melwani left Sindh in 1939 to work in the global retail chain of Lalchand Dhalamal, was never able to return when exiled by Partition, and settled in Shillong. Anglicized due to his social station and education, Herkishendas never loses his Sindhiness and quoted and lived by his Sindhi pahakas (sayings).

His son, Murli Melwani, who taught in Sankerdeb College in Shillong till he had to leave because of political forces, became a businessman in Taiwan and later the USA, was acknowledged recently by Sahitya Akademi as a Sindhi writer wrote about his father’s classic Sindhi responses to all hardships here.

The Sindhi pahakas – shaped by and reinforcing the multi-faith harmony of the land – defined the mindset of a people who chose to accept their fate, protect their womenfolk, adapt to lives in other places. They continue to pervade the Sindhi identity—somewhat. Because there is no place the community has access to where their language is spoken on the streets. Sindhi is a language that you only hear in the homes of relatives, it’s the language of intimacy but of the lost country. It is the language you hear your grandparents speak to each other and to those of their children who knew Sindh – never to you. Because you had never known Sindh, and it would be impossible to explain anything as important, as essential, and as complicated as that.

_____________________

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwal/ The Wire