In October of 1947, a Sikh milkman was stabbed in a residential neighborhood just a few streets over from Bunder Road.

By Sheila Sundar

In 1943, the war pounded relentlessly and the boats of soldiers continued to dock in Karachi before moving to battles further east. With no end in sight, the British government allowed Karachi’s families to return home. Narayan had failed the end-of-year exam in Kallidaikurchi, which had been administered in Tamil, and was relieved to return to his English-medium classroom. He left his grandparents’ agraharam, with its limitless supply of milk and yogurt, to a city of ration cards. The plastic tokens were still in circulation, but the fruit vendors outside of St. Joseph’s School had disappeared. The soldiers were still present, but they had retreated again to their military campuses and barracks, appearing only to shop the outdoor markets and have their shoes shined, but never again joining the boys at the cricket field.

Mr. Ponniah had been right about the British. On August of 1947, Narayan and his family sat beside their radio and listened to Prime Minister Nehru deliver his speech on India’s tryst with destiny. Even Kamala sat beside them. She was newly married, and discussion of independence touched only the margins of her life. She had one year of school remaining, and although she was at the top of her class, she would soon leave school—and Karachi—to move to her husband’s village in the south. She sat on the floor beside their mother, whose life foretold her destiny more than any change in the country’s governance.

Raghavan was overcome by joy, and let the children join the crowds assembling on Bunder Road. But Narayan could sense his father’s ambivalence in the coming months, as discussion of independence hung over their lives. The British had built the contours of his world. Every monthly tuition payment, housekeeper’s salary, and tile in his home was a product of his ability to function within British rule. On that evening, however, neither Narayan nor Raghavan felt any such conflict. The streets erupted and the family ran outside.

When in Kallidaikurchi, Narayan had desperately missed the constant shaking and movement of Karachi. The air in the village was still, and he could not envision any future beyond the daily rituals of his family’s life. The news of independence made it clear that, unlike his family’s life in the village, Karachi’s future was thrillingly uncertain. He imagined his grandmother and aunt, their lives only slightly stirred by the end of colonial rule.

Kamala was silent on the matter. Independence changed only one detail of her life. The week after Nehru announced the country’s freedom, their mother visited the school and insisted that her daughter—newly married and freed from British rule—be granted permission to trade her skirt for a sari. Watching her attend St. Joseph’s in her final months, Narayan began to wonder about the many Indias contained within his country’s borders, even within the same family. Kamala completed the school year in a sari, then prepared to join her husband in his family’s village.

Narayan was comforted by his father’s steady presence in the weeks following independence. Raghavan, in turn, was comforted by his proximity to Mr. Ponniah and BBC Radio. He was also surrounded by close Muslim associates, and the cushion of community softened the increasingly alarming reports from beyond Karachi.

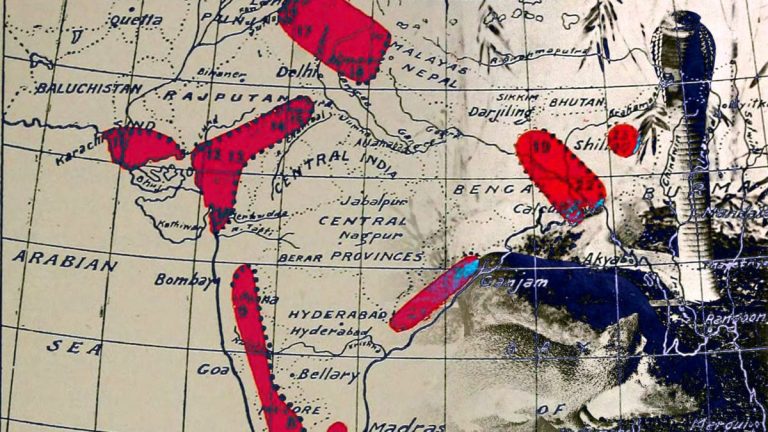

Narayan knew from his father’s reports that India would be partitioned into a Hindu and a Muslim nation, that a confluence of voices in support of and opposition to this decision had resulted in one final act of British control. A man named Cyril Radcliffe, who had never set foot in India, would chair the commission to divide India from the new nation of Pakistan.

Were it not for BBC Radio, Narayan would never have known that Karachi was no longer part of India that his home and family sat squarely in the center of the new country’s first capital city. For several months, it was easy to dissolve all memory of Partition, because in its place came a steady return to the rhythm of school and governance, of systems that the British built but did not have to remain to oversee.

In October of 1947, a Sikh milkman was stabbed in a residential neighborhood just a few streets over from Bunder Road. Raghavan was disturbed, but he sought comfort in his Hindu and Muslim colleagues who continued to build their lives in Karachi, maintaining a loyalty to a unified, undivided, and independent India. Narayan shared these sentiments. Independence increased his allegiance to his country, even in its divided state.

In the months following the murder of the Sikh milkman, a group of Muslim refugees from East Punjab were forced out of their homes. They moved across the new border, settling first in Lahore and then in Karachi. They were shaken by the violence in East Punjab, and carried scars and stories of attacks by Sikh mobs. Narayan heard of their presence, and Raghavan and his colleagues knew that the Pakistani government was under new pressure to respond with a single, unified promise of security.

As the silence of the Pakistani government continued, the Muslim community’s rage against the city’s remaining Sikh population grew. A group sought revenge at a Gurdwara, a Sikh religious center in Karachi’s center, where Sikh families from the neighboring Larkana area of Sind had moved to prepare to migrate to India.

Narayan had difficulty naming the villain that was tearing the country apart. Months before, it had been the British, but he was always aware that there were places where colonial power gave way, and a few Indians could assume a place within these gaps in the empire. Now, news from the Gurdwara floated through the community of Bunder Road, although nobody admitted its brutal reality in the children’s presence. Narayan eventually learned that Sikh families had been murdered as they waited, captive and marked, to attempt to migrate to India. And he heard from his father’s Muslim friends that the same attacks were being waged on the Indian side: Hindus murdering Muslims as they attempted their move to Pakistan.

The newly demarcated border had produced new and unfamiliar names—Radcliffe Commission, Hindustan, Muslim League, Pakistan—but nothing to alter the course of daily life prior to this attack. The single killing of a milkman had been easily dismissed as a murder. But the murder of innocent people in their Gurdwara, at the hands of people who had themselves survived the slaughter of their villages, prompted a new sense of impotence that Raghavan had not yet felt, even as he heard of religious clashes in distant cities and villages.

The family hoped to leave Karachi together, but Raghavan continued to feel responsibility to the British government even after independence. He decided to remain at his post but sent his family—his wife and five children, including a newborn son—on a plane to Bombay. They would then travel by train to the south, where he would join them once he completed the years of work needed to collect his pension.

Repeated attacks aboard trains raised the costs of air travel. Still, Raghavan had the means to pay for safe transport, and purchased the six tickets to land his family safely in Hindu-dominated India. As the date of departure grew closer, Karachi’s South India Association met and formed a policy to govern migration. Air tickets would be reserved for women and young children. Men and older boys would board any available boats or trains, risking the sectarian violence that they knew, through BBC Radio and survivors’ accounts, accompanied the journey. Families would separate for travel, increasing the odds that some members of each unit would survive. Those who had purchased airfare would sacrifice their seats to members of other families. Survivors would reunite in India.

Raghavan gave two tickets to a neighboring family. His wife, two daughters, and infant son boarded a Tata Airlines flight bound for Bombay. For Narayan and his younger brother Swaminath—sixteen and thirteen years of age, respectively—Raghavan learned of a cargo ship, the S.S. Englistan. Normally traveling between Australia and Saudi Arabia to carry sheep to Mecca for sacrifice during Eid al-Adha, the ship had been diverted to bring refugees from Karachi to Bombay. In place of private compartments, it had a large open deck, built to sustain animals only for the duration of the one-way journey.

On the day of travel, Raghavan stitched an envelope containing a thousand rupees into Narayan’s pant leg. Raghavan planned to see his sons off at the Karachi Harbour, but several kilometers from the port, they were stopped by British Military Police and Raghavan was directed to turn back. In a final request as a servant of the British government, Raghavan told the officer his official title and asked permission to escort his sons to the port. The officer rejected his plea, and the boys were pulled away, toward the chaos of the cargo ship. Over the years, as Narayan studied his father closely, Raghavan’s power over both his life and the lives of those around them had never been compromised. But Narayan had also observed in people the convergence of powerlessness and authority, the ability to hold in place the rules of society and govern the decisions of others, while being unable to alter the course of their own lives. Raghavan stayed in place, growing smaller in Narayan’s vision as the boys approached the port. It was the first time he had seen his father lose a battle, and the first time he had seen him cry.

Overburdened with passengers, the ship hugged the Indian coast. On the deck, families clawed past strangers, seeking familiar faces and news of survivors from their areas. Narayan later learned that most of the passengers were from Upper Sind Province, and had been forcibly removed from their villages with little warning. Now, severed from the city of his childhood and the surrounding provinces, he came face to face with the fragmented identities that made up his nation. Swaminath, overcome by motion sickness, lay sweating on the floor of the ship’s deck. Narayan left his side only once, to walk to the upper deck and get a glimpse of the sea.

Years later, Narayan would describe the experience of watching the water as the boat moved relentlessly forward. On the dock that afternoon, he recalled his grandmother’s multiple pregnancies, Vellamma’s life, the sprinkling of the kolam outside the door, the Brahmin boys with their hands outstretched, and the afternoon he stood in the theatre with his finger pointed at the British soldier. He hoped he would feel that independence again, that he would be the one to steer his own life. But for now, he watched the boat move along the coast, delivering him to a newly broken country. (Concludes)

___________________

Sheila Sundar is currently at work on her first novel, set in South India in the 1960s. Her writing has appeared in The Rumpus, The New York Times, The Bookends Review, and elsewhere.

Courtesy: Guernica, an online magazine on global arts and politics.

Click here for Part-I, Part-II, Part-III