The British ranks swelled in Karachi as troops traveled to Burma to block the Japanese invasion.

Coins were scarce at the height of war, and each month Raghavan sent his assistant to purchase containers of the plastic bus tokens that conductors accepted in lieu of currency.

By Sheila Sundar

In 1941, when he was ten years old, my uncle Narayan dropped a lit match into the charcoal chute that stemmed from the wall of his Karachi home, and set it aflame. The act mimicked a Hindu ritual he had participated in on visits to his native Tamil Nadu village, in which a lamp would be lit on open ground in front of the temple deity, allowing worshippers to carry home a light from the flame for their evening prayers. In this way the fire was always multiplying while always maintaining its shape. Before lighting the fire in Karachi, Narayan didn’t know that a single match could engulf and consume in the way that it did, climbing up the wall of the house and reducing the clapboards of the family bungalow to ash. The fire seemed to charge toward his face while smoke enveloped him from the back. He remembered, in the moments before two servants ran outside and extinguished the flames with a pot of water, the feeling of two threats converging at his throat, as though choking him into nonexistence.

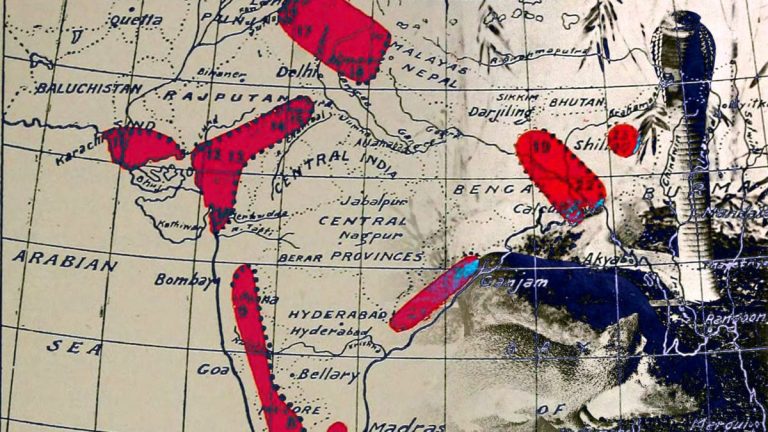

Then, in 1942, Singapore fell to the Japanese, beginning the dissolution of British colonial rule. Japan had defeated British troops in Burma and were pushing their way towards the northeast of India. Over the winter, the British ranks swelled in Karachi as troops traveled to Burma to block the Japanese invasion.

“Are they protecting us?” Narayan asked his father. Raghavan was a civil servant, the Examiner of Local Fund Accounts, and one of the few people in Karachi who could articulate the government’s plans and assess their motives.

“They’re protecting what’s theirs,” his father responded. When Narayan listened to that description of the events he could hear a sound of choking, as though his father didn’t know from which threat to run.

Narayan recalled an afternoon weeks before, in Saddar Town, when he had stood at the periphery of a crowd of British soldiers while a man, surrounded by spectators, unleashed a mongoose and a cobra. The animals lashed at each other and the force of their rage pushed the gasping crowd back. Narayan had seen this fight before, and was drawn less to the bloody display than to the opportunity to study the British in close proximity. His presence there compromised his father’s values, and he was ashamed for sanctioning the brutality of the animals’ battle and the imposing presence of the British. The troops were captivated by the struggle, leaning their lanky bodies closer for a glimpse. Eventually, the battle ended as it always did, the snake’s corpse coiled at the man’s feet.

The soldiers pressed against each other, hands on their comrades’ shoulders, eyes on the battle bloodying the slab of cement in front of them. Through a space in between the two men’s elbows, Narayan saw that the mongoose had returned to its cage. He wondered how well the man had trained the cobra so he himself would not be struck, how unquestioningly the animal must have trusted its captor.

“It’s interesting to them because nobody expects the mongoose to win,” his father later explained. He boxed Narayan’s ears for going to Saddar Town alone without permission, but was willing to discuss the battle’s outcome and the details of where the soldiers had stood.

“But the mongoose always wins,” Narayan said.

“One day it won’t,” his father said.

***

Raghavan, my grandfather and Narayan’s father, had been born in his ancestral village of Adaichani in southern India. His own father, a man with little formal education, had two types of currency: his caste, and the irrigated lands that had sustained his family for decades. He relied on the former to grant his son access to a college education and a career serving the British government, and sold the latter to finance it.

Narayan and his brother Swaminath attended St. Patrick’s School. Their sister Kamala studied at the neighboring St. Joseph’s Convent. Both schools were surrounded by cement walls and patrolled by military police—Indian officers who wore the uniform of the British and followed their command, but had been hired by St. Joseph’s to protect female students from off-duty white soldiers. St. Patrick’s and St. Joseph’s were attended by Indian students clad in British school uniforms. Both were led by Jesuit priests and nuns from France and Germany who believed that adequate piety and devotion could remove the stain of brownness, that the uniform that the children wore gave them entrance to a purgatorial station between native and white.

Coins were scarce at the height of war, and each month Raghavan sent his assistant to purchase containers of the plastic bus tokens that conductors accepted in lieu of currency. There was a flimsy temporariness to them; while Raghavan guarded his money closely, he kept a small box of tokens on his desk for the children to collect on their way to the bus stop. Pressed in their white uniforms, Narayan and his siblings would collect their fare and stand at the stop across the street where the city bus would lead them to the brass gates of their schools.

Narayan understood that wartime scarcity was choking Karachi. But he soon learned that the resources skimmed off of the city could be bundled into rewards for him. One afternoon, as he walked from St. Patrick’s School to the bus, he saw that the vendors that crouched along the road accepted these plastic tokens in exchange for guavas, pomegranates, and palm-sized Kashmiri apples. He reached into his pocket and pulled out his fare, collecting a guava in exchange.

There was a shortcut between St. Patrick’s and Narayan’s home, through the British military campus that housed the soldiers’ firing range. The soldiers left the rear gate unchained for the Indian delivery boys who brought donkeys saddled with large bags of sand and heaved the bags onto piles to be used for target practice. The sound punctuated Narayan’s morning classes.

Dressed in his St. Patrick’s uniform, dusty from the wear of the day, Narayan approached one of the donkeys. He put his hand on its back and pulled it towards him, noting the animal’s easy pliability as he rode it back to Bunder Road. He saw that the donkey’s rear legs were bound loosely by a chain, free enough to walk but too constrained to run away, so he took home one and then another.

Weeks later a neighbor reported Narayan for the thievery. He stood in his doorway, still clad in his uniform, as a low-ranking British soldier gathered the animals. Narayan watched as the donkeys plodded back to the military campus, their chains dragging limply on the ground. The following morning, the sound of rifles carried from the firing range to his Latin class, shaking the air around him.

***

In the summer of 1942, with the city choking from the heat, Narayan learned that Sir William Slim, buffered by American troops, was advancing on the Japanese. Soldiers now arrived in India by the thousands, to acclimate to the heat. They traveled by boat from England to Karachi, an indistinguishable swarm of white faces that crowded the military camps at the edges of the city. It seemed that as soon as one ship left for Burma, two more arrived from England.

Raghavan had learned that the British government intended to evacuate the local population in order to make room for the troops. Heads of families who were integral to the government’s daily functioning would remain in Karachi, while their wives and children were expected to return to their cities and villages.

Narayan had also noticed that there were suddenly fewer brown faces than white ones on the streets of his city, but that fact did not concern him. He was born in his mother’s village in the state of Tamil Nadu, in her childhood house, but had never known or imagined a home besides Karachi. It seemed possible that the war could disrupt their lives temporarily, but Karachi belonged to him and he was doubtful that the British had the power to take that away. (Continues)

_____________________

Sheila Sundar is currently at work on her first novel, set in South India in the 1960s. Her writing has appeared in The Rumpus, The New York Times, The Bookends Review, and elsewhere.

Courtesy: Guernica, an online magazine on global arts and politics.