My father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather spent their entire working lives in the Dutch East Indies, as Indonesia was called until 1945.

By Tulsi Mohinani

Leaving Indonesia

In the late 1950s, Indonesian nationalism was rising but the economy was struggling. Sukarno was president, and foreigners were told that they should either move out of Indonesia or become Indonesians. They had to change their name, their lifestyle and their nationality. Luckily they were not told to change their religion.

My uncles never changed their names, but my eldest uncle, Ghanshamdas, who had a very strong entrepreneurial bent, had gone to Hong Kong to look for further business. When my parents and siblings left Tanjung Pinang to settle in Pune, he wrote to my father, asking him to come to Hong Kong and join him in the business as his partner. My father decided to take up the opportunity. Uncle Ghanshamdas also sent for his eldest son Murli to join him. Murli had not completed his schooling, but was well spoken and mature. He joined his father’s business in Hong Kong and quickly became a good salesman.

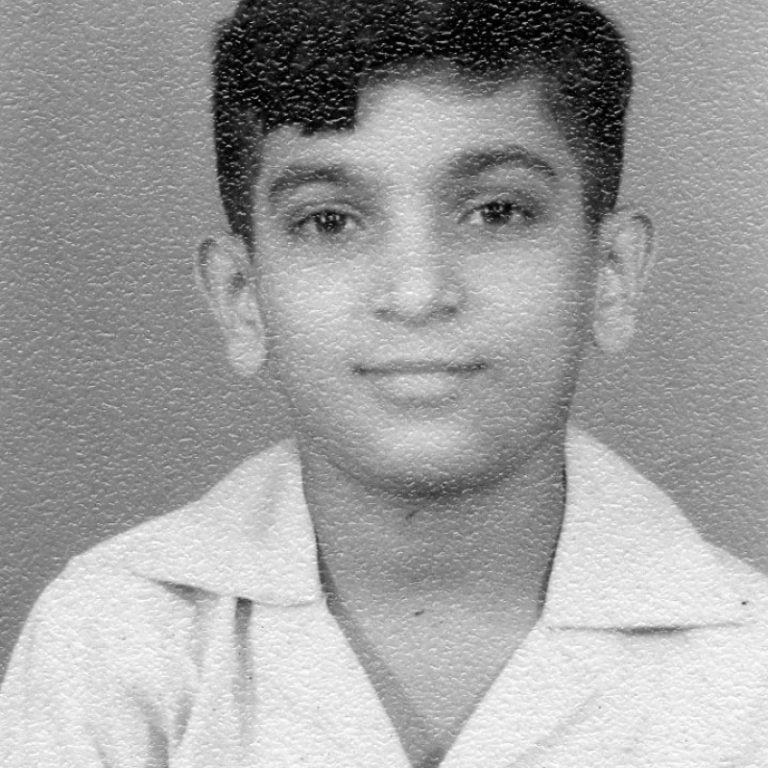

With Murli gone, my routine changed because I was expected to take over his duties working at the shop after school. I was fourteen or fifteen and my work life began with errands and accounting vouchers, and later I was on the sales floor for a little while. It was mostly textiles, which in those days’ people bought by the meter and got tailored. It was a boring life but there was one thing which kept me going. A few blocks from our bungalow was the American Consulate and the United States Information Service (USIS) there had a big library which also screened films. They were documentary movies and mostly propaganda—in those days, soon after the Second World War, the Russians were showing their films, the Chinese had their magazines, and the British had their library and magazines. The USIS library showed their documentary movies daily and free of charge, in a small theatre which could seat 30 or 40 people. I would spend a large part of my holidays watching those movies, which soon had their effect on me. The only thing I wanted was to go and live in the United States.

The power supply to Medan was not sufficient for the city, and area-wise brown-outs meant that alternate nights would be dark. During exam time when we woke early to study, we often did so by candle light or under a gas lamp. In fact, there was nothing to do but study. This is why, when I eventually took my school-leaving examination which came from Cambridge in England, of forty-odd pupils, I was one of only two to pass, the other being a Chinese boy.

After this I worked in the shop for about one year, and then was sent back to India with a six-month stopover in Hong Kong. I was put to work with my father and uncle doing odd jobs but I was 18 and must not have contributed much. They were importing from Japan and selling to shops, so we used to visit shopkeepers and showing them samples of the material and sending them what they had selected the next day. There were both Indian and Chinese shopkeepers, but mostly Indians. In Hong Kong, all ten of us stayed in one apartment. We worked from Monday to Saturday and on Sundays there would be family outings. We did not mix much with others.

By the time I left for India, a coup had taken place in Indonesia and my uncles had sold the house and closed the business. We were not the only family to leave Indonesia. There were many others like us in Bombay and Pune. It was like returning home, another forced exodus similar to what we faced when Pakistan was created. There was a strong feeling that Indonesia was hostile and India would have better opportunities. People started opening businesses, investing in factories. A lot of them failed. Working in India is quite different from working in Indonesia. But my Uncle Ghanshamdas was a visionary. After opening a business in Hong Kong with my father, he also started doing business in Bombay. When my Uncle Lachmandas reached Bombay, there was already a running business. In Indonesia, we ran a textile company and so understood the textile business well. Therefore, in Hong Kong too they opened a textile shop with mostly shirting, which is cloth to make shirts. They imported from Japan and sold to the local people. In India, where local production was good, they bought from factories, and exported to Sri Lanka, which was known then as Ceylon, where they had family members and good business contacts.

When I landed at Bombay, my elder sister Lacha was there to pick me up and we left by train that evening for Pune. It was the first train ride of my life aboard the Deccan Queen and I was going to be reunited with my family after more than seven years.

Pune: The family home

All through my years away, I had missed my family a lot. When I was finally reunited with them, I felt odd and for the first few weeks even addressed my mother as ‘tavha’ which is the Sindhi word for ‘you’ when you address someone with respect.

It was also my first time in India, but India and Indonesia are quite similar, so I wouldn’t say there was a drastic change or culture shock. It was unhygienic, dirty, dusty, people were very friendly and social, there was no privacy—those basic things were all the same. I was at home with my family for six months and the house was always noisy with people constantly visiting, and although I was quite an introvert and did not participate much, I enjoyed the whole thing as an onlooker.

I had always wanted to go to university and study further. But my family found education beyond matric to be pointless, especially for the boys. Some of the girls in our family did go to college, so that they would be occupied until a right match was found for them.

My mother took her duty to get us married very seriously. Each marriage was a project: finding the match, building a relationship with the new in-laws, carrying out all the traditions and sending off the daughters or welcoming the daughters-in-law. She did all these things with wholehearted enthusiasm. My mother loved to arrange marriages. There were also professional women whose business it was to make matches and they would be paid a fee or a piece of jewelry. In our community, the men were usually working overseas and the families lived in Pune or Bombay, which therefore became big centers for matchmaking.

Many of our relatives living in other places would come and stay with us, bringing their eligible sons or daughters and staying on until the right match had been found and the marriage actually took place. We lived in a two-bedroom apartment with one-and-a-half bathrooms, but it was never too small for our relatives. It sounds impossible but there were times when 40 and 50 stayed there together for a wedding. With so many marriages, we had developed a standard format: the engagement would be held in the temple. The sagri, a ceremony in which the groom’s sisters dress the bride and deck her with flowers and jewelry, was held at home, and the satavaro, the party given by the girl’s side after the wedding, would be held in our small living room with home-cooked food. The wedding itself would be held in Kagazwala Hall, where most of the Bhaiband marriages took place. Whether you were rich or middle class, there was only one wedding hall in Pune. Money was spent on jewelry for the bride and on exchange of gifts, but not for pomp and show. Later, of course, this would change.

After I had been at home for six months, my sister Lacha had a job offer for me with her husband’s relatives in Nigeria, and I left on a three-year Sindhwork contract at a salary of 11 pounds per month for the first three years. After that there would be a break of a few months and then on the second musafri it would be 20 pounds.

Nigeria: A taste of the Sindhworki life

The three years I spent in Nigeria gave me good experience. Here too it was a textile business, importing fabric popular in Africa from Japan and selling locally. I started off in the warehouse, moved to the office doing accounts, then correspondence, and then sales, thus gaining an overall exposure. What I learnt in those three years I wouldn’t have learnt working 30 years in my father’s business. It is a different feeling when you work for someone else. The discipline and responsibility is different. Within the family you can take things for granted. Here I would even take work home.

Ours was a small company, but there was a bigger company linked to this and they had a lot of staff whom we used to mix with. At first I was given accommodation in a staff house with three or four others, all between 18 and 25, unmarried, recently out of school, all from India. We were given training and there was an understanding that we would stay till the end of our careers. In Nigeria, the Bhaiband social life was conducted under a strict code: if you were an employee, you would only mix with other employees. Managers would only mix with other managers and bosses would only mix with other bosses. On Saturdays we worked half-day and would mostly go and watch movies, and on Sundays we went to the swimming pool. It was in Lagos that I had my first beer. Malaria was rampant in Nigeria and there was a belief that when you drink alcohol you don’t get malaria! My best friend then was a young man called Madhu. He worked for a company called Gulabani. I have made many efforts to locate Madhu but have not been able to.

After a year or two, business was bad and they downsized. Only two of us were left and the owners moved us to live in a shared room in their bungalow. Coincidentally, the person with whom I worked and shared a room, Ramesh, has a brother called Rajan and it was Rajan’s son Manesh to whom my daughter Priya got married many years later. Among us Sindhworkis, you will always find connections like this.

At the end of the three years, my contract was over. I decided to start my break of six months with a two-week tour of Europe. The first stop from Lagos was always Beirut, so I spent a couple of days there and then went on to London, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, Madrid and Rome with a copy of Europe on $10 a day, a staple of our times, in my hand. It was a wonderful experience.

Back at home in Pune, I was seeing my father and mother together for the first time since leaving home at eleven. My two youngest sisters were still in school and one of my brothers was working in Bombay while his wife lived with us in Pune. In the mornings my sisters and I would just sit and look out of the window, watching people pass by. It was a relaxing, enjoyable time. As it came to an end, I started waiting for my boss in Nigeria to call me back. After a few weeks of looking out for a letter with a ticket in it, we started waiting for the postman every morning, calling out to him, ‘Is there any letter from Nigeria?’ But nothing came.

Hong Kong: Growing a family business

My father had come back home from Hong Kong because his stepbrother had terminated their partnership. He was at a loss about what to do next. With eleven children, some still quite young and some girls for whom he would have to provide dowries, he was quite depressed. He wrote to his brother asking for a better settlement and eventually my Uncle Ghanshamdas replied, offering that if he returned to Hong Kong and opened his own business, he would help by supplying him goods.

So in March 1969, my brother Haresh and I went with our father to Hong Kong to open our own business Mulitex, named after my mother Muli. We rented a store on Stanley Street and put up a partition for our personal belongings and folding aluminum beds. At night we would open up the beds and sleep among the bales of textiles, takias as they are called. In the morning we would fold them back, so that everything was like a shop again. We didn’t have much money, but my uncle was generous enough to give us samples and when we received an order, he supplied us with the goods. We would set out every afternoon after lunch, visit potential customers and try to sell. Next day we would spend the morning cutting the pieces and packing them and carrying them out to the transport people. It was a very small wholesale business where retailers would buy 10 or 15 yards and the big orders were 60 yards and 100 yards, but never very much. It was a hard life but for me a wonderful experience living like that and working so closely with my brother and father. (Continues)

________________

Courtesy: Sahapedia

Click here for Part-I