Gul Muhammad Khatri was a renowned artist, but his art could earn only the name and fame for him unlike certain other artists who enjoyed luxurious life

Nasir Aijaz

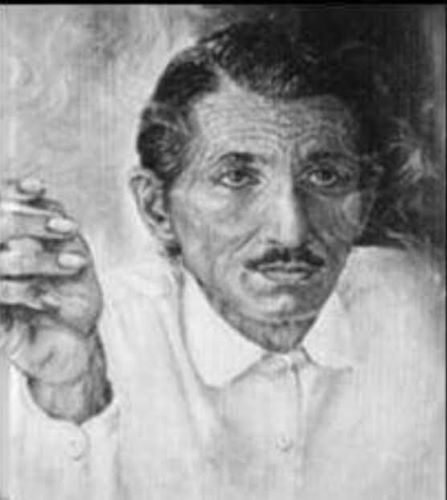

Slim and tall, having dark complexion, Gul Muhammad Khatri often used to drop in at my newspaper office in Karachi during second half of 1970s. His small studio shop was located in Lea Market, downtown area, from where he would walk to the historic ‘Bank of India’ building at Bandar Road, which housed the office of Sindhi Daily Hilal-e-Pakistan besides some offices of lawyers. Gul was a renowned artist, but his art could earn only the name and fame for him unlike certain other artists who enjoyed luxurious life developing contacts through their ‘talent’, which he had not. Although, then Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto personally knew him but he never benefited from it.

Born in 1919, Gul Muhammad Khatri had produced art works in the form of portraits, landscape art, and calligraphic illustrations of Sufi poetry, especially poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai. He also did commercial art work in the form of poster design, glass painting, sign boards, textile design, theatrical design, cinema posters, tile design as well as Sindhi, Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati and English calligraphy.

Due to his lifelong interest in the art of the Indus Valley, he was known as Mussawar-e-Latif and Founder of the Indus Art

Khatri was also a prolific writer, authoring many articles and essays on Pakistani and Indus art and literature in Sindhi and Urdu languages, which were published in different newspapers and periodicals. Due to his lifelong interest in the art of the Indus Valley, he was known as Mussawar-e-Latif and Founder of the Indus Art.

He learned art from his teacher Charanjit Singh Wordi under whose mentorship he studied for about 12 years. In 1967, Khatri founded Mehran Cultural Association to develop Indus art and literature and was elected its President.

Ordeal of an artist

It was some time in 1976 when we first met – the year I had joined the field of journalism. Although we were new for each other but perhaps he found a person in me to share the stories of his plight. Gul often used to say, “Nobody has done good to me, but I will not blame anyone.” But I could feel the pain hidden in his words. He was not happy with treatment meted out to him by various government departments and institutions.

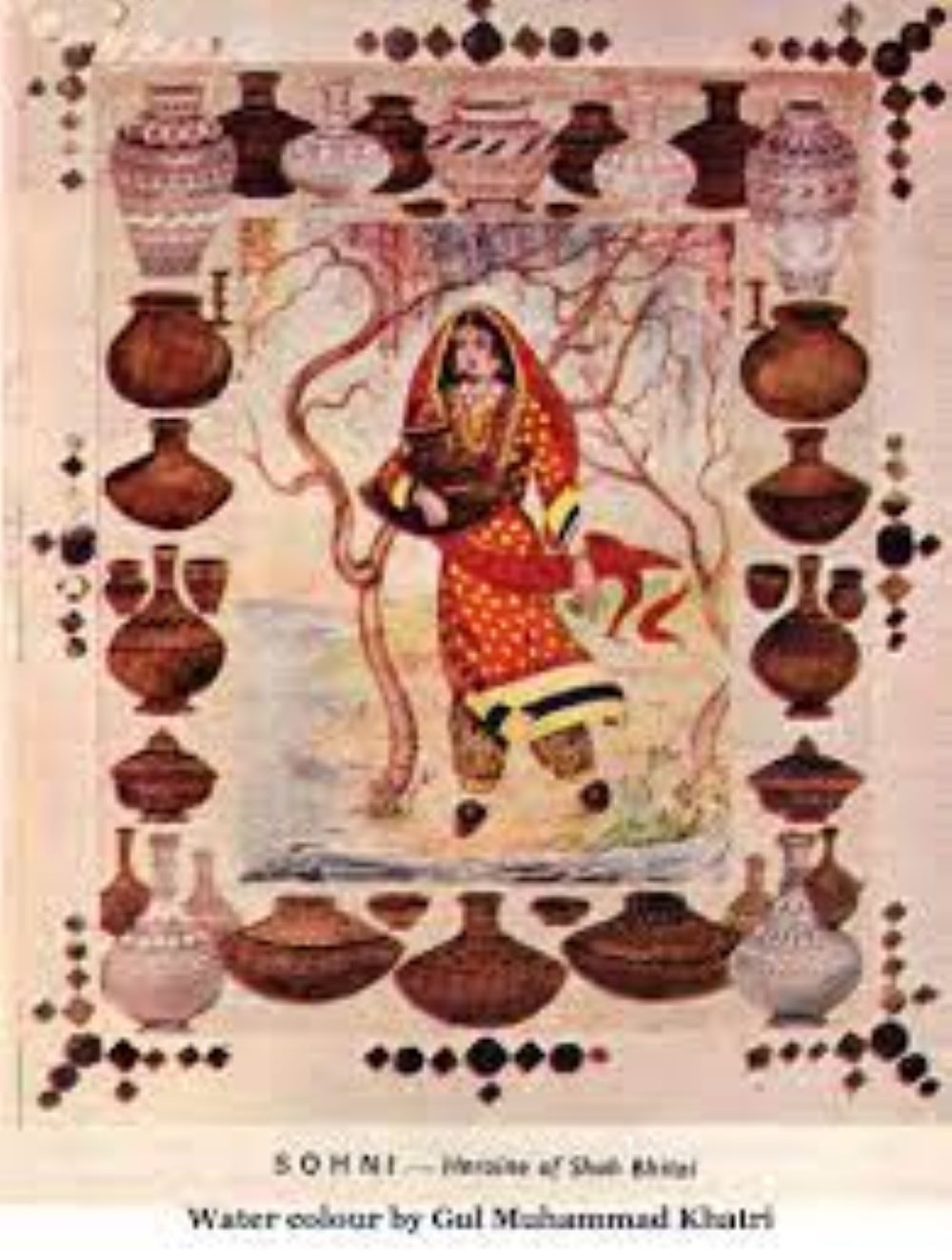

Gul Muhammad Khatri blamed none, for he was a simple and humble, but being very straight-forward he never tried to hide what he had been suffering all his life. He was not happy with the people at the helms of affairs in Sindh Culture Department, who always ignored his work. “I handed them manuscript of ‘Naqoosh-e-Latif’, the translation of Sindh’s great mystic poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s poetry in Urdu, English, Gujarati and Hindi languages along with the illustrations, but with no response,” he used to tell me showing the illustrations of Seven Queens, the heroines of Bhittai’s poetry, he had beautifully painted.

None of the government institutions including Pakistan Television, Radio Pakistan, Institute of Sindhology, Sindhi Adabi Board, Mehran Arts Council Hyderabad and Pakistan Arts Council Karachi did pay any importance to him and his work.

I handed the manuscript of ‘Naqoosh-e-Latif’, the translation of Sindh’s great mystic poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s poetry in Urdu, English, Gujarati and Hindi languages along with the illustrations, to Sindh Culture Department but with no response

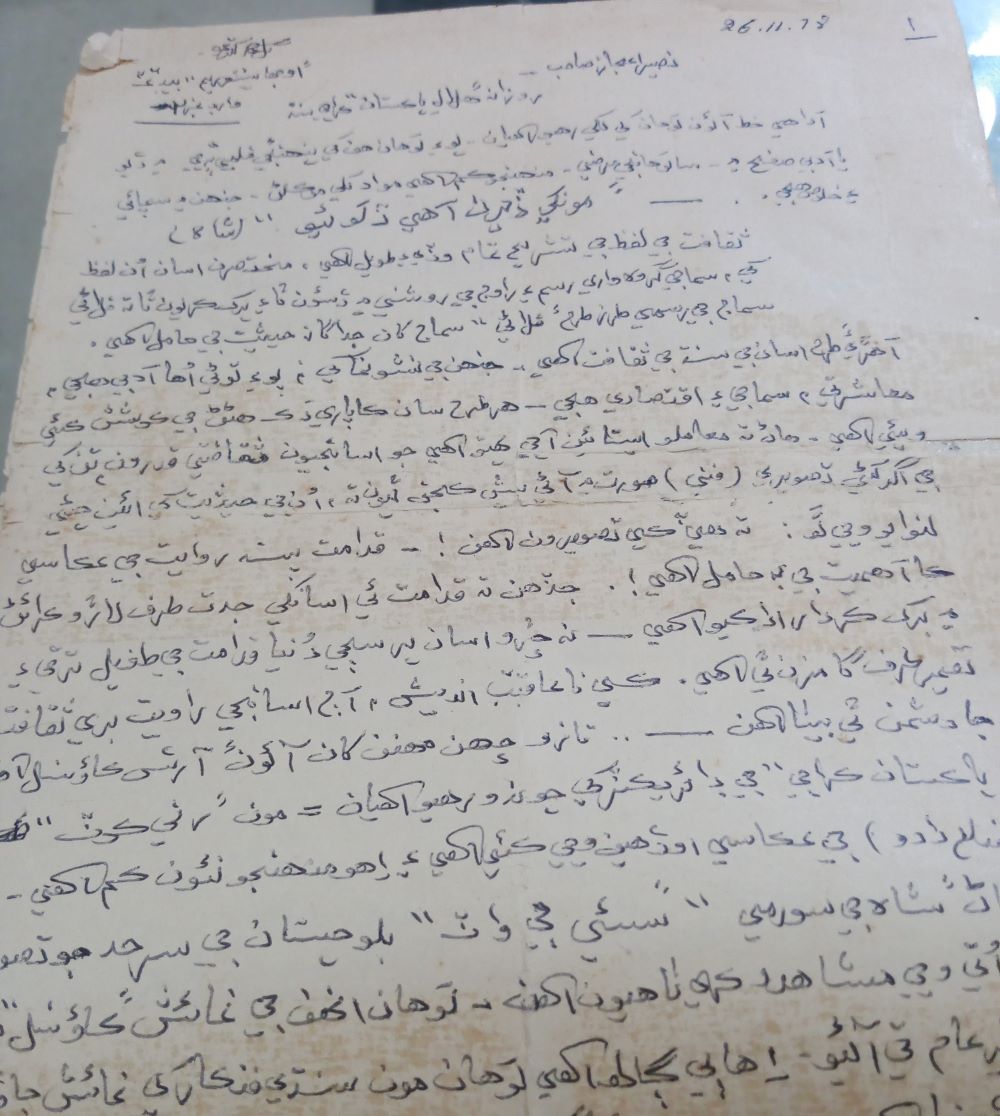

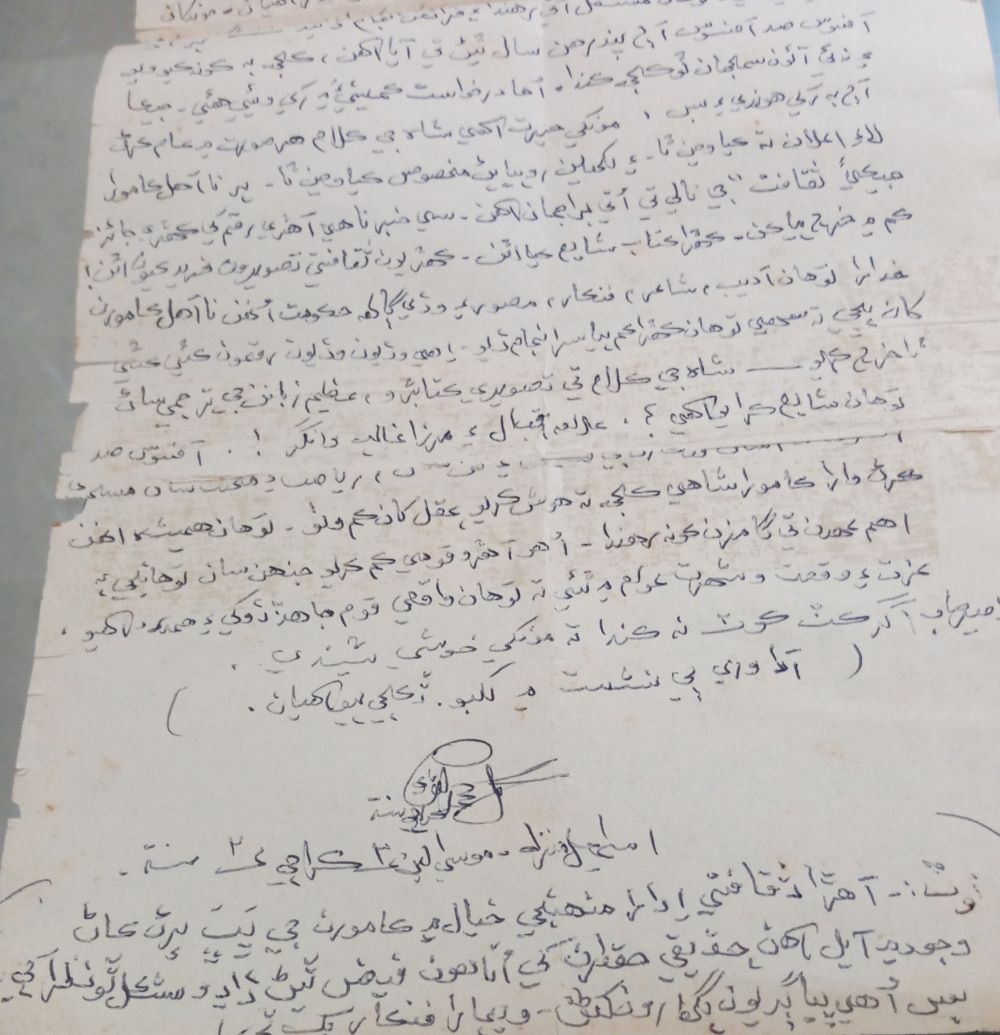

In 1978, Khatri, a chronic patient of Tuberculosis, which proved fatal for him, was admitted at Ojha Sanatorium, where he previously had been for treatment. During last days of his life, Khatri wrote three letters to me from the hospital bed. I received his first letter in March 1978, second in October and the last one in November same year. When I received his first letter, I imagined a feeble and unattended artist lying in a hospital bed, and published his letter in Daily Hilal-e-Pakistan with my comment: “An outstanding artist of Sindh, who translated great poet Bhittai’s Risalo with paintings, has again been admitted to hospital and alas neither the Culture Department of Sindh nor any other institution has cared. Physically he is still alive but can anyone feel his spiritual pain? I am sure, we will declare him a National Artist and observe anniversaries when he will be no more with us, because we are a nation ‘Idolizer of the Dead’. We always wait for the death of our artists and writers.”

I would like to quote a few lines from his first two letters for the readers, which show apathetic attitude of institutions towards a great artist.

“The Kings of Pakistan Television got colored slides from me. One and half a year has passed but neither they returned nor presented the same in any program despite having signed a contract form.”

“My own people (Sindhis) have neglected me but I continue to depict Sindhi culture in my paintings and dump it to be eaten away by the rats. So far paintings worth thousands of rupees have destroyed, and I am sure the entire assets will get ruined as none of the institution will take measures to save it. Even the Director of Sindh Culture Department is not willing to publish my work – paintings with translation of Bhittai’s poetry in five languages.”

“I had requested the management of Mehran Arts Council Hyderabad to provide me with a room where I could work for the Council as well as for my livelihood, but alas an artist could not get a small space at the Council, spread over a vast land.”

“The Management of Mehran Arts Council once said, ‘We are setting up a Khatri Corner. I gave them eleven precious paintings, but neither they established any Corner nor returned the paintings.”

“Karachi Arts Council provided Sadqain with a free space. He was honored with title of National Artist. They also established an Institute of Arts to engage the artists. But I am deprived of such facilities, being a Sindhi, although, I am member of Karachi Arts Council.”

Now I would come to the last letter of Gul Muhammad Khatri, which he wrote from Bed No: 4, Ward No: 2 of Ojha Sanatorium Karachi, and is preserved in my personal collection. I consider the 4-page hand-written letter of about 2000 words in Sindhi language, a ‘White Paper’ on the indifferent and biased attitude of institutions and individuals towards a marvelous artist of Sindh.

Here are some excerpts of the letter dated November 26, 1978 that begins with a line from a verse of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai – مونکي ڏيرن آھي ڏکوئيو which literally means that ‘He has been suffering at the hands of his own people’.

Highlighting the importance of culture and heritage of Sindh, Gul Muhammad Khatri shares about his work on historic Ranikot Fort, spread over 24 miles in Khirthar Mountain Range, known as Great Wall of Sindh, and the path of Sasui (One of the seven heroines of Bhittai), she had taken to meet her beloved Punhoon. “I had worked on these paintings spending several days at Ranikot and visiting the difficult mountainous regions from Sindh to Balochistan. It was a unique work none had labored so far,” he writes adding, “For six months, I had been wandering to convince the Director of Karachi Arts Council to organize an exhibition. I had no greed of earning some money, as I knew that they don’t pay to any artist. I just wanted exposure of my hard work and draw attention of domestic as well as foreign tourists to the neglected heritage of Sindh. This would, in turn, result in development of approach roads to the fort, generate revenue for the government and job opportunities for the local people.”

Khatri was the first artist to visit historic Ranikot and portray it in his paintings

“But, I was not surprised on the response of biased Director of Karachi Arts Council, who every time repeated the same single sentence – ‘Khatri, we will let you know about exhibition date by the post. Don’t bother to visit Arts Council’. Four to five months passed, during which several exhibitions were held. I once again approached him to know if they have any objection, but I received same response ‘We have already told you – We will let you know.’”

“These people are enemies of culture and heritage. We must not expect good from them. They are working for their own interests. They are spending huge funds on promotion of their own people.”

“Even the National Council of Arts Islamabad, established 15 years back, has never invited me, a representative artist of Sindh, during this long period,” Khatri writes.

“Interestingly, they write letters to me for donating the paintings whenever they plan to organize charity programs for the help of flood-affected people or others. I never refused them and took active part in such activities and donated my paintings. On the contrary, they too avoided to hold exhibition of my paintings because they never wanted to introduce Sindhi culture and heritage to the world through the universal language of colors and paintings.”

Khatri also visited mountainous areas of Sindh and Balochistan and portrayed the Sasui’s path she traveled to meet Punhoon

Khatri also visited mountainous areas of Sindh and Balochistan and portrayed the Sasui’s path she traveled to meet Punhoon

“Dear Nasir, even while lying here in hospital, my mind continues agitating. I want to write against the injustices. I feel tired as the letter has become too lengthy. I will write more in my next letter, but before ending here, I would like to share what our own people have done.”

“In 1965, when Dr. Nabi Bux Baloch was the honorary Secretary of Bhit Shah Cultural Center Committee, he offered me to work on frescoes, translate the Bhittai’s poetry in murals besides imparting training to the aspiring artists at Bhit Shah. I was told that a bungalow will be allocated to me for this purpose. On his instructions, I submitted an application but never got any response during one and half a decade.”

“Again, I am not surprised on such attitude, as the seats at the Culture Department are occupied by the corrupt and inefficient persons. They are drawing big salaries and enjoying luxurious life while the poor artists are starving.”

In a small note on back of the letter, Gul Muhammad Khatri wrote, “Please ask Umerdin Bedar (a journalist friend) to send him a required injection. And also ask Mumtaz Mahar (a writer) to visit my home (located in Moosa Lane Lyari), as nobody has come to see me since long. I also need warm clothes and some money.”

I couldn’t control my tears rolling down while quoting last words of his last letter.

He couldn’t write more letters, as his condition had deteriorated during next few months, when he breathed his last on March 20, 1979.

Neglected in Life, Forgotten after Demise

Gul Muhammad Khatri was neglected during life and remains forgotten even after he passed away. The concerned government department or any institution never tried to collect and preserve his work, or to set up any Corner to honor ‘Mussawar-e-Latif’. Once, his friend Muhammad Siddique Kaka and his son Afzal Khatri organized an exhibition at Arts Council a few decades back and then there is complete silence. He remains forgotten even on his death anniversary.

It was only in 2010, when Gul Muhammad Khatri was posthumously honored with a special shield in acknowledgement of his services to Sindh Art at a seminar organized by the Institute of Art and Design University of Sindh.

In 2017, Zafar Kazmi Institute for Art & Literature produced a documentary on the life and works of Gul Muhammad Khatri and remembered him as the ‘Pride of Mehran’.

_________________

Nasir Aijaz is a Karachi-based senior journalist and author of nine books on literature, language and history. He can be accessed at nasir.akhund1954@gmail.com