Prime Minister Modi raked up a six-decade-old debate on decisions taken by Jawaharlal Nehru in the final years of Portuguese rule to accuse the Congress of apathy towards Goa and Goans.

By Professor Rahul Tripathi

With Goa going to polls (Election was held on Monday Feb 14, 2022), it was time for politics to confront history again, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi had set the tone.

“Goa was liberated 15 years after India attained freedom. Pandit [Jawaharlal] Nehru felt that if he launched a military operation to oust the colonial rulers from Goa, his image as a global leader of peace would be impacted,” he said in Rajya Sabha on February 8.

Modi quoted from Nehru’s 1955 Independence Day speech, holding the nation’s first Prime Minister guilty of leaving satyagrahis in the lurch, refusing to send the Indian Army to liberate Goa, even after 25 of them were shot dead by the Portuguese Army on the Goa Maharashtra border.

The following day, Home Minister Amit Shah and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh said in campaign speeches that if he wanted, Nehru could have liberated Goa in 1947 itself, and local BJP units circulated social media posts amplifying the message.

On Thursday, the Prime Minister during a brief campaign in Goa repeated his attack on Nehru, painting him and the Congress as callous and uncaring in their attitude towards the state and its people.

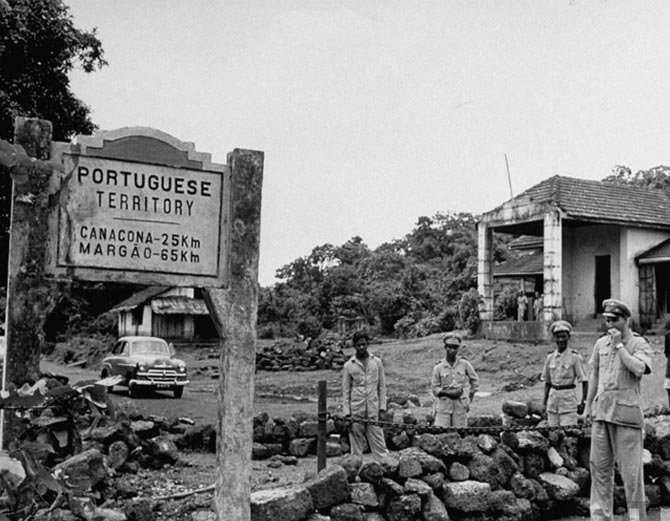

Goa became a Portuguese colony in 1510, when Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque defeated the forces of the sultan of Bjiapur, Yusuf Adil Shah. The next four and a half centuries saw one of Asia’s longest colonial encounters — Goa found itself at the intersection of competing regional and global powers and religious and cultural ferment that would lead eventually to the germination of a distinct Goan identity that continues to be a source of contestation even today.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Goa had started to witness an upsurge of nationalist sentiment opposed to Portugal’s colonial rule, in sync with the anti-British nationalist movement in the rest of India. Stalwarts such Tristão de Bragança Cunha, celebrated as the father of Goan nationalism, founded the Goa National Congress at the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress in 1928. In 1946, the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia led a historic rally in Goa that gave a call for civil liberties and freedom, and eventual integration with India, which became a watershed moment in Goa’s freedom struggle.

At the same time, there was a thinking that civil liberties could not be won by peaceful methods, and a more aggressive armed struggle was needed. This was the view of the Azad Gomantak Dal (AGD), whose co-founder Prabhakar Sinari is one of the few freedom fighters still living today.

As India moved towards independence, however, it became clear that Goa would not be free any time soon, because of a variety of complex factors. The trauma of Partition and the massive rupture that followed, coupled with the war with Pakistan, kept the Government of India from opening another front in which the international community could get involved. Besides, it was Gandhi’s opinion that a lot of groundwork was still needed in Goa to raise the consciousness of the people, and the diverse political voices emerging within should be brought under a common umbrella first.

There were also questions with regard to the mode of protest to be followed. In her thesis ‘Goa’s Struggle for Freedom, 1946-61: The Contribution of National Congress Goa and Azad Gomantak Dal’, historian Dr Seema Risbud highlighted the dichotomies within the groups fighting for freedom in Goa, and argued that satyagraha had its limitations against a totalitarian regime. This point appears to have been validated by the success of the militant role played by the AGD in the liberation of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, another Portuguese enclave (albeit with the covert support of Indian authorities, as some have suggested).

It was apparent that Nehru was prepared for the long haul in Goa, perhaps trying to exhaust all options available to him given the circumstances that India was emerging from, and where he was headed in shaping India’s position in the comity of nations. Portugal had changed its constitution in 1951 to claim Goa not as a colonial possession, but as an overseas province. The move was apparently aimed at making Goa a part of the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military alliance — so the collective security clause of the treaty would be triggered in the event of an attack by India or any other nation — but this was not acceptable to other NATO member countries.

It was apparent that Nehru was prepared for the long haul in Goa, perhaps trying to exhaust all options available to him given the circumstances that India was emerging from, and where he was headed in shaping India’s position in the comity of nations. Portugal had changed its constitution in 1951 to claim Goa not as a colonial possession, but as an overseas province. The move was apparently aimed at making Goa a part of the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military alliance — so the collective security clause of the treaty would be triggered in the event of an attack by India or any other nation — but this was not acceptable to other NATO member countries.

Nehru saw it prudent to pursue bilateral diplomatic measures with Portugal to negotiate a peaceful transfer while, at the same time, a more ‘overt’ indigenous push for liberation — one that would strengthen India’s moral argument — gathered momentum. His 1955 Independence Day speech — cited by Modi in Rajya Sabha — criticizing the satyagrahis who were trying to cross the border did demoralize the diverse pan India group of liberation fighters comprising socialists, communists, and the RSS. But the firing incident also provoked a sharp response from the Government of India, which snapped diplomatic and consular ties with Portugal in 1955.

The obvious question that arises is, if things had reached such a stage in 1955, why did Nehru wait until December 1961 to launch a full-scale military offensive, even though India continued to raise the issue of Goa at various levels and fora?

D P Singhal, who was a political scientist at the University of Queensland at the time, provided a clue in his paper ‘Goa: End of An Epoch’, published in The Australian Quarterly in March 1962. With India firmly established as a leader of the Non Aligned World and Afro Asian Unity, with decolonization and anti-imperialism as the pillars of its policy, it could no longer be seen to delay the liberation of Goa. An Indian Council of Africa seminar on Portuguese colonies organized in October 1961 heard strong views from African delegates who argued that India’s policy of going slow on the Goa question was hampering their own struggles against the ruthless Portuguese regime. The delegates were certain that the Portuguese empire would collapse the day Goa was liberated.

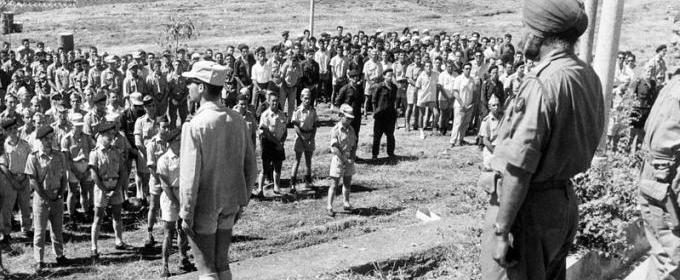

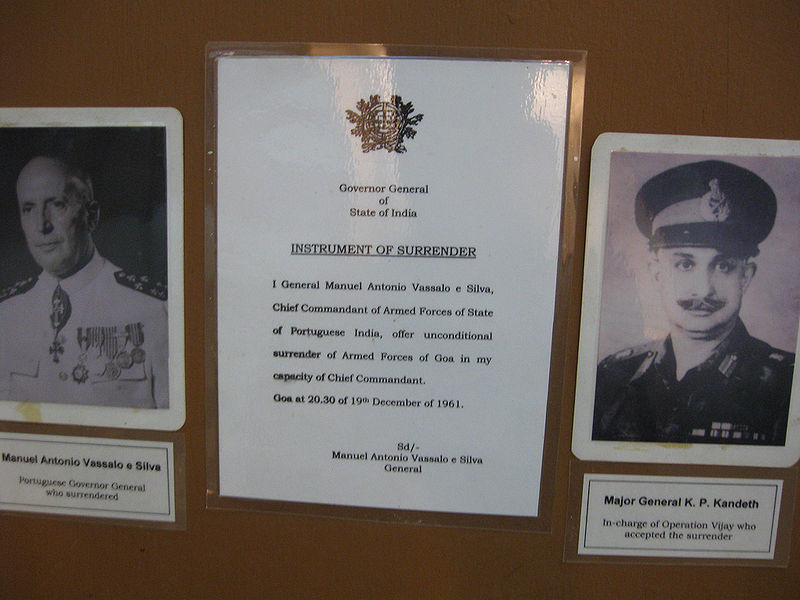

The rest, as they say, is history. Goa was liberated on December 19, 1961 by swift Indian military action that lasted less than two days.

The debate in 2022

Politics needs to be charitable to history, because at some point it would be put to the same scrutiny and judgment as it becomes history itself.

Sinari, the lone surviving member of the AGD, whose sense of history and political instincts have not been blunted by age and failing health, says attempts at political point-scoring around incidents that took place in a certain historical context more than six decades ago, only diverts attention and focus from pressing current issues.

Goa has seen 60 years of eventful liberation and successful amalgamation in the Indian Union. It is more important for it to look ahead to its future than to rapidly receding, increasingly dim images in the rear-view mirror.

____________________

Prof Rahul Tripathi teaches Political Science at Goa University. Views expressed are personal.

Courtesy: Indian Express

Photo Courtesy: Pazhayathu and The World Under-Reported