In the Karachi interview, the Pir was asked about Gen. Zia. Personally, the Pir said, he did not much care for the general. “We have a strictly business relationship,” he had said.

A historic article based on interview of Shah Mardan Shah Pir Pagara-VII that also analyzes the feudal society of Pakistan in general and Sindh in particular. The article was published 36-years back in Los Angeles Times newspaper.

BY RONE TEMPEST

PIR JO GOTH, Pakistan

When Prime Minister Mohammed Khan Junejo comes to this village to visit his spiritual master, the Pir of Pagaro, he must sleep on the ground. His head may never be raised above that of the man he worships as the “visible symbol of Allah.”

Like all of the followers of this pir, one of the most powerful of the several hundred hereditary rulers, living saints and feudal landlords in Pakistan, he must greet his master with an obsequious bow that ends with his forehead touching the ground in front of his master’s feet.

If the pir–the word means “spiritual guide” in Sindhi, the local language–sits on a chair, the prime minister must sit on the floor. He must never wear shoes in the pir’s presence. And if the pir asks him to perform any task, no matter how loathsome or dangerous, Junejo must do it unhesitatingly. That is the law of the Brotherhood of the Pir of Pagaro.

Practiced Only in Village

In practice, this kind of slavish devotion is reserved for this village near the Indus River, where the main mosque and shrine of the followers of the Pir of Pagaro are situated. There is no bowing and scraping by the prime minister in the National Assembly, where both men are members. As the Pir of Pagaro, 58-year-old Sikander Ali Shah, explained in a recent interview: “When he comes to my house, he is my follower. When I go to his office, I go to see the prime minister.”

Pakistan is a place where one man’s serf is another man’s master. Junejo himself is a wadera, or feudal landlord, in the Sanghar district of Sindh province, the southern state that straddles the Indus. There, he has his own followers and subjects.

Democratic institutions have never taken root as they have in neighboring India. Life in Pakistan continues to be dominated by feudal, tribal and religious orders.

Along Family Lines

For example, when Junejo ordered the arrest of opposition leader Benazir Bhutto in Karachi on Aug. 14, demonstrations for and against the arrest followed traditional feudal and family lines in Sind province.

Followers of the pir, in their strongholds near Sukkur and in the Sanghar district, supported the government. On several occasions, they attacked Bhutto’s supporters with axes. During most of the weeklong disturbances, in which as many as 29 people died, the pir’s men acted as a paramilitary force on the side of police and the army.

Bhutto, meanwhile, gained strong support from the right bank of the Indus River near Larkana, site of her own family’s feudal homestead. The most violent demonstrations on her behalf took place in Hala, north of Hyderabad, where she has the support of another traditional ruler, the Makhdun of Hala, a powerful rival of the Pir of Pagaro.

The president of Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party in Sindh is Khalique Zaman, son of the Makhdun of Hala.

“Benazir likes to present herself as the beacon of democracy, yet she draws on the same traditional power bases as the other politicians,” Hamida Khurro, a political scientist in Karachi, said.

One experienced political officer at a Western embassy said:

“Pakistan is a very conservative country whose rural traditions have changed the least in all of South Asia. It is a country where great landlords and traditional religious leaders exercise considerable influence and hold large percentages of the wealth.

Factor in Politics

“Politics in this country cannot be understood independently of how these people choose to exercise their influence and interact with each other. It is a throwback to the politics of a century or more ago in other parts of the world.”

Obedience to some traditional ruler or tribal chieftain is common in most of Pakistan. Only in the relatively affluent, well-educated, urban centers of Punjab province such as Lahore and Rawalpindi is the phenomenon of the independent voter a significant factor in Pakistan political life.

Pakistanis who live in the rugged desert province of Baluchistan usually owe fealty to their tribal chiefs, the sardars. In the untamed North-West Frontier Province on the border with Afghanistan, it is the fiercest of all the tribal leaders, the ruthless khans, who hold sway. But it is in the rural reaches of steamy Sind province, the land that hugs the Indus River on its route to the Arabian Sea, where the traditional social orders seem most pervasive and cruel.

Can Dictate Marriage

A poor man here in Sindh province may drive a tractor. But he remains a virtual slave to the powerful feudal landlords, the waderas, who still thrive here. The wadera may tell the man whom he may marry and even dictate the names of his children. He may beat the man or even kill him.

Prime Minister Junejo, named to his office in 1985 after nearly eight years of martial law, is one of the best examples of a man straddling the ancient and modern orders of Pakistan.

Although ultimate power in Pakistan still rests with President Zia ul-Haq, who took over in a military coup in 1977, Junejo has gradually assumed more responsibility, particularly after Zia lifted martial law last December.

But while his ascent has raised hopes for a return to democratic rule here, it has also enhanced the status of more traditional forces, such as those of Junejo’s spiritual and temporal lord, the enigmatic Pir of Pagaro.

Lord of the Hat

The burly, handsome pir–his full title means Lord of the Hat, a reference to the tall, knitted hat that he wears when enforcing discipline–is the most powerful and most feared of all the waderas. And he makes no secret of his ambition to extend that power, to convert millions more to his flock and rule all of Pakistan.

His first obligation, the pir said in an interview at his Karachi home, is to “serve the followers of the shrine.” After that, he said, “I want to rule all Pakistan and even a little bit more.”

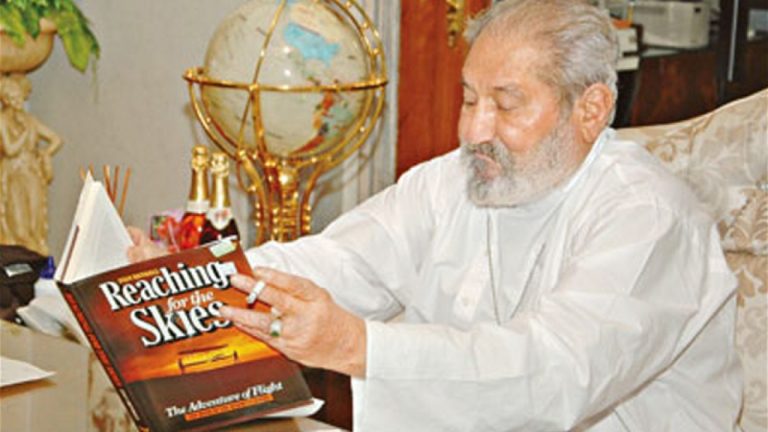

As he talked, the pir smoked a cigarette in a long elegant holder. He wore two rings, each with five large stones, all diamonds except for a sparkling blue sapphire. A gold chain around his neck supported a large pendant, with a verse from the Koran written in smaller diamonds.

The pir, whose interests besides politics include caged birds, tropical fish, horse racing and computers, usually speaks in epigrams and riddles.

Months ago, when he was first asked about his relationship with Junejo, he said he had “loaned” him to the Pakistan government. In the recent interview, the pir smiled and added, “Now the loan has become an investment.”

Ready to Give Lives

True followers of the pir are prepared to sacrifice their lives at any time for their lord. To refuse his command is unthinkable. In the mind of a true believer, therefore, it is not Junejo who presides over Pakistan.

Ghulam Shabbir, a Muslim historian who lives in Pir Jo Goth, said, “Mohammed Khan Junejo is Pir Sahib’s follower. In that sense, you can say it is Pir Sahib’s government.”

To the pir’s followers, this poses no problem for the people of Pakistan. “The interests of Pir Sahib and the interests of Pakistan are the same, so there is no conflict,” said Mufti Mohammed Rahim, a religious leader and follower of the pir.

The current pir is the eighth hereditary ruler of more than 900,000 devotees who consider him a living extension of God.

The tradition of pirs in Islam dates to the 12th-Century movement of Sufism, in which mystical practices, some taken from Hinduism and Buddhism, were introduced in Islamic society. Like the Buddhist bodhisattva, the Muslim pir, or murshid (preceptor), is thought to have obtained spiritual enlightenment while on earth. Although the principal tenet of Islam is “There is no God but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet,” many of the pirs are worshiped by their followers as earthly manifestations of God.

Some in Army, Police

At least 50,000 of the Pir of Pagaro’s most fanatical followers, the militant hurs, serve in positions reserved for them in the Pakistani army and provincial police. The jobs were created as a reward to the pir for his service to the several military governments of Pakistan, including Gen. Zia’s eight-year military regime.

When a reporter arrived at the guest house of the pir in Pir Jo Goth village recently, he found several of the pir’s administrative officials, called kaliphs, sitting in the rose garden with senior Pakistan police officials. In front of them stood 200 young men, all followers of the pir, who had been chosen for induction into the provincial police as part of the pir’s quota.

In the Karachi interview, the pir was asked about Gen. Zia. Personally, the pir said, he did not much care for the general.

“We have a strictly business relationship,” he said.

In effect, the police and military forces allotted to the pir constitute a private army at his disposal. Occasionally, they have been used against his political opponents, most recently against supporters of Benazir Bhutto. The soldiers and police are also a major source of income for the pir, since all followers must pay him a tithe.

A Rich Landlord

The pir is also a rich landlord. He owns groves of date palms, cotton fields and rice paddies here in the irrigated Indus valley.

He is a leader and former president of the ruling party, the Muslim League. He is a senator in the Pakistan National Assembly and his eldest son, the next pir, is the minister of power and irrigation for Sind province, the official who decides who receives water in a region where water represents riches and power. Another son is a member of the National Assembly.

A previous pir, the grandfather of the incumbent, once demonstrated his absolute authority to horrified British visitors by ordering several followers to jump to their death from towers in his royal compound.

He later led his most fanatical followers, the hurs, in a bloody revolt against the British. As a result, the British labeled the hurs a “criminal tribe,” a designation they had in common with the thughis of Bengal, from whom came the word “thug.”

Relocated by British

The hurs were required to register with local police, and in an effort to disband them the British relocated many of them to other parts of their empire. Many hurs were deposited on the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean, where their descendants remain today.

Hur means free man in the local language. The hurs believe that their pir has “freed them” from this life and ensured their place in heaven. Their devotion equals that of the fabled hashishis who followed Iranian folk leader Hasan Sabbah and from whom comes the word assassin.

The current pir’s father, Pir Sibghatullah Shah (1908-1943), also battled the British, this time as part of the Indian Freedom Movement in the territory that now includes Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. That pir hated the British after they jailed him for keeping a young boy in a cage in front of his castle in Pir Jo Goth.

In jail on that charge, the pir met Hindu freedom fighters from Indian Bengal and decided to launch a terrorist campaign against the British.

In 1943, Sibghatullah Shah was hanged by the British for “conspiracy to wage war against the king.” Hundreds of his followers were also hanged, many without trial.

Herded Into Camps

Other hurs and their families were herded behind the barbed wire of concentration camps where they were kept for many years, even after Pakistan became independent in 1947.

The current pir is more law abiding. While his father was in jail, the British dynamited the castle here and sent him and his brothers off to boarding school in England. Pictures of the young pir in his English school cricket jacket are on display in his rebuilt castle.

The castle has a long balcony facing an open courtyard where the pir, like a South Asian pope, makes appearances and delivers homilies to throngs of followers who come to see him and the shrine containing the coffins of his ancestors.

After returning from England in 1952, Sikander Shah was crowned Pir of Pagaro in an elaborate ceremony at Pir Jo Goth. In 1965, he gained favor with the Pakistan government by ordering his fanatical hurs to the front in the war against India.

“Now I give you to the command of the Pakistan army. Obey their command whatever it may be,” the pir told them as they assembled in the courtyard of his castle here.

Chanting “Hail to the Pagaro,” the hurs marched to battle in their white turbans and traditional blue shawls called ajraks. Although poorly armed, they distinguished themselves in battle, particularly in the tricky desert region of Rajasthan.

When the Indian army heard their chants, boasted historian Ghulam Shabbir in an unpublished essay on the 1965 war, their commanders reportedly said: “The white turbaned ones have turned up; flee, therefore.”

Since that time, said the pir, the visible symbol of Allah, the creator and sustainer of all the worlds, the direct representative of the Holy Prophet of Islam, he has supported whomever has had the support of the army in Pakistan politics.

“I am the GHQ (general headquarters) man,” he said.

___________________

Courtesy: Los Angeles Times – Published on September 25, 1986