Kanu had vivid memories of his childhood in Sindh. One of the most striking is of the love and cordiality between the Muslims and Hindus

Saaz Aggarwal

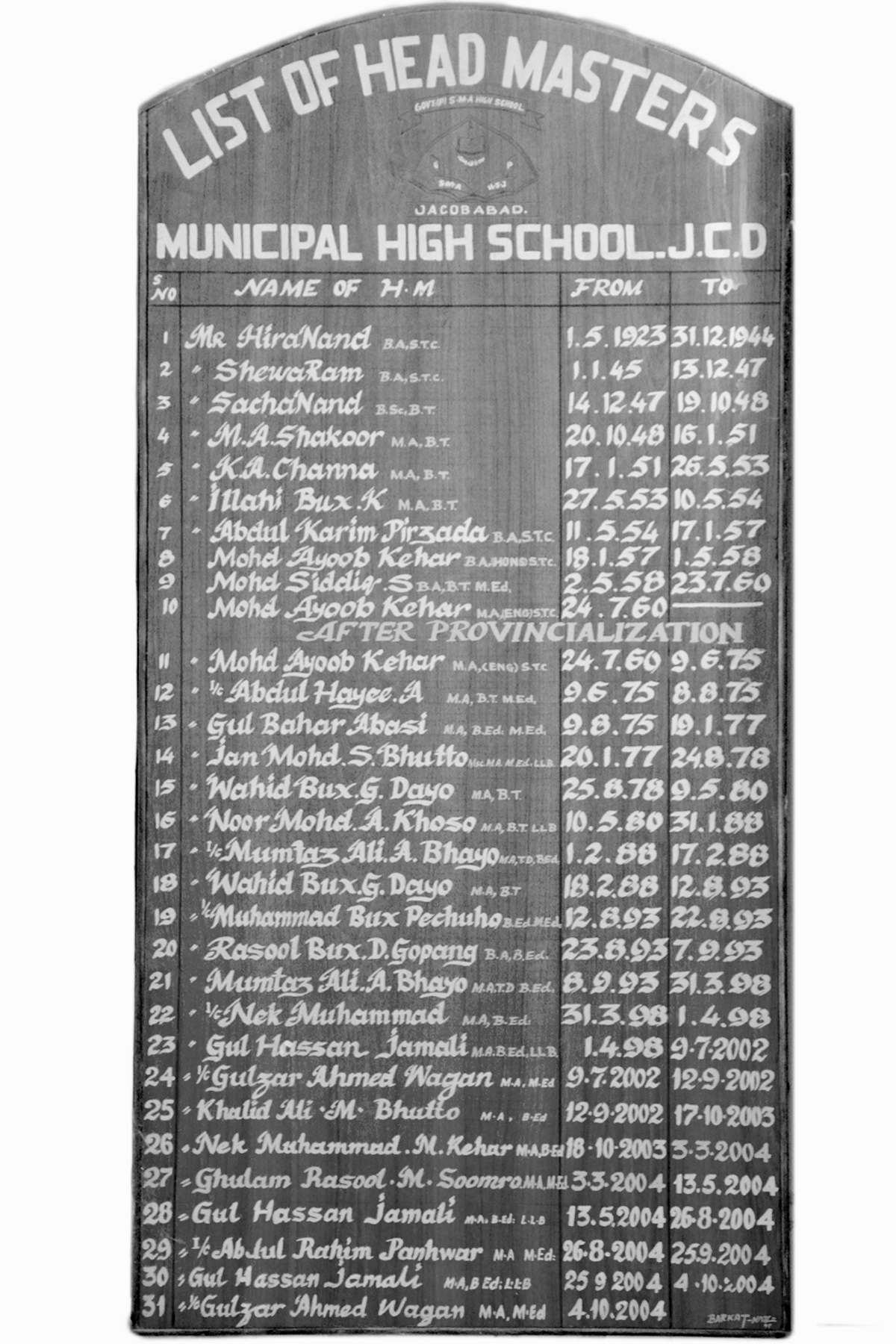

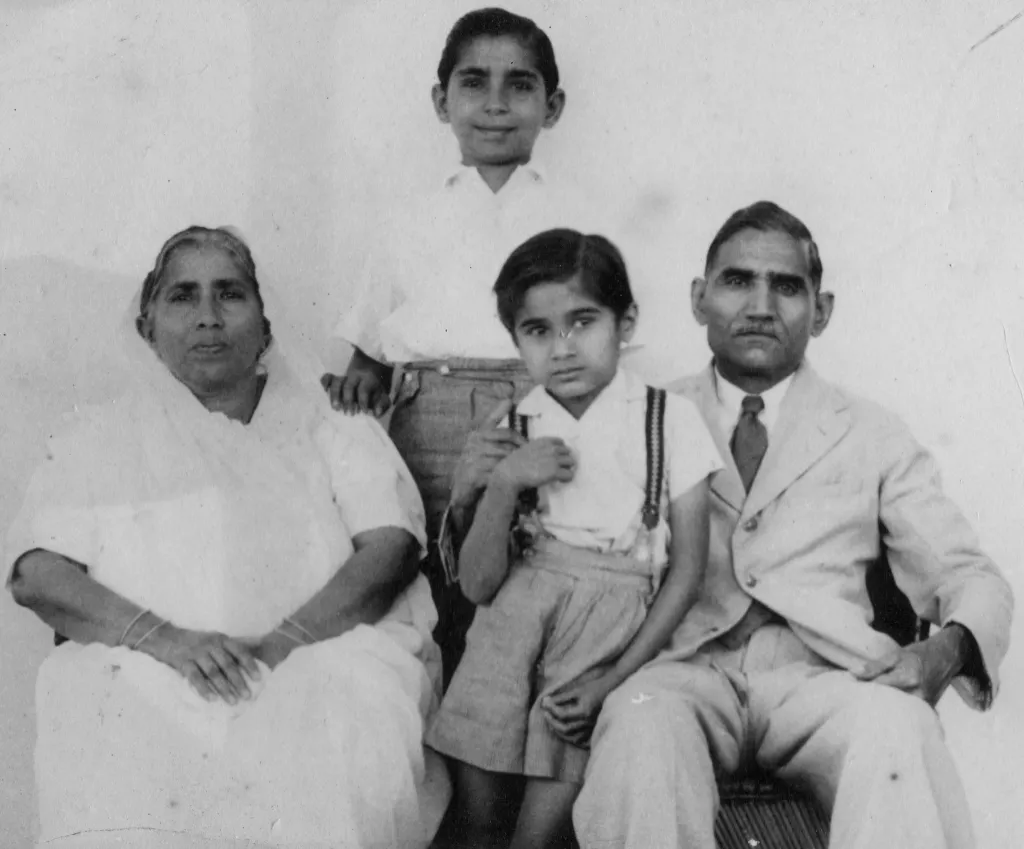

Kanu Wadhwani was born in Jacobabad, Sindh, on 19 April 1934 where his father Hiranand was headmaster of the Municipal High School.

The board displaying names of the school’s headmasters is intact even today. This photograph is courtesy the anthropologist Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro who arranged for it to be taken to accompany this text in October 2019.

The board displaying names of the school’s headmasters is intact even today. This photograph is courtesy the anthropologist Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro who arranged for it to be taken to accompany this text in October 2019.

As the headmaster of a school with eight hundred students, Hiranand was an important person. When the Governor of Sindh, Hugh Dow, visited Jacobabad on a tour of inspection, Hiranand would be called for meetings to report on progress and to submit his requirements.

Childhood in Jacobabad

Kanu would remember his hometown fondly as long as he lived, especially his home, one in a row of houses allotted to government officials, with three rooms built of brick, and an asbestos roof. The asbestos insulated the house in the cold Jacobabad winter. However, Jacobabad was the hottest city in the world, so hot that in summer, tar on the road would melt and the asbestos made it even hotter! A siesta was necessary, and a municipal staff worker, Khalifa, came to the house to work the fan, pulling a rope that moved a cloth banner from one end of the ceiling to the other, creating breeze and cooling the room while the children slept. Hiranand was particularly fond of Khalifa and would always acknowledge the connection he had with him and the other Pathan staff members, as Wadhwanis are of Nukha Pathan. The two communities differed in culture, but they shared a cordial relationship and participated joyfully in each other’s festivals.

In the evening, the children played marbles and flew kites together. Religious festivals were occasions of celebration when people exchanged greetings and sweets. Women shared household tasks and delicacies from their kitchens. When Kanu’s mother Totibai wanted to make papad, she would prepare the dough and women from other homes would come to help rolling it out. Children would then be sent to lay the thin circles out on two cots in the veranda which were covered with clean sheets of cloth to hold the papad. Under the heat of the sun, they would dry and be ready in a few hours, to be roasted or fried and enjoyed with meals or offered to guests, something every Sindhi enjoys!

Totibai and her helpers cooked the food on sigris – small stoves. Workers brought wood kindling and live coal was used to ignite it. Dal and rice were cooked in big pots on the stove, and the family ate off plates made of aluminum. Their favorite dish was pakora and they loved it so much that the family that they ate pakoras almost every day – a tradition that would continue for decades! In addition, vegetables and fruit such as mangoes and bananas were brought to Jacobabad from nearby Shikarpur. Almonds, dates and lotus seeds were popular, too, especially in the winter months, and these came to Jacobabad and other parts of Sindh, along with fruit delicacies like peaches and apples, from Quetta.

Jacobabad, with its tropical climate, was rife with snakes and scorpions, and their bites were dangerous. When spotted, servants would be called to kill them. Dog-bites were also quite common, requiring victims to be taken to the hospital in Shikarpur. But the children loved visiting Shikarpur, where their loving relatives would take them for picnics by the Sindh Wah canal and to Lakhi Dar, a quarter known for its specialty foods. Jacobabad had sweetshops, too, but Hiranand did not allow his children to eat street food. Street stands were home to multitudes of flies, and the vendors reeked from poor hygiene.

Toti was a pious lady and took Kanu and his elder brother Moti with her on regular visits to the tikano, her place of worship, where holy songs were sung, holy verses were recited from the Guru Granth Sahib, and where the priests told the history of Guru Nanak and the ten Sikh gurus. At home, the family had a framed picture of Guru Nanak. Though they followed Sikh tenets and practiced the rites of Sikhism, they did not adopt any of the outer symbols of Sikhism as they considered themselves Hindus.

School was located half a mile from the house, and featured a large playground for playing football and volleyball. Teachers were strict, and when children were disobedient, they would be rapped on their palms with a ruler or stick, or made to stand on a bench outside the classroom. Doing this was a way of nurturing discipline, which was considered essential for a proper education.

Hiranand taught English, Persian and Urdu to the senior class. His deputy was Sewaram, and the history teacher was Sambu, a pious man so engrossed in his prayers that he would be chanting god’s name constantly, even during class. He prayed with such fervor that tears flowed from his eyes. This amused the children, but they did not consider it strange since religion and a connection to the divine was essential to the environment in which they lived. To feed and clothe the religious “seekers,” who spent their lives wandering and living on alms in their quest for enlightenment, was considered a great blessing. When these seekers, or “saints,” died, their burial sites would become dargahs, places for worship where people made wishes and annual festivals to commemorate the particular saint’s birth or death anniversary took place. The countryside was dotted with these burial sites.

Karachi and the freedom movement

In 1942 when Hiranand turned sixty, he retired as headmaster and moved with his family to Karachi. Hiranand knew Karachi well since he had lived there as a student. Totibai, Moti and Kanu were familiar with Karachi too as they spent their summer holidays in the home of Totibai’s brother, Totaram Hingorani.

Moti and Kanu studied at the nearby Wadhumal Bulchand High School. The teachers were mostly women and mischievous boys were punished by being made to stand on a bench. On school holidays, the family would hire a bus and ride to Clifton to picnic. In the evenings they often visited the Karachi Gurmandar, which stood at the junction of Bunder Road Extension and Clayton Road, a place where Amils gathered to worship.

An officer had pleaded with Hiranand to leave Pakistan, explaining that it was becoming more and more dangerous for Hindus.

In 1942, Mohandas Gandhi made a historic speech, exhorting the British to Quit India. He fired his listeners with fervor, and the protest spread rapidly across the country. The leaders of the movement remained separated from their families – either underground or in jail – for months and sometimes years, until the end of the Second World War. Hiranand did not encourage his children to participate in protests since he believed in following the law and refraining from activities that were potentially dangerous. When Gandhi visited Karachi, Moti and Kanu were discouraged from attending his rally as it was likely that police were watching and those who attended might be arrested. However, their cousin Anand, Totaram’s son, was under no such restriction.

Anand had been a prominent member of the Indian National Congress for a long time. Its activists worked in hiding, printing bulletins that contained inflammatory articles to rouse the passion for freedom in their readers. These were considered treasonous and punishable by law. Every few days, wearing a suit and felt hat, Anand Hingorani boarded the first-class compartment of a train, an area generally restricted to the British and highest Indian elite. He behaved like an English gentleman, so no suspicion fell on him. He returned next day, leaving stacks of the bulletins with trusted members of the movement at each station so that they could be circulated in the towns of Sindh.

Independence – and uncertainty

On Pakistan’s Independence Day, August 14, 1947, Hiranand, Totibai, Moti and Kanu went to visit Tekchand and his family. Kanu remembers standing on the terrace and watching the celebratory cavalcade, with Jinnah sitting in a big car.

The three-mile state drive by the Viceroy and the Quaid-i-Azam – Great Leader – of Pakistan through the main parts of the city marked the end of the morning celebrations. The route was lined with British and Indian military units, the Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF), the Royal Air Force, and the Royal Indian Navy. A flight of RIAF planes flew over the procession and dipped in salute as it passed. Hundreds of people stood, watching and cheering, at every vantage point. League flags dominated the decorations on buildings, but the new Pakistan flag was prominent.

The Citizens’ Celebrations Committee erected sixteen gates on the route. Each was named after a prominent citizen of the new state of Pakistan. One of them was named after Dr. Hemandas Wadhwani, Kanu’s uncle!

Though Partition had been announced, the family had no intention of leaving their homeland. However, the situation became increasingly tense as migrants from across the new border came to Karachi, having faced violence and trauma in their homes. And, on September 10, 1947, a catastrophic event took place. A bomb exploded in a house in the nearby Shikarpur Colony. A neighbor called the police for protection from alleged attacking Muslims, but when the police arrived, they found that the bomb was detonated by mistake, not by Muslims, but by members of the RSS who had been experimenting with explosives. All RSS members present were arrested, search warrants were issued, and security forces were deployed to stamp out the revolutionary activity.

Moti and Kanu both attended RSS meetings, which served as social events where they could share inspiring stories of historical Hindu warrior kings like Maharana Pratap Singh and Shivaji. They were also trained in self-defense in case of attack by Muslim mobs. It was a warm and community-based gathering, and the children who experienced RSS in Sindh look back on it as a pleasant experience with no sinister overtones. It was indeed marked by periodic street violence, but this was not uncommon for the times.

Hiranand’s home is searched

The day after the bomb blast, a search party knocked on the door of Kaka Hiranand’s home. The women in the house ran and hid in a roomy wardrobe. Trembling in fear, knowing that all wardrobes in the house would surely be opened during the search, they chanted prayers for mercy, and for the courage to face whatever transpired with dignity.

Muslims were pouring into Karachi from Bihar and other parts of India. They needed homes, and had begun taking them from Hindus by force

Kaka Hiranand walked calmly to the door and opened it, and the police inspector in charge of the search entered the house. Members of the family stood behind doors, anxiously straining their ears to hear what was being said. Somehow, Kanu freed himself from a restraining hand and put his head around the door to see for himself what was going to happen to his father. He has never forgotten how his terror turned to amazement when the inspector bowed before Kaka and assured him that he would not search the house. Hiranand had been his school headmaster in his hometown of Jacobabad – how could he ever violate his home by ransacking it?

However, the officer pleaded with Hiranand to leave Pakistan, explaining that it was becoming more and more dangerous for Hindus. Muslims were pouring into Karachi from Bihar and other parts of India. They needed homes, and had begun taking them from Hindus by force. The problem was escalating rapidly, and it already appeared to be beyond the forces of the law to keep them safe.

Goodbye to Sindh

Kaka had been receiving his schoolmaster’s pension and expected to continue doing so, given his years of dedicated service. He never thought of leaving Sindh – why would anyone leave their home? But now it was clear that there was no choice. Dr. Hemandas helped the family secure passage on one of the ships evacuating non-Muslims from Karachi to Bombay. Kanu remembers his father weeping at the port, others consoling him, saying there was nothing anyone could do. To stay in Karachi would put their lives at risk. By leaving everything and moving, at least their lives would be safe. They would try their best and see what fate held in store.

Kanu has vivid memories of his childhood in Sindh. One of the most striking is of the love and cordiality between the Muslims and Hindus, in particular within his own family. He repeatedly reiterated, “The staff were mostly Muslim but they were very good people, they were very honest.”

In Udaipur, Hiranand – an intellectual, proficient in Persian, English and Urdu – was unable to find a job because he did not know Hindi. With their neighbors, on the streets, at the shops, while travelling by train – the family was immersed in the knowledge that they were unwelcome; they were seen as aliens. It was an uncomfortable feeling, but they kept it to themselves and made efforts to regain stability without reacting to any provocation.

Kanu remembers his father weeping at the port, others consoling him, saying there was nothing anyone could do

Unlike most of the Sindhis who were ejected from their homeland, Hiranand did not lose everything. He had invested his retirement savings in a house in Clifton, an elite neighborhood of Karachi. Less than five years later, in the turmoil of Partition, when property prices plummeted as fleeing Hindus tried to sell whatever they could and escape, he was fortunate to receive more than double the amount from his tenant, the Makrani family. This would form a good base for the uncertain future ahead of them.

In September 1948, Hiranand and Toti moved into a home in Sindhi Colony near Bengal Chemicals in Worli, Bombay. It was a step down from the home they had lived in in Karachi, but Bombay, similar in many ways to Karachi, seemed like the right place to settle.

In 1952, Kanu received an Inter-Science degree from Jai Hind College in Bombay and moved to Delhi as a student at Delhi Polytechnic for a degree in textile engineering. After he completed the course, he joined Shrinivas Cotton Mills in Bombay in 1959, where he excelled.

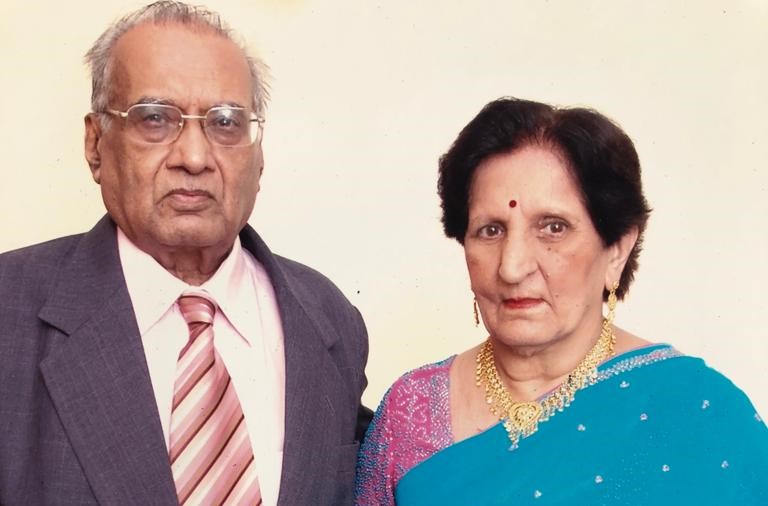

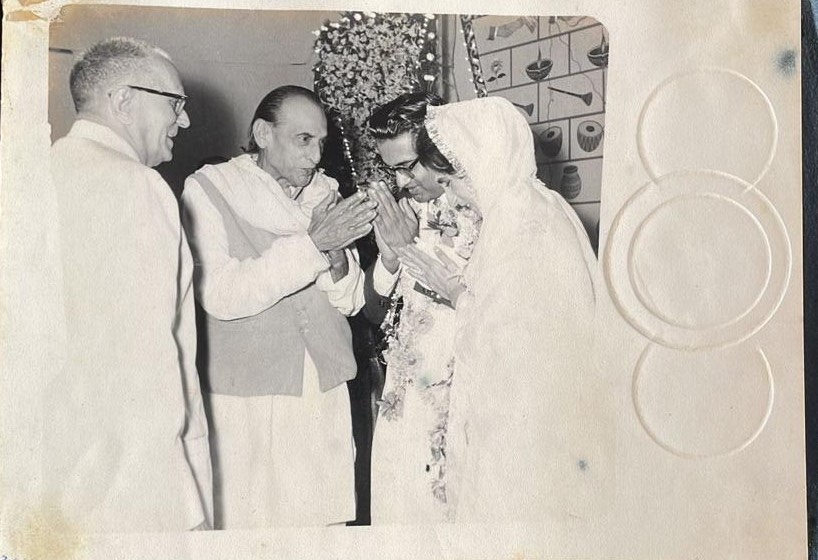

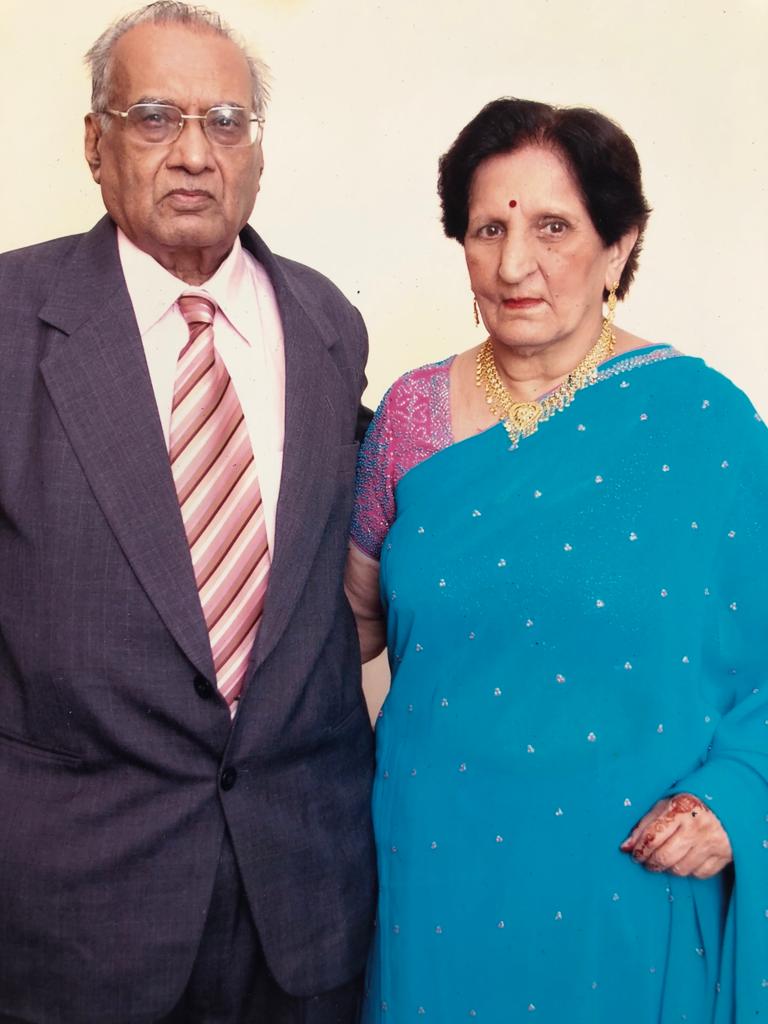

On December 31, 1961, Kanu married Roma, the daughter of Nirmaldas Gurbaxani, a well-known educationist in Sindh. He and Kanu’s father, Hiranand, had known each other for more than thirty years.

Dada Nirmaldas

Like Hiranand, Nirmaldas was a school headmaster. He led schools in Rawalpindi and Quetta, and was the Principal of Ramjas College in Delhi, then of National College in Hyderabad. It was by the efforts of people like Hiranand and Nirmaldas that the level of education in Sindh, and the awareness of the benefits of education, were far higher than in most other parts of India.

Nirmaldas was well known for his contribution to the cause of women’s education, campaigning from door to door with his colleagues, to convince parents to send their girls to school, and arranging for them to travel in covered horse carriages for privacy. In 1897, he established Nava Vidyalaya and its counterpart for girls, Nava Kanya Vidyalaya, on the principles of the reformist Brahmo Samaj movement. When his wife Kamla died in 1942, the Nava Kanya Vidyalaya was renamed Kamla Girls’ School in her memory.

After Partition, it took a tremendous effort by Nirmaldas Gurbaxani and his close family and friends to re-establish Kamla High School in Bombay. The students and teachers of the school in Hyderabad, many whose families had settled in Bombay, joined.

Life in Bombay

In January 1962, Kanu and Roma moved into their new home in Venus Apartments along with his parents.

In the 1980s, the Bombay textile mills went through a phase of militant trade unionism which eventually led to the collapse of the industry despite various efforts by the government. Sixty-four composite mills in Bombay known for spinning, weaving, and printing were affected by the strike. Shrinivas Cotton Mills had more than eight thousand employees, and when it closed, they were all left jobless. Kanu, with the advantage of his technical skills and management experience, got a job with India United Mill, later transferring to Madhusudan Mills. These were two of the twenty-five mills nationalized and resurrected under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government. After retiring when he was sixty years old, Kanu joined Prakash Cotton Mills and worked there till he was sixty-five, quitting for good when he was diagnosed with cotton fibre in his lungs and at high risk of tuberculosis.

In the 1980s, the Bombay textile mills went through a phase of militant trade unionism which eventually led to the collapse of the industry despite various efforts by the government. Sixty-four composite mills in Bombay known for spinning, weaving, and printing were affected by the strike. Shrinivas Cotton Mills had more than eight thousand employees, and when it closed, they were all left jobless. Kanu, with the advantage of his technical skills and management experience, got a job with India United Mill, later transferring to Madhusudan Mills. These were two of the twenty-five mills nationalized and resurrected under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government. After retiring when he was sixty years old, Kanu joined Prakash Cotton Mills and worked there till he was sixty-five, quitting for good when he was diagnosed with cotton fibre in his lungs and at high risk of tuberculosis.

Roma and Kanu had two children: Vijay and Mahesh. Mahesh lives in London and Vijay in Lagos.

Sadly, Roma passed away in April 2017, succumbing to non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Kanu joined her 5 years later, on May 15, 2022.

___________________

About the Author

Saaz Aggarwal is a renowned author, biographer and historian, based in Pune, Maharashtra, India. She has a Master’s degree in Mathematics, but over the years established herself as a writer and artist. Her body of work includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns, as well as themed painting collections and mixed-media installations. Her books on Sindh are in libraries of the best universities around the world.

Saaz Aggarwal is a renowned author, biographer and historian, based in Pune, Maharashtra, India. She has a Master’s degree in Mathematics, but over the years established herself as a writer and artist. Her body of work includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns, as well as themed painting collections and mixed-media installations. Her books on Sindh are in libraries of the best universities around the world.

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwal/ Sindh Stories (Posted on March 18, 2023)