[From imperial ‘unhappy valley’, to decapitated province, commercial capital, and 21st century megacity, this article reflects on relations of separateness and connectivity between Sindh and its capital city Karachi. These culminated in Pakistan’s post-Independence years, in official and political language, governances of national, provincial and city division, and political rhetoric and violence. The article asks what else might be uncovered about their relationship other than customary alignments and partitions between an alien urban behemoth and a provincial periphery. It develops a topographical view to refer to the physical arrangement of environments but also people’s profane, spiritual and political connections and losses involving place and dwelling]

By Nichola Khan

I offer a concept of ‘Sindh in Karachi’ as topography of urban deserts, rivers, hills, and terrain; a toponymy of dwellings, communities, localities, shrines, homes, and historical traces dissolved and refracted within the present. This is a mnemonic space for the urbanized spirits of saints and repeated colonization to emerge, with all colonization’s dissimulations and deceits of friendship and betrayal. It draws us to the emotional dimensions of topography, or topographica, and to how a place makes itself felt. It is not about reprising the colonial ethnographer’s story for the present, the national one, or one of any ethnic community. A topographical reading, I argue, can disrupt some real and imagined boundaries of history that separate Karachi and Sindh. It provokes questions about whether such a reading might become the object of other knowledges and constructions, planned and unplanned and, like the city, an alternative, fully contemporary force. Might it introduce something else within the border between two things, that is, ‘Sindh’, and ‘Karachi’? Political geographers of South Asia have deployed topographical notions to highlight the failure of national projects that determine territory and borders as symbols of postcolonial national unity. Akhter (2015) examines the case of water, specifically the river Indus, as a simultaneously unifying (national) and fragmenting (regionalist) force in Pakistan. At the Bangladesh–India border, Cons (2017: 3) employs the metaphor of ‘seepage’ to invoke, not imaginations of catastrophic inundation (of migrants or climate refugees), but quotidian movements across bordered spaces that signal changes at ‘inexorably different scales and temporalities’ between land, water, and spaces between. Capturing the temporalities of such movements, Hurd et al.’s (2017) metaphor of a tidemark describes ‘layers of embodied memories of movement and emotion’ (34). Tidemarks, intrinsic to ‘border temporalities’, are non-linear, concurrent, parallel, and synchronic; the past, lived present, and future coexist as people shape borders across which they move or are stopped. Correspondingly: might we, through border seepages, leakages, and tidemarks, become sensitized to the spatial and temporal rhythms of urban lives, and their lapping and overlapping histories moving between Karachi and Sindh?

This interpretive movement or exploration also describes a ‘Timely’ departure, but not in terms of the linear civilizational progress the British claimed of their arrival in Karachi (Burton, 1851). Rather, letting knowledge wander across the boundaries of existing orthodoxies can introduce unexpected incursions of critical disruption to the historical archive, and transform a view on the present. It thus evokes the silenced schisms of violence, severance and war, and the figure of the exile as constitutive of loss – that is, Sindh’s loss of Karachi, and the loss of homeland for migrants (including Sindhis) (re)settling on an alien landscape. Therein, it reveals ways the body of an exiled and migrant metropolis becomes sundered, split, and transformed into a theatre of repeated violence wherein the conflicts and physical and ontological displacements of strange encounters and cleavages from multiple pasts are dissipate through the city landscape. It also reveals ways such relations are cohesive and fecund with possibility.

This interpretive movement or exploration also describes a ‘Timely’ departure, but not in terms of the linear civilizational progress the British claimed of their arrival in Karachi (Burton, 1851). Rather, letting knowledge wander across the boundaries of existing orthodoxies can introduce unexpected incursions of critical disruption to the historical archive, and transform a view on the present. It thus evokes the silenced schisms of violence, severance and war, and the figure of the exile as constitutive of loss – that is, Sindh’s loss of Karachi, and the loss of homeland for migrants (including Sindhis) (re)settling on an alien landscape. Therein, it reveals ways the body of an exiled and migrant metropolis becomes sundered, split, and transformed into a theatre of repeated violence wherein the conflicts and physical and ontological displacements of strange encounters and cleavages from multiple pasts are dissipate through the city landscape. It also reveals ways such relations are cohesive and fecund with possibility.

Regarding ‘why partitions fail’ in South Asia, Jones (2014) emphasizes colonial hubris, ignorance, and disconnect between realities and views based on categorical data such as religion: It is ‘not that they drew the line in the wrong place; the problem is drawing lines in the first place’ (298). This bears on the epistemological value in a certain roving off familiar maps and borders and debates about geneaological versus motile forms of knowledge (Bergson, 2002; Holbraad, 2012; Ingold, 2011). It involves challenging false equivalences drawn between the map and the moving border, the fixed representation versus the fluvial flow of life, the assumed isomorphic relation between words and life, and taking a creative, contingent, and more kinetic approach to moving, living time. This can reveal ways that ‘Sindh in Karachi’ creates new pathways as it wanders through time and space, rather than following pre-defined space, and forms what De Certeau describes as a ‘migrational or metaphorical city’ (1984).

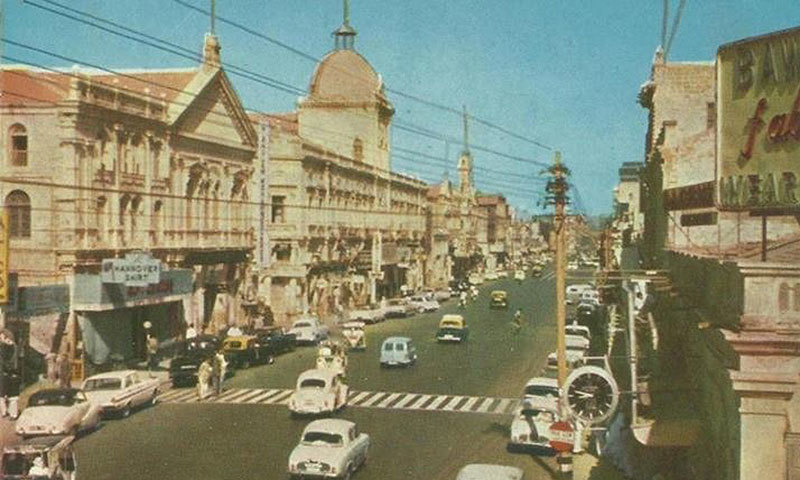

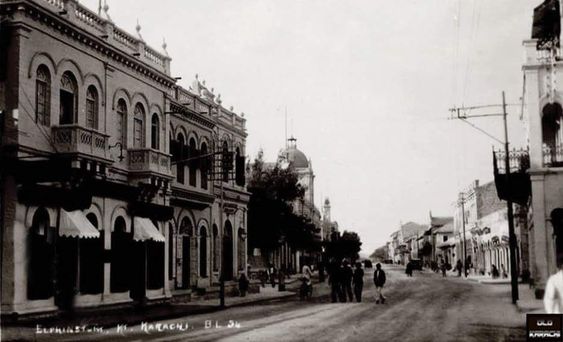

Within this framework of cartographic deviation or detour, Karachi and its incursions into Sindh also stand for another kind of topography: a palimpsest of localities and neighborhoods that in their successive multiple re-inscriptions, reclassifications, constructions, demolitions, ruins, repairs, ghostly outlines, and renovations undo and remake historical time. Sites of destruction underscore the losses of social value invested in them, and the existential losses of people whose land is trampled, pleas dismissed, and voices unheard (Jackson, 2013). Arguably, the city’s concrete layout exists only in historical time, on the map or city plan before displacements and obliterations undid memories of what it might have been (Pandolfo, 2018). Pandolfo (2018) explores the idea of the city as uncovered memory. She discusses Freud’s likening of the city to a layered grid of psychic space in relation to the notion of dwelling (material and psychic) as punctuated by knots of significance, memory-work, and forgetting. She links Freud’s metaphor of the psyche as city to his mystical notion of an ‘oceanic feeling’ to refer to a merging into the unbounded, and a sensation of eternity. This is echoed topographically here in people’s habituation to ocean, rivers, marshland and waterways, a kind of primal attachment and feeling of enclosure and envelopment. It intimates ways watery landscapes nourished by the weather evince womblike or deeper psychological structures like secure attachments.

Within this framework of cartographic deviation or detour, Karachi and its incursions into Sindh also stand for another kind of topography: a palimpsest of localities and neighborhoods that in their successive multiple re-inscriptions, reclassifications, constructions, demolitions, ruins, repairs, ghostly outlines, and renovations undo and remake historical time. Sites of destruction underscore the losses of social value invested in them, and the existential losses of people whose land is trampled, pleas dismissed, and voices unheard (Jackson, 2013). Arguably, the city’s concrete layout exists only in historical time, on the map or city plan before displacements and obliterations undid memories of what it might have been (Pandolfo, 2018). Pandolfo (2018) explores the idea of the city as uncovered memory. She discusses Freud’s likening of the city to a layered grid of psychic space in relation to the notion of dwelling (material and psychic) as punctuated by knots of significance, memory-work, and forgetting. She links Freud’s metaphor of the psyche as city to his mystical notion of an ‘oceanic feeling’ to refer to a merging into the unbounded, and a sensation of eternity. This is echoed topographically here in people’s habituation to ocean, rivers, marshland and waterways, a kind of primal attachment and feeling of enclosure and envelopment. It intimates ways watery landscapes nourished by the weather evince womblike or deeper psychological structures like secure attachments.

Pandolfo’s appeal to Freud reminds us that rhythms of psyche, memory, and the city are commensurable. It means we can uncover oscillations between corporeal mortality and eternal spirituality in the living memory of Shah Latif. These cadences are also present in traces of lives and communities before and after the devastations of death, exile, displacement, and Sindh’s crises of government, global capitalism, expulsion, and ethnic majoritarianism. This perspective can illuminate new interactions, problematize dominant cartographies that privilege Western or other hegemonic ways of knowing, and highlight ways that understandings of movements of assimilation and enculturation demand a certain linearity that people in Sindh might incorporate and also refuse. It can keep in view ways that knowledge emerges in movement as we go along and history and the city, are produced ‘in the track of things’ (Benjamin, 1999: 212).

A topographical reading emphasizes the continual syncretic fluidities and mobilities of relations and multiple place-making activities between people and environments. It bears on new political-economies of imperialism that connect human and non-human relations globally and locally. This does not denote the imperial transports of humans, plants, and other species for colonization/conservation schemes, but the ecology of planetary and post-colonial urbanization dynamics that distend mega-cities like Karachi (Sidaway et al., 2014). Brenner and Schmid’s (2015) planetary urbanization thesis is undoubtedly germane, with its imagery of new megacities and megalopolises, the transcontinental expansion of infrastructural networks, and the seizure of traditional hinterlands for large-scale energy and development projects. Likewise is Ruddick et al.’s (2017) critique of these authors’ neglect of local crisis, and the occlusion of a social ontology of the urban and its political capacities in favor of the spatial. Attending to ontologies of crisis and resistance in Pakistan inevitably evokes the specter of violence. Namely, several decades of brutal conflict in Karachi,1 ongoing insurgencies in Balochistan and Kashmir, East Pakistan’s secession, three India-Pakistan wars, and India’s and Pakistan’s development as hostile nuclear powers. It also augurs the tainted birth of the nation: the foundational violence which was nurtured by Pakistan’s political powers to legitimate the very form of democracy, or military rule, by producing a sense of continuity with the violence of independence and colonial rule (Khan, 2017). Further, it points to the continuing analytic value of post-colonialism in examining genealogies of unequal urbanisms, sites, landscapes, and in placing megacities such as Karachi on a more level analytic and comparative plain (Myers, 2014).

A topographical reading emphasizes the continual syncretic fluidities and mobilities of relations and multiple place-making activities between people and environments. It bears on new political-economies of imperialism that connect human and non-human relations globally and locally. This does not denote the imperial transports of humans, plants, and other species for colonization/conservation schemes, but the ecology of planetary and post-colonial urbanization dynamics that distend mega-cities like Karachi (Sidaway et al., 2014). Brenner and Schmid’s (2015) planetary urbanization thesis is undoubtedly germane, with its imagery of new megacities and megalopolises, the transcontinental expansion of infrastructural networks, and the seizure of traditional hinterlands for large-scale energy and development projects. Likewise is Ruddick et al.’s (2017) critique of these authors’ neglect of local crisis, and the occlusion of a social ontology of the urban and its political capacities in favor of the spatial. Attending to ontologies of crisis and resistance in Pakistan inevitably evokes the specter of violence. Namely, several decades of brutal conflict in Karachi,1 ongoing insurgencies in Balochistan and Kashmir, East Pakistan’s secession, three India-Pakistan wars, and India’s and Pakistan’s development as hostile nuclear powers. It also augurs the tainted birth of the nation: the foundational violence which was nurtured by Pakistan’s political powers to legitimate the very form of democracy, or military rule, by producing a sense of continuity with the violence of independence and colonial rule (Khan, 2017). Further, it points to the continuing analytic value of post-colonialism in examining genealogies of unequal urbanisms, sites, landscapes, and in placing megacities such as Karachi on a more level analytic and comparative plain (Myers, 2014).

Methodologically, in this article ‘Sindh’ refers to all provincial districts except Karachi, and Karachi to a separate administrative and political unit. I draw on 20 years of personal and academic connection with Karachi, during which I have analyzed aspects of Karachi life as an anthropological field-site, and site of cultural, political, and phenomenological inquiry. This conceptual paper engages a critical re-reading of the historical archive that tends, not exclusively, to read Karachi’s violent fragmentation predominantly through the lenses of ethnicity, class, and language. These presumed ‘truths’ in turn are reflected in political, media and nationalist discourse. Hence, I draw on a range of these sources. (Continues)

__________________

About the Author

Nichola Khan is a Reader in Anthropology and Psychology, and Director of the Centre for Research in Spatial, Environmental and Cultural Politics at the University of Brighton. She is author of the following books: Mohajir Militancy in Pakistan (2010, Routledge), Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi (ed., 2017 Hurst & Co.,) Mental Disorder: Anthropological Insights (2017, University of Toronto Press) and Arc of the Journeyman: Afghan Migrants in England (in press, University of Minnesota Press). She is currently developing a literary anthropological project on war and migration in twentieth-century Chinese South-East Asia.

Click here for Part-I