Sindhī community in India builds and strengthens its identity by using both traditional and modern means of transmission. The process of reinterpretation of tradition is demonstrated by the Ūmar–Mārvī story.

Aleksandra Turek

University of Warsaw, Poland

[The aim of this paper is to show how the Sindhī community in India (Rājasthān) builds and strengthens its identity by using both traditional and modern means of transmission. The process of reinterpretation of tradition will be demonstrated by discussing the Ūmar–Mārvī story, which belongs to the repertoire of orally transmitted local Sindhī folk stories. The Ūmar–Mārvī story mainly emphasizes local patriotism and adherence to motherland.]

The message of the story is still valid in the 21st century. In the Surabhi, the literary magazine on Sindhī literature in the Hindī language issued periodically in Jaypur, it took the modern form of a comic book. Thus, it provides another example of a well-known fact in Indian culture, that of the old being repeated but in a new form. Despite using modern means of transmission, traditional mechanisms can still be seen. It seems that it is not enough for the Sindhī community to continue using the folk story but, moreover, it is necessary to give the story a higher rank (a recognized one) by placing it within the frames of the mainstream tradition that is the so-called Great Tradition of the Hindu culture. This aim is achieved by making the heroine Mārvī equal to Sītā, and, thus, the Sindhī story is linked with the great epic Rāmāyaṇa. As a result, the final product is an old Sindhī folk story presented in the form of a comic book, targeted for a wider audience than the Sindhī community exclusively, entitled Sītā of Sindh (Sindh kī Sītā).

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to show how the Hindu Sindhī community in India builds and strengthens its identity by using both traditional and modern means of transmission. The process of reinterpretation of tradition will be exemplified by the narrative of Ūmar–Mārvī or Ūmar–Mārūī that belongs to the repertoire of local Sindhī folk stories transmitted orally.

Sindhīs are originally inhabitants of the province of Sindh, which is now part of Pakistan. Many Sindhī Hindus migrated to India after the Partition of British India in 1947 and in the late 1960s during and after the second war between India and Pakistan (1965). The majority of them settled down in North-Western India, mainly in Gujarāt and Rājasthān, and in Mahārāṣṭra (Bombay), which are the neighboring regions of Sindh. The population of Sindhīs in India is more than 2.5 million (2 535 485) according to the 2001 census of India and the Sindhī language has the status of an official language in the Constitution of India. There are ten important institutions in India founded for propagation and support of the development of Sindhī culture, language and literature, which proves that Sindhīs form a well-defined community in India. The 10th of April is celebrated as Sindhiyat Day (The Day of Sindhiness) in order to support and maintain the distinct Sindhī identity. The need to preserve Sindhī culture is clearly declared by Rohra in his article Sindhiyat and role of Sindhology, in which we read: “It is the sacred duty of every generation to preserve and pass on to the next generation our customs and beliefs, faith and tradition, thinking and behavior which make us feel Sindhi and love Sindhi”.

This aim is achieved by means of various strategies; for example, by linking the culture of the ancient civilization of the Indus Valley directly with the Sindhī community. Sindhīs claim to be direct descendants of the inhabitants of the Indus Valley civilization and their successors, as the ruins of the ancient city of Mohenjo Daro are located in the modern Sindh region. The claim of a direct link with this civilization is also evident through the placing of photos of certain artefacts from Mohenjo Daro on the main page of the website of the Indian Institute of Sindhology (http://sindhology.org) and on the main cover of the Sindhī literary magazine Surabhi (2003). This seems to imply that, though the Sindhī identity is distinct, it is still in the process of becoming established. The same process can be noticed in Sindh on the Pakistani side as well. In regard to literature, according to Asani, Sindhī literary tradition can already be discerned as early as in the 9th century but:

Yet it can also be argued that consciousness of a distinct Sindhi literary culture is a relatively recent phenomenon—dating only to the eighteenth century—when with the collapse of the authority of the Mughals and their Persianate court culture in Sindh, there was a remarkable growth of all types of Sindhi literature. (Asani 2003: 614)

Re-telling Sindhī folk stories also serves the purpose of strengthening Sindhī identity. Sindhī literature is dominated by the works of Sufi poets that are considered to be its most valuable literary masterpieces (for more information see Schimmel 1974). There are, however, seven folk stories transmitted orally which are identified as originally Sindhī (Khemānī 2003: 39; Devāṇī 2006: 69–72; cf. Asani 2003: 635).

The Ūmar–Mārūī story, which will be discussed in this paper, is one of them. In the opinion of Schimmel (Schimmel 1974: 10), this story could have been created during the reign of the Sūmrā dynasty in Sindh, i.e. between the 11th and 14th centuries. Part of the Thar Desert, which today is located in the province of Sindh in Pakistan, was also known under the name of Ūmar Sūmrā. The capital of this region was the fort of Umarkoṭ, which was included in the nine forts surrounding Mārvāṛ (the desert region of Rājasthān today on the Indian side). In the Arabic chronicles, the Sūmrā are listed as Muslims; nevertheless, according to Hindu sources, members of the Sūmrā line belonged to the Rājpūt clan of Bhaṭṭīs. When Muslims arrived in Sindh, the Sūmrā converted to Islam (Todd 1829–1832/1997: II: 236). One of the main characters of the Ūmar–Mārvī story is Ūmar Sūmrā—a non-generalized but individual, historical figure. Most probably he is the only one historical character of the story in contrast to the other heroes. The main heroine—Mārvī or Mārūī—is a generalized figure as well. Her name derives from the place-name Mārū.

Ūmar Sūmrā ruled from 1355 till 1390 in the region of the Thar Desert, from the capital Umarkoṭ. Men from the Sūmrā dynasty were famous for a love of luxury and abduction of women. The historical sources mention Ūmar’s father, Hammīr Sūmrā, who, in 1030, kidnapped the Gujarātī princess Jāsal. The army of Gujarāt attacked Sindh for that reason and rescued the princess (Khemānī 2003: 39–41). Maybe these abductions were so frequent and characteristic of the Sūmrās that such events were reflected in localfolk stories and became the inspiration for new narratives, e.g. for the Ūmar–Mārūī story (cf. Szyszko 2012: 175).

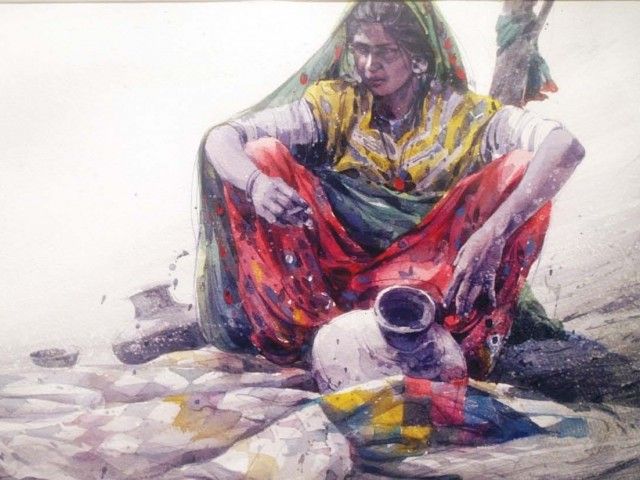

It appears that the Ūmar–Mārvī story is still well-known, as it can be found in many modern collections of Sindhī folk tales published both in India and Pakistan (cf. Khemānī 2003: 39–50; Tariq 1996: 78–83; Komal 1976: 24–28). It was also published in 2003, in the new form of a comic book, in the previously mentioned Surabhi magazine on Sindhī literature in the Hindī language, issued periodically in Jaypur (Rājasthān). The text of the comic was prepared by Vāsudev ‘Sindhu Bhāratī’ and the pictures by the artist Anant Kuśvāhā (Surabhi 2003: 73). The fact that works by Sindhī writers are published in Hindī can be understood as another ambitious attempt to reach a wider group of readers than the one limited only to the Sindhī audience. At the same time, we should also keep in mind that not all Sindhīs in India declare Sindhī to be their mother tongue. Despite being an official language, Sindhī does not have a solid utility base in India and the use of this language is restricted mainly to domestic circles. Younger generations of Sindhīs in India prefer to switch to English or Hindī (Asani 2003: 642). (Continues)

[File reloaded as it was destroyed due to database error]

_____________

Courtesy: Cracow Indological Studies