Sindhī community in India builds and strengthens its identity by using both traditional and modern means of transmission. The process of reinterpretation of tradition is demonstrated by the Ūmar–Mārvī story.

Aleksandra Turek

University of Warsaw, Poland

The outline of the Ūmar–Mārvī story

Before proceeding to its analysis, let us briefly summarize the story. The outline is based on the story published in the collection of Sindhī romantic folk stories (Khemānī 2003) and is compared with another version of the Ūmar–Mārvī story published in the comic. The main character is Mārūī (also known as Mārvī), the most beautiful woman from the Malīr village (Bhālvā in the Tharparkar district, is located about 28 miles from Umarkot). The story begins with an episode introducing the circumstances of the girl’s birth. At that time, Sindh was under the reign of Hammīr Sūmrā. One day, during the monsoon season, the king goes hunting and he gets chilled to the bone because of very cold rain and, hence, he loses consciousness. The elder’s advice heating him up with the warm body of a local young woman from the desert region. When Hammīr Sūmrā regains consciousness, he returns to Umarkoṭ with his retinue and forgets about the whole event. In the meantime, the woman who warmed the king up delivers a daughter. She gives her the name Mārūī or Mārvī. The girl grows up in the Malīr village.

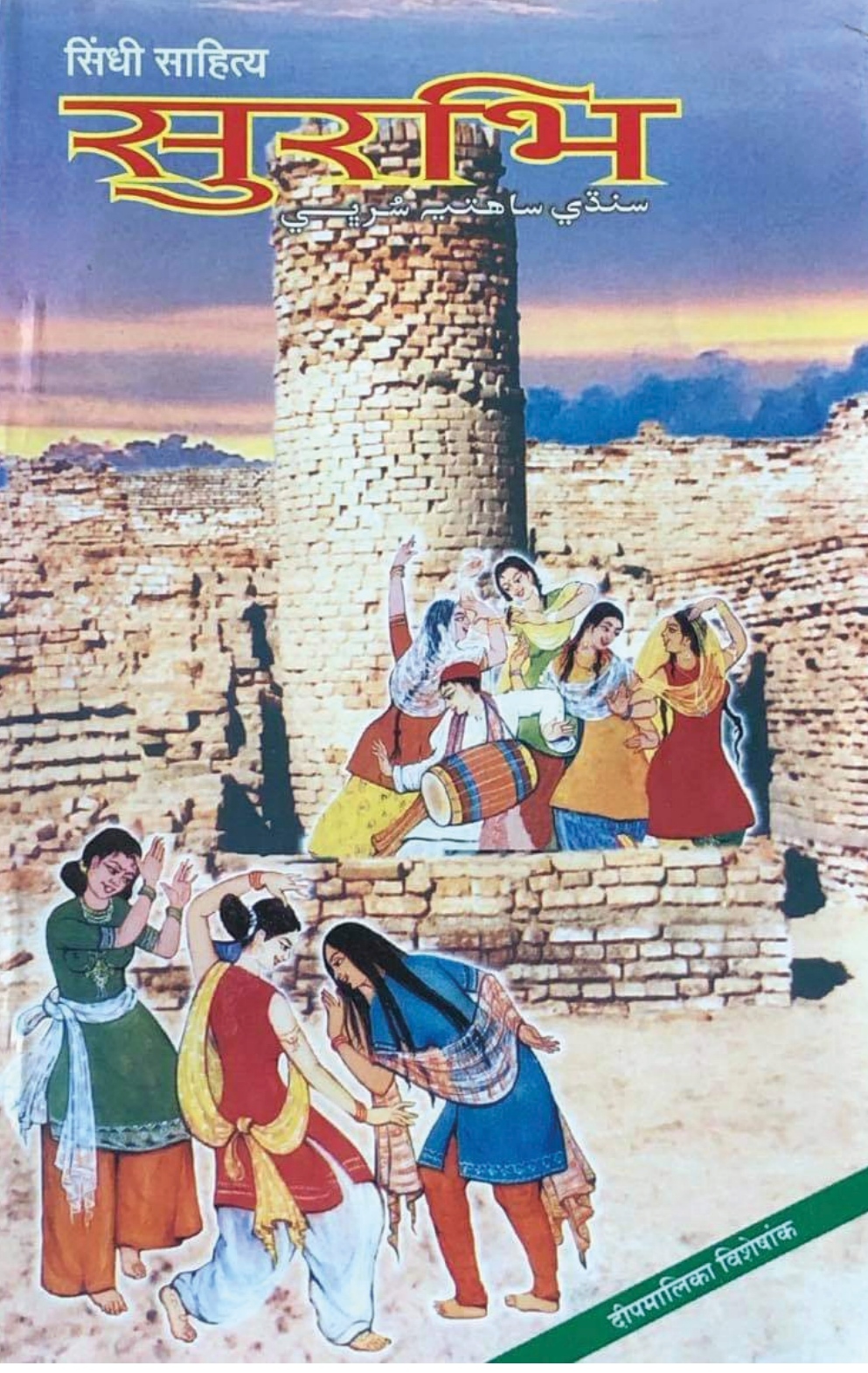

One day, a boy named Phogsen (also called Phog for short), who has worked as a servant at Mārūī’s home since childhood, falls in love with the girl. He asks Mārūī’s grandfather for her hand but he is refused because the girl is promised to Khetsen, another young man from the village (Khemānī 2003: 39). In the comic story, the plot is slightly different. Mārūī milks a buffalo cow herself and states that even her animal (named Śakuntalā) is disgusted with the servant. Mārūī, molested by Phog, is rescued by Khetsen. Phog, refused by the girl, asks the village pañcāyat (the village council) to decide who has the right to her hand and, as a result of its decision, Phog is expelled from Malīr (Surabhi 2003: 74–76).

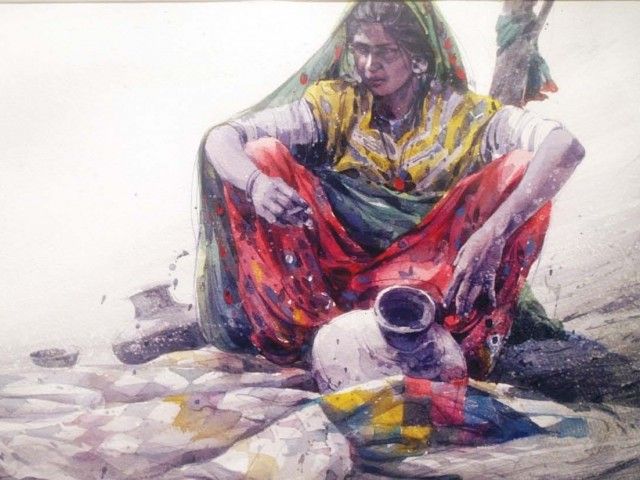

Phog decides to take revenge for the refusal of his marriage offer and travels to Umarkoṭ, where Ūmar Sūmrā, Hammīr’s son, reigns. Phog praises the unparalleled beauty of Mārūī in front of the ruler. Ūmar, encouraged by the description of her, begins to enquire about the possibility of seeing her. The boy replies that every day at dawn, she goes with her friends to the well to fetch water. Ūmar Sūmrā goes to Mārūī’s village and waits for her near the well at daybreak. When she comes, he asks her for water. After that, he uses the opportunity to drag her onto a camel and takes her away to Umarkoṭ. Mārvī explains that they are brother and sister, but Ūmar ignores it. He imprisons her in his fortress and waits until she is ready to marry him. The girl refuses food because her hands are dyed with henna, and this decoration was done at her home. She is afraid that the design on her hands, which reminds her of her home, will be removed by dipping her fingers in food. Mārūī declares that she will wash her hands only where her countrymen live. She sends back presents from Ūmar, declaring that she will not uncover her wrapper woven in Malīr village until her death. When the monsoon season comes, she sees the Mārū country in her dream (the desert region). She suffers more and more because of homesickness. Mārvī feels that she will die soon and, therefore, asks Ūmar to arrange her cremation and funeral rites in her homeland (Khemānī 2003: 41–43; cf. Szyszko 2012: 172–173). Then, in the story from the magazine Surabhi, there follows an episode which is absent from the published versions of the Ūmar–Mārūī story, created in order to make the action of the comic more dynamic.

In the kingdom of Ūmar, injustice and disorder set in because of the shameful act of the woman’s abduction by the king. Ūmar leaves his fortress and wanders in disguise in the streets of Umarkoṭ in order to learn what his subjects think of this act and he is subsequently attacked by a group of bandits and rescued by Khetsen, Mārūī’s fiancé, who had come to Umarkoṭ. When the king wants to reward him for saving his life, Khetsen asks him to send Mārūī back to her homeland. Ūmar does not agree to this. As the news of Mārūī’s abduction spread around the kingdom, Ūmar’s relative comes one day and informs him that he cannot marry Mārūī as she is his sister. Ūmar learns that he was fed on the milk of Mārūī’s mother in childhood and, therefore, the girl should be considered his sister (Surabhi 2003: 80–81).

Finally, Ūmar realizes that he did wrong. He sends her back to her home country and accepts her as his sister. On her way back from Umarkoṭ, Mārūī pays a visit to her fiancé Khetsen in his field and she asks him for water. As he has no water with him, he gives her a watermelon, but the fruit is bereft of the pulp. Mārūī understands this allusion. She spent one year in the house of another man. The fact causes her to doubt her virtue and she begins to pray.

The earth opens and absorbs her (Khemānī 2003: 39–49). Khemānī writes that there is a happy end in other variants of the story as well. When Mārvī returns home, people demand a trial of fire to prove the girl’s virtue. Mārvī comes through the trial successfully because she is innocent. She marries Khetsen afterwards and they live happily (Khemānī 2003: 49; cf. Szyszko 2012: 173).

In the comic version of the story, Mārūī returns to Malīr with splendid presents from Ūmar for all the inhabitants of the village. This also causes doubts about her virtue due to the fact that she has stayed so long in the house of a strange man. She has to prove her innocence by holding a hot iron without burning her hands and she manages to walk ten steps with a red, hot iron in her hands (Surabhi 2003: 84). She marries Khetsen afterwards and they live happily. The same variant is attested in the story published in Pakistan (Tariq 1996: 82). (Continues)

[File reloaded as it was destroyed due to database error]

___________________

Courtesy: Cracow Indological Studies