Ūmar–Mārvī story seems to be a very productive and useful tool to build and strengthen Sindhī identity in India even in the 21st century.

Aleksandra Turek

University of Warsaw, Poland

Ūmar–Mārvī: a multi-faceted story in multiple forms

Eclecticism of Sindhī culture and its literature is a well-known fact. Asani aptly notes that:

On account of its unique geographical position as a buffer zone between the Indic and the Iranian-Arab worlds, Sindh has been a place where different cultures have met and interacted with each other for many centuries. Consequently, its literary culture is characterized by convergences: between oral and written genres and forms, and between different languages, literatures, alphabets, scripts, systems of prosody, grammatical structures, and even literary symbols. (Asani 2003: 612)

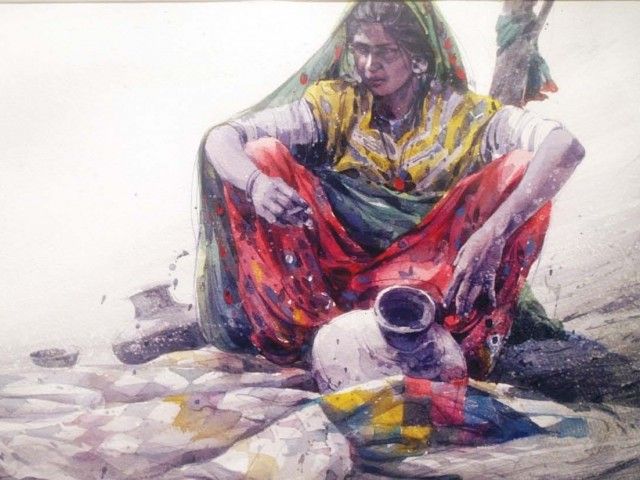

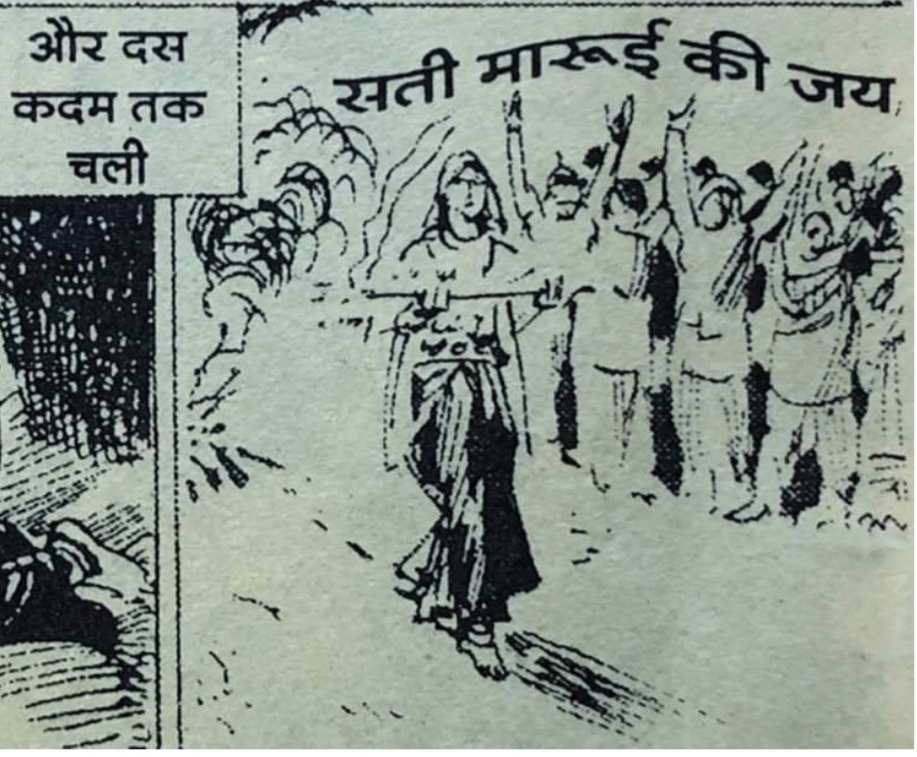

Despite the fact that the Ūmar–Mārvī is usually termed as premākhyān (a romantic, oral folk tale, very often Sufi tale), it does not represent a typical, standard love-story, as the main stress is put on local patriotism and adherence to motherland. Mārūī’s homesickness for her home village in the desert is well detailed in the story. What is significant is that the Malīr village is a real place, located in the Thar Desert. Therefore, Malīr becomes a symbol of the desert region of Sindh and Mārūī is not an ordinary village girl but the most prominent and beautiful representative of Sindh. The figure of Mārūī is celebrated during a special festival organized every year in Malīr (Surabhi 2003: 73). The importance of Malīr as an evident and well-known symbol of Sindh is corroborated by another example. A special village for Sindhī writers, artists and scholars founded by the Indian Institute of Sindhology and built on land given to the Sindhī community in Gujarāt is called Malīr. Its symbolic meaning would be unintelligible without reference to the context of the story of Ūmar–Mārvī.

The Ūmar–Mārvī also serves as a good example of how a narrative can interact with a local and mainstream culture, in various registers and in multiple forms. There are at least four forms in which the Ūmar–Mārvī story functions:

The Ūmar–Mārvī also serves as a good example of how a narrative can interact with a local and mainstream culture, in various registers and in multiple forms. There are at least four forms in which the Ūmar–Mārvī story functions:

1) In a Sufi version;

2) In a form mixed with the Rājasthānī narrative tradition of the Ḍholā-Mārū story;

3) In a Persian version;

4) Linked to the pan-Indian literature of the so-called Great Tradition.

The Sufi version

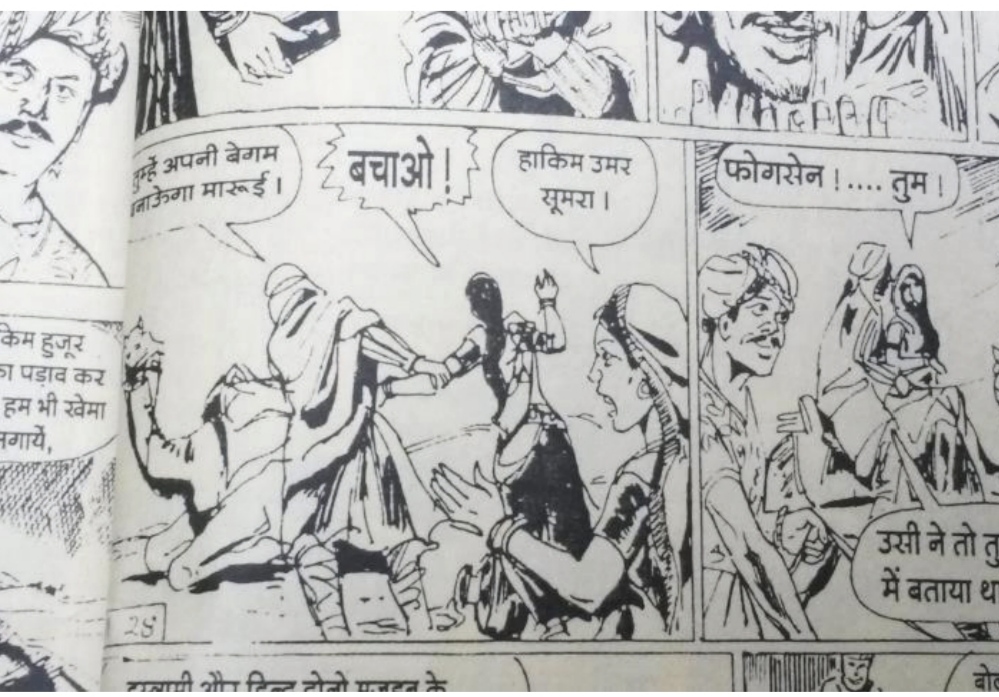

The Ūmar–Mārvī story with its message of love and strong affection for motherland was reinterpreted once again within the Sindhī culture. It was used by Śāh Abdul Latīf (1689–1752), the most prominent poet of Sindhī literature (Schimmel 1974: 14). In his most famous composition Shāh Jo Risālo (Shah’s message), he transforms the main characters of the story into mystical symbols of Sufism. Asani writes that Śāh Abdul Latīf was among these poets “who were intimately familiar with the Persianate tradition and begun to compose poetry in Sindhi. They turned to the indigenous non-literate folk/ bardic tradition for poetic forms, symbols, and metaphors that would provide their compositions with a distinctly Sindhi ethos as opposed to a Persian one” (Asani 2003: 635). Another specialist on Sindhī literature, Annemarie Schimmel, points out that in contrast to Persian and Turkish Sufi poetry, in which the love of two men symbolizes the love of a soul and God, in Sindhī poetry, a soul missing God is always portrayed as a woman who is able to endure any adversity to find the divine lover.

Thus Mārūī, who suffers from homesickness and misses the folk from her home village of Malīr, represents an innocent soul longing for the union with God. Ūmar Sūmrā represents worldly temptations that can be an obstacle on a truthful path towards God. Annemarie Schimmel notes that:

Ordinary female inhabitants of Sindh were made the main heroines by Latīf in his compositions. (…) Latīf developed the theme of Mārvī’s waiting for messages, and the imprisoned girl waits for messages from home, i.e. from God. This motif has played an important role in Sindhī literature since the times of Latīf.

The transformation of the Ūmar–Mārvī into a mystical, Sufi story reinforces the importance of this folk tale in the culture of Sindh. This also proves to be another example of the well-known fact in South Asian culture that the old is repeated in a new form.

The Rājasthānī version

The Rājasthānī version

Mārūī (known also as Mārū), as the most prominent representative of the Thar Desert country, also functions in the same role in a folk tale from Rājasthān—the Ḍholā-Mārū story. It is a story originally in Rājasthānī that was created in the desert region. In the beginning, it was most probably circulating in the form of a set of folk songs about a local woman (Mārū), an inhabitant of the Thar Desert, who was longing for her absent husband (Ḍholā) and, hence, suffering the pains of separation. The Ḍholā-Mārū as a story transmitted orally is superregional, spread through the whole region of North India, but only in Rājasthān in the 16th–19th centuries did it appear in the written form of an elaborated poem, generally known as the Ḍholā Mārū rā dūhā. The fact that the Ūmar–Mārvī was added to the more widespread narrative tradition proves its popularity and its super-regional spread; however, it then loses its typical Sindhī features.

It is worth noting that not only were the episodes of the Sindhī story added to the literary tradition of the Ḍholā-Mārū, but the Rājasthānī story also permeated to the region of Sindh. At least eight oral versions of the Ḍholā-Mārū story are found in Sindh as well and this narrative was also reinterpreted by Śāh Abdul Latīf in his famous Shāh Jo Risālo. The analysis of the interconnection of the stories of Ūmar–Mārvī and Ḍholā-Mārū has already been published. In the Rājasthānī story, the same episode with Ūmar Sūmrā wanting princess Mārū for himself also appears but only in its traditional literary form—in the medieval poem, Ḍholā Mārū rā dūhā. Szyszko has tried to demonstrate that the common name shared by the main heroines of both stories, and the fact that their names indicate their connection with the desert, as well as the common figure of their torturer (Ūmar Sūmrā) facilitate the process of mixing these narratives (Szyszko 2012: 176), but let us not forget that both stories belong to the same milieu of the Thar Desert culture. Despite being labelled as Sindhī or Rājasthānī, the cultures interacted mutually and, therefore, until the Partition in 1947, the borders were not so clearly distinct. One version of the Ḍholā-Mārū story popular in the whole region of Sindh proves this fact (Āġhā 1985: 21). This variant is de facto a mixture of both stories—Ḍholā-Mārū and Ūmar–Mārvī—and, as a result, there are many inconsistencies in the plot. In the Rājasthānī story, Ḍholā is always Mārū’s husband, but in this version, however, he travels to Umarkoṭ to meet his wife and accepts her as his sister (sic) (for a summary of this story see Szyszko 2012: 265). This also points to the fact that the Ḍholā–Mārū, which does not belong to indigenous Sindhī narratives, in less known or even totally unknown passages, is supplemented with a story better-known to the audience of Sindh—with elements of the Ūmar–Mārvī story (cf. Szyszko 2012: 176). Nevertheless, because episodes of the Sindhī story were added to Ḍholā-Mārū rā dūhā, which is acknowledged as the jewel of Rājasthānī literature, the status of the Ūmar–Mārvī story is elevated as well. (Continues)

_________________

Click here for Part- I and Part- II

Courtesy: Courtesy: Cracow Indological Studies