Climate change – largely driven by the burning of fossil fuels – has contributed to an increase in the frequency and severity of heatwaves in every world region, including South Asia.

Monitoring Desk

For weeks, blistering heat has swept across India, Pakistan and other parts of Asia – leaving millions of people struggling with severe impacts.

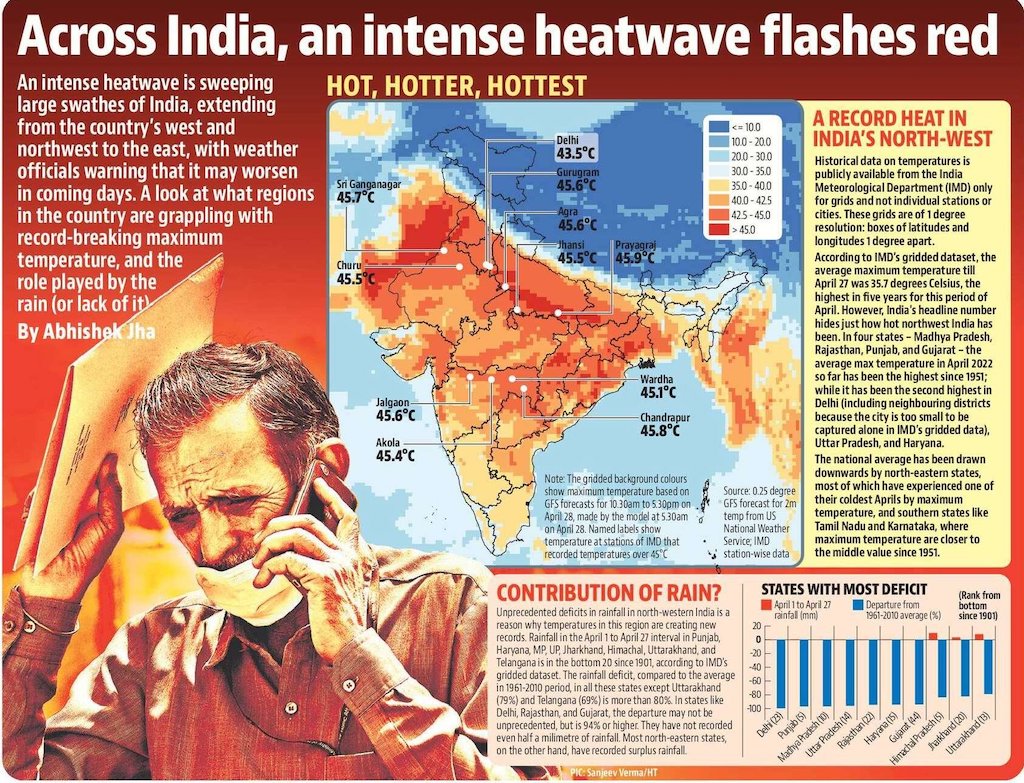

The extreme heat first began in early March, with temperatures reaching above 47C in India by the end of April and 49.5C in Pakistan in May.

Across south Asia, the sweltering temperatures have been linked to an uptick in heat-related deaths, wheat crop failures, power outages and fires – with poor and marginalized communities particularly affected.

Climate change – largely driven by the burning of fossil fuels – has contributed to an increase in the frequency and severity of heatwaves in every world region, including South Asia, according to the world’s leading climate authority.

What is happening with heatwaves in Asia?

Parts of central, south and western Asia, including India and Pakistan, first began experiencing extreme heat in March, the Washington Post reported.

India’s Meteorological Department (IMD) said March maximum temperatures were at their highest in 122 years in the country, according to the newspaper.

At the same time, it added, Pakistan “had the highest worldwide positive temperature anomaly during the month of March, meaning the margin between observed temperatures and averaged temperatures there was bigger than anywhere else across the globe”.

The arrival of heat in India in March is “unusually early”, Associated Press reported, noting that the country’s summer months are considered to be April, May and June.

Northwest India, including the capital territory Delhi, was particularly affected by the March heat, according to the Wire.

Quartz India added that 2022 is the second year in a row where March temperatures have been unseasonably high across the country, with 2021 recording the third hottest March on record.

India Today reported that the IMD considers an area to be experiencing a heatwave if maximum temperatures exceed 40C in lowland regions, or at least 30C in the highlands, for at least two consecutive days.

A heatwave is also declared if temperatures are 4.5-6.4C above average, with temperatures 6.4C above normal classified as a “severe heatwave”, according to the publication.

It noted that the threshold for heatwaves was much higher in India than the UK. (In March, the UK’s Met Office raised its threshold for heatwaves from 27C to 28C in the warmest parts of the country.)

A scientist at IMD told India Today that the thresholds differ because “different countries have different climate conditions”. He added:

“The Indian sub-continent has a tropical climate with high temperatures. Therefore, in countries like India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka heatwaves [are] declared at higher temperatures compared to that of the UK.”

The heat continued into early April, with parts of India and Pakistan experiencing 42.6C and 43C, respectively, in the first week of the month.

At the same time, other parts of Asia sweltered in unusual heat. Temperatures in Uzbekistan reached 30-33C, 8-10C above average for early April, according to the Third Pole.

Meanwhile, Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, experienced temperatures of 36.6C – 6C higher than the previous record for this date, set in 1991, the Third Pole reported.

By 8 April, seven Indian cities were experiencing temperatures above 44C, the Hindustan Times reported, with Kandla in Gujarat experiencing 45C heat.

The above-40C heat continued to engulf India throughout April, with northern and eastern states – including West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha – particularly affected, Telegraph India reported.

On the last day of April, temperatures in Jacobabad, Pakistan hit 49C – the first recording of 49C heat in the northern hemisphere this year, the Guardian reported.

And temperatures in Pakistan climbed higher still – with Nawabshah hitting 49.5C on 1 May, Axios reported.

Meanwhile, in India, temperatures in Banda, Uttar Pradesh, reached 47.2C on 29 April – a record for the month in the city, Axios said. Other such records were set on 30 April in Gurgaon, Chandigarh and Dharamshala. The month as a whole is likely to be the hottest April on record for northwestern India, it added.

On 2 May, the Hindustan Times reported that the heat is likely to subside in most parts of India this week, with the IMD predicting stormy weather in Delhi, eastern and northeastern states in the coming days.

And Reuters reported that India’s monsoon rains – which typically bring relief after the hot summer months – are expected to be “average” this year.

What are the impacts of the extreme heat?

What are the impacts of the extreme heat?

On 25 April, the IMD issued heatwave warnings over several districts of West Bengal, warning residents to avoid prolonged heat exposure.

“Recognize the signs of heat stroke, heat rash or heat cramps, such as weakness, dizziness, headache, nausea, sweating and seizures. If you feel faint or ill, see a doctor/ hospital immediately,” the bulletin said.

By the afternoon of 28 April, heat-related watches were “in effect in all but a few of India’s 28 states, encompassing hundreds of millions of people and most of the country’s major cities,” the New York Times reported.

Hospitals quickly began to fill up, as people succumbed to the heat. The Financial Times quoted Dr Madhav Thombre, a general practitioner based in Mumbai, who said:

“We are seeing many cases of heat exhaustion, dysentery, body ache – and the number of viral fever cases have increased too since the last two weeks.”

“Poorer women are particularly vulnerable to heat stress because they tend to work from home without air conditioning, while they also cook, which is hot work, and gather provisions and water from outside the house,” the Independent added.

Meanwhile, the Guardian and IFL Science reported that the heat posed a particular danger for people in India and Pakistan practicing Ramadan, who do not eat or drink during the day.

Writing in Climate Home News, Delhi resident Sapna Verma said “the heat in Delhi is unbearable”. In the article, Verma described falling ill after walking 2km in the mid-afternoon sun. She continued:

“A couple of days later, returning from the office, I took a cycle rickshaw, pulled by a man who must have been in his mid-40s. Throughout the 15-minute ride to my home, the rickshaw puller, a Muslim, kept quiet. But while waiting at a red light he said he would not be able to maintain his Ramadan fast until evening because of the heat.”

On 3 May, Reuters reported that “India’s western state of Maharashtra has registered 25 deaths from heat stroke since late March, the highest toll in the past five years”.

Similarly, on April 29, Gulf News reported that “Pakistan’s climate change ministry issued a heatwave alert in all provinces and advised people and authorities to take precautionary measures”.

Down To Earth reported on heat’s impact on mental health in the central Indian state of Jharkhand that “has recorded 11 heatwave days this year”. The story quoted Dr. Basudeb Das from the Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP) in Ranchi, who said:

“One standard deviation of temperature increase leads to a [4%] increase in interpersonal violence and 14% increase in group violence. High-risk behaviors also increase during heat waves. Evidence has shown that having a pre-existing psychiatric illness can triple the risk of death during a heatwave.”

Meanwhile, the Conversation reported on the working hours lost due to the heat. “It’s become impossible to work after 10 o’clock in the morning,” Sunil Das – a rickshaw puller in Noida on the outskirts of Delhi – told Quartz. The piece continued:

“The searing heat has forced outdoor workers like Das to change their working hours. ‘I head back home after 10 and resume in the evening when the heat has subsided a bit,’ Das said. ‘It has reduced my earnings, but what alternative do I have?’”

In the eastern state of Odisha, people set up stalls at prominent public places to offer water to passersby, Reuters reported. The Odisha state government announced the closure of Anganwadi centers, colleges and universities for five days from 27 April, according to Times Now.

Elsewhere, the Bengal government advised all state primary schools to shift school hours to the morning to avoid the heat, the Times of India reported.

As millions turned to air conditioning to keep cool, India’s electricity demand touched a record high in April, Reuters reported.

Manufacturers posted record growth sales of residential air conditioning units for April, according to Business Standard. In addition, the Economic Times of India reported that manufacturers of air conditioners and refrigerators increased their production from 60-70% capacity to full capacity. However, the Hindu added that increased demand for air conditioning units may also lead to shortages and price increases.

Meanwhile, the Financial Times reported that rising demand for air conditioning was “worsening a critical shortage of the coal that is used to generate power for New Delhi and other nearby cities”. This triggered “the worst power crisis in more than six years”, said Reuters.

The Daily Telegraph reported that authorities in Delhi warned on 28 April that the city would see power cuts across essential services over the weekend, including in hospitals and on its metro trains, due to record levels of residential power demand.

That day, Bloomberg reported that India had cancelled some passenger trains to allow the faster movement of coal to power plants. “Coal reserves at India’s power plants have declined almost 17% since the start of this month and are barely a third of the required levels,” the outlet said.

On 4 May, the Financial Times reported that India has plans to boost coal production to “record highs” in response to the power crunch. Meanwhile, Bloomberg also reported that states including Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh were forced to implement eight-hour blackouts.

The Hindustan Times added: “In Jammu and Kashmir, unscheduled and prolonged power cuts during [Ramadan] have left citizens distraught.” Meanwhile, the Economic Times of India reported power cuts of up to 12 hours in Pakistan to reduce stress on the national power system.

On 2 May, the News in Pakistan reported that residents of the Nawabshah town of Sindh were facing unannounced hours-long power outages. Due to high fuel costs, citizens were unable to use generators for domestic power production, the paper added.

“The sweltering heat and unannounced power cuts during the month of Ramadan made the almost 15-hour fasting even more challenging…The power shortfall reached 7,468MW, resulting in long hours of about 6 to 18 hours of power outages a day in several regions of rural and urban Pakistan,” according to Gulf News.

The paper added that the country’s power division has injected an additional 2,500MW of electricity into the power system in an effort to end the power cuts.

A combination of extreme temperatures and hot, dry winds across north-Indian planes also “caused scores of unusual farm fires in food-bowl states over the past two weeks, destroying swathes of harvest-ready wheat crops in at least four”, according to a separate report by the Hindustan Times.

The Financial Express said that wheat outputs will be at least 10% below initial estimates.

And the Statesman added that the Punjab government sought to relax rules on the “normal appearance of grain”, in view of the “shrivelled” grains that were being harvested.

Meanwhile, Reuters reported in early May that, due to the heat, “India’s wheat output looks likely to fall in 2022 after five consecutive years of record harvests”. The Guardian added that water shortages also affected farmers, forcing them to “use water sparingly”.

This comes at a time when India is “counting on a bumper crop to tap an export market left struggling with a gap in supply due to the Ukraine war,” the Hindustan Times said.

Similarly, Gulf News reports that “Pakistani farmers face the dual threat of enduring severe hot conditions on the job and heatwaves affecting the quality of crops”.

On 4 May, Bloomberg reported that the Indian government is now “considering limiting wheat exports” to safeguard domestic supplies.

Elsewhere, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi warned that high temperatures are also causing fires to break out more frequently in “jungles, important buildings and in hospitals”, Reuters reported.

And gases emitted by a landfill site at Bhalswa in Delhi spontaneously combusted on 26 April – emitting “a thick layer of toxic smog across the city”, according to the Daily Telegraph.

In a piece entitled, “Delhi is a blazing hot, smoke-filled hellscape”, Quartz reported that the fumes “worsened Delhi’s air quality, already among the worst in the world”.

Meanwhile, as the waters warmed, fisheries began to see smaller yields – reducing profits for Mumbai’s 40,000 fish sellers, Reuters reported.

Finally, around seven million people are currently at risk of flash flooding from the rapidly melting glaciers – and the government of Pakistan told provincial disaster management authorities to prepare urgently for the risk of flash-flooding in northern mountainous provinces, according to a separate Reuters story.

What role has climate change played in the heatwaves?

The IMD defines four climatological seasons, with the “pre-monsoon” summer season stretching from March to May and ending with the onset of the southwest monsoon in early June.

Summers in India “have always been grueling”, according to BBC News – “especially in the northern and central regions”. The outlet noted that “heatwaves are common in India”, but that “summer began early this year” with the onset of heatwaves in March.

The season’s first heatwave was declared on 11 March, according to Down to Earth, an Indian environmental publication.

Dr. Naresh Kumar, a senior scientist at the IMD, told BBC News that the current heatwave is attributable to “local atmospheric factors”, such as persistent anticyclones and weaker-than-usual “western disturbances” – storms that originate in the Mediterranean and bring rainfall to India.

Dr. Naresh Kumar, a senior scientist at the IMD, told BBC News that the current heatwave is attributable to “local atmospheric factors”, such as persistent anticyclones and weaker-than-usual “western disturbances” – storms that originate in the Mediterranean and bring rainfall to India.

The Washington Post explained that “a dome-like ‘ridge’” of high pressure in the atmosphere “eradicates cloud cover and deflects storm systems to the north…allow[ing] sunshine to pour in unobstructed, heating the antecedent dry air”. (A similar mechanism was at play during last year’s “heat dome” event that baked the Pacific north-west region of the US and Canada.)

Delhi “failed to see a single rainy day” in March, following a record-wet January and an abnormally wet February, the Hindustan Times reported. It added that only “weak and feeble” western disturbances made their way across the country’s northern plains. It added:

“Not only did these [western disturbances] fail to bring rainfall, but sufficient cloud cover, too – one that can provide a slight cooling effect.”

The New Scientist reported that this heatwave is “notable” because the world is currently in a La Niña state, which, it explained, “usually has a cooling effect globally”. It pointed out that the previous records, set in 2010, occurred during an El Niño year, when global temperatures tend to be boosted.

Axios called the heatwave a “climate change-fueled event”, noting that studies have demonstrated “clear causal links” between heatwave intensity and climate change.

(For reading complete report, click here).

__________________