Monica’s grandfather was the first in their family to go to Gibraltar. In those days, the men of their community left in shiploads and most of them were employed by Sindhis to work in their overseas shops.

Introduction

Monica Mahtani Bhojwani was born in a prisoner of war camp in France on November 22, 1940, and passed away on March 4, 2020 at the age of 79. She had an exciting story documented in her first book. Monica grew up in post-Partition Karachi. As a young bride, she moved to Gibraltar, where she and her husband Santu lived for ten years. After the subsequent twenty-five years in Las Palmas, they settled in USA to be near their children. Monica, who was never a typical Bhaiband woman, saw herself as an American Bhaiband. When she was young, she rebelled a little against forced traditions and found her own way of processing what she believed in and what she didn’t.

In this historically authentic account of some important events of her life, we get a sense of what it was like for the Bhaiband women of Sindh.

The gyaro paro stage of life

In those days, when a woman’s son got married, she sat back and let her daughter-in-law do all the work. Once a woman turned forty, it was her turn to sit on a khatta in the angan all day long and control things by giving orders. You could tell by what a woman was wearing—a gyaro paro, a long red skirt made with ajrak material and a white top—that she was in that phase of life. My grandmother, with four daughters-in-law, had been wearing the gyaro paro for a while. Like other women in that phase and station, she had a big natha, a heavy nose ring with a large ruby and a black thread that went into her hairline to hold the weight. She wore it all the time, even when she was asleep.

With four daughters-in-law, my grandmother had her favorites. Not surprisingly, the one who got the best treatment was the one who had brought a nice big dowry. She happened to be the youngest, and came from an aristocratic Bhaiband family, the Mahboobanis.

My mother would not have had much of a dowry. She came from an educated family and her father, Tekchand Gulabrai Sadhwani, was a magistrate in Hyderabad and a well-known, influential person. They were more inclined to the Amil way of progressive thinking (Amils are another Sindhi community, more inclined to education and government service, unlike us Bhaibands who are invariably in business). However, she was an excellent cook and was given charge of the kitchen. In a home with twenty-five people, a lot of kitchen supervision was needed. Her special skill was making mithais, traditional sweets, and when there was a wedding in the family she would make huge thalis (platefuls) of mithai which would be distributed. I remember seeing her in the afternoon sitting in the angan, stirring a huge pot on a stove of burning coal. It took hours of constant stirring to get the mithai ready so her hands would be sore and I would feel sorry for her, but she was totally absorbed in getting it just right and, later, experiencing the satisfaction of everyone enjoying it.

The eldest derani, the wife of the eldest brother, had the keys to the family cupboards and was in charge, directly under my grandmother. With her daughters-in-law taking care of all the household tasks, my grandmother was always looking for ways to save and invest money. She would even skimp on food to invest in something. She would tell my dad, ‘Look for property!’ When he came home in the evening she would ask him, ‘Have you earned well today? Did you make money?’ And he would reassure her, ‘Yes! I earned lots and lots today.’ Some days he would bring piles of notes and affectionately put them in her lap. That was his way of making her feel secure and well-off. Since women did not have a source of income, we always tended to have a feeling of insecurity. There was always the urge to save so that we would have enough for tomorrow, in case of a crisis.

In our days, girls were not brought up to work and earn. The main concern was to get a daughter married and out of the house to her ‘real’ home. Thoughts of her marriage would begin right from the day she was born. My mother-in-law was already engaged to be married at the age of nine. At 13, she was sent to her in-laws and soon her childbearing years began. This was common across our community. I remember Dada Mangharam, my father’s elder brother who was like the boss, the head of our family of 25: the brothers, their wives and their children. He would tell us girls, ‘Hurry up and get married! Get married and get out.’ Girls took a dowry when they got married so families needed the money to give dowry. That’s why money was so important, I suppose.

But women were never encouraged to develop any kind of identity outside the family. Bhaibands always lived in joint families. The mother-in-law kept her eye on her daughters-in-law. It was their duty to do the work of the house and to serve her. As a result, Bhaiband women had to lead very disciplined lives. In one of the places I lived as an adult, I had a neighbor of my mother’s generation who would tell me about how her mother-in-law did nothing but sit there, watching her like a hawk. She and her husband did not even have privacy in the bedroom and were expected to sleep with the door open. She had children but when she tried to hug and caress them, her mother-in-law would taunt her, ‘Stop it! Is that all you are going to do all day?’ The only entertainment, the only reason for a woman to leave the house was when there was a death in the community. She would then be obliged to attend the marko, a ceremony held four days later, and to visit the gurudwara daily for twelve days. So when her mother-in-law left the house, she would fling off her dupatta and prance around for a bit! And then she would pick up her children, swing them up in the air and hug them and squeeze them as much as she wanted before her mother-in-law got back. My grandmother was not such a despot but she did control her daughters-in-law in her own way and excessive display of emotion was definitely frowned upon.

Amma refused to mourn

My grandmother was deeply attached to my father. In 1940, when the news came to Hyderabad that SS Kemmendine had sunk, families whose members had been on board went into mourning. However, Amma refused to go into mourning, to sit on the floor and moan and wail as she was expected to. She kept saying, ‘Hotu will come back. I know I will see him.’

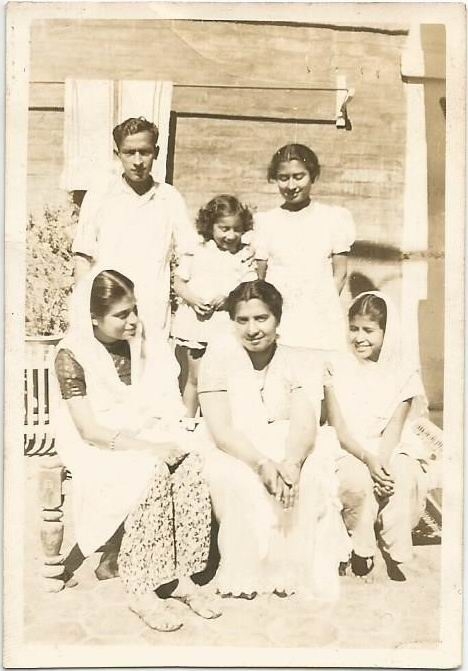

She found out about a fortune teller who lived nearby and sent her eldest daughter-in-law and her granddaughter Gopi to her. The woman told them that she could see Amma’s son. Next to him she saw a lady wearing white clothes with a baby next to her. They came back to Amma, overjoyed. They had not known that my mother was expecting. Amma clung to this piece of knowledge and it gave her strength. My father was eventually able to send a message to his elder brother who was in Gibraltar telling him that they were safe and now had a baby girl.

Sadly, the news came too late for my grandfather. Overcome by grief, he had lost his memory. When my father eventually returned home, he would sometimes say to him, ‘Do you know where Hotu is?’ And ‘Have you seen Hotu?’ There were times when his memory returned fleetingly and he would say, ‘Oh Hotu! You are back!’ but then it would go again. This must have been heart-breaking for my father, his primarily motivation to survive had been to come back home and see the joy on his parent’s faces at his return. Two years after we returned home my grandfather had a heart attack and died. I was four when we came back and do have a faint memory of sitting on his lap.

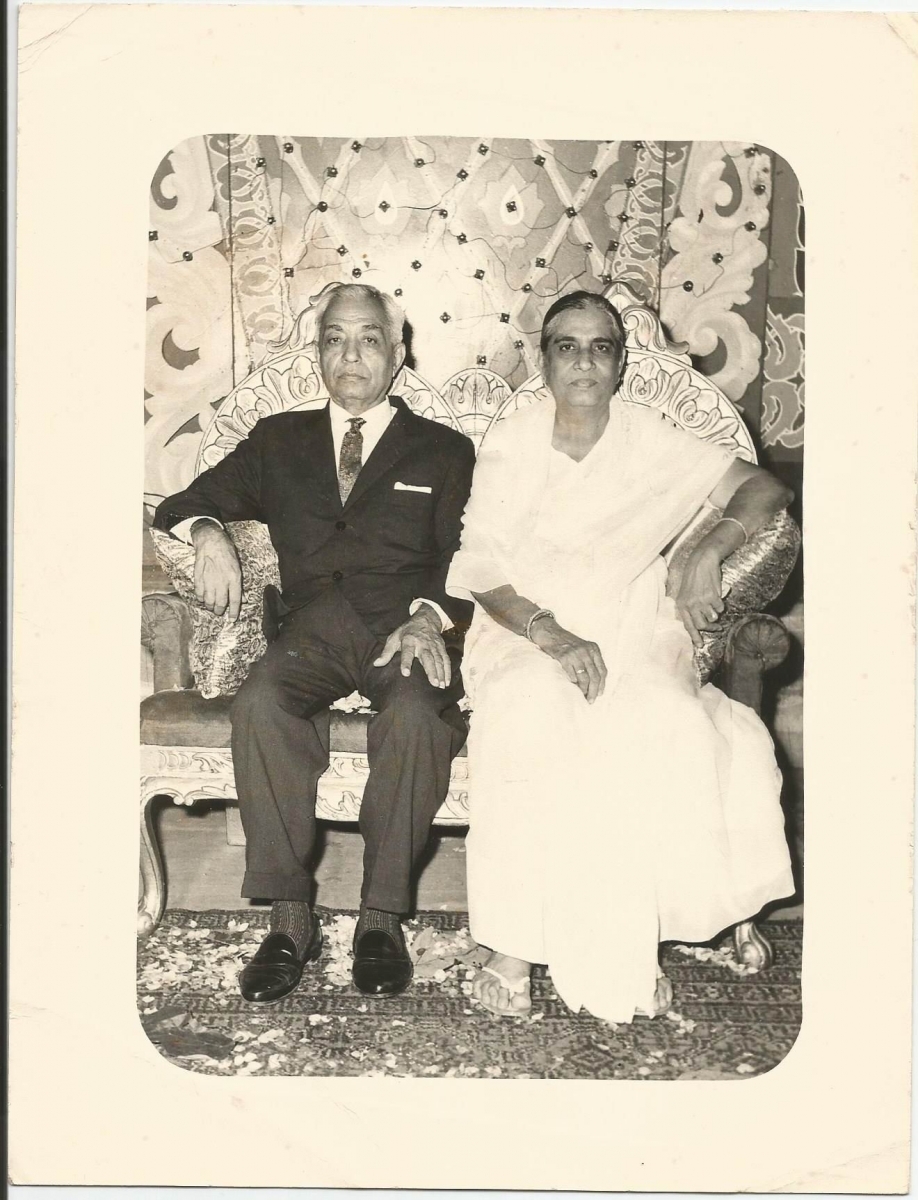

My grandmother continued to run the household, as she had always done. It could be that living on her own without a man all the years that my grandfather was away had given her strength and independence. So her status did not change after she became a widow; she continued to be the boss. It was this way with most of our Bhaiband matriarchs. Years later, my father opened a company in her name, Isar. I suppose her sisters-in-law and others of her age called her by that name. For us she was just Amma. About three years after Partition, Amma passed away.

Partition

It so happened that many men of our family were in Hyderabad at the time of Partition. During the Second World War, families had got separated. There must have been some who never came back home, and others who, like my parents, had survived all kinds of hardships and wartime escapades. They were now back in Sindh, enjoying being at home. When the rumors of Partition started, people started packing up and leaving, taking their families away from Sindh and moving to the places where they had their businesses or to a safe country. Daulatram and his family had left earlier on, to establish a business in Bombay and were not there during Partition but my father and Mangharam decided to stay on in Karachi with their families. It was their home, why should they leave?

We had malis (gardeners) and drivers and a chowkidar (security guard) at the door and they were all Muslim and we were comfortable and felt safe with them. My father had many dear Muslim friends too, and never feared them. However, there were people from our community who felt that Muslims were hot tempered, angry and vengeful. There was quite a large section that didn’t like Muslims at all. They were all right with them at a distance but didn’t like to deal with them. I remember my mother’s parents staying overnight with us. They had left their home in Hyderabad and were moving to Bombay. My grandfather, Gulabrai Sadhwani, would not even drink water in our house because, as he told my mother, all our servants were Muslims.

Most of the Hindu families fled with whatever they could carry, leaving their homes, businesses and money and arriving in cities across the new border as refugees. My future in-laws, too, left. They were the well-known Karachi jewelers Bhojwani Brothers, a very wealthy family with a lot of gold, diamonds and silver jewelry. They left everything behind and moved to Bombay. I was told how one of my husband’s uncles would go to the airport every day, taking one of the family children with him, and put him or her on a plane. At the other end, someone from the family would go to the airport every day, not knowing what to expect, and bringing home whoever had been sent. My husband was 12 and he remembers being left at the airport, where he had to wait until there was a seat available on a plane to Bombay.

We were Hindus who stayed on

I do remember that there was a lot of rioting, looting and killing. Women were being raped and burnt, and their husbands killed. There was a violent incident in the house behind ours and my father had to intervene. We were protected because of a close friend of our family, a very powerful lawyer in the new government of Pakistan. He was A.K. Brohi, my mother’s brother’s best friend. My mother’s brother, Hiranand Sadhwani and he had been at law school together in Hyderabad. When my uncle was leaving Hyderabad, he told Brohi, ‘My sister is staying behind. Take care of her.’ And Brohi said, ‘Don’t worry. She is my sister too.’ So that day when there was this crisis in the house behind ours and an old man was being beaten up, my father went and rescued the family and hid them in our house and called Brohi for protection. After that, we had the Pakistan military guarding our house 24 hours a day for several months. Brohi was a family friend and visited us often, and so was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a friend from Hyderabad and another influential Muslim connection. We were all Sindhis and shared the love for Sindhi music, poetry, culture and our Sufis.

In all the years we lived in Pakistan, it never seemed particularly dangerous, though we were under constant surveillance, being a minority. And we were conscious that, being the only prominent Hindu family, we stuck out like a sore thumb, with our enormous house of marble, a swimming pool and huge garden. Muslim refugees who had arrived in Pakistan looking for a better life for themselves felt anger and resentment with our businesses and carpet factory.

People would walk past our house making loud threats. We had iron grill gates and I remember seeing men walking outside with stout sticks calling out, ‘Hindu people! We’ll come and get you out of this house!’ Many times I saw my father go out and talk to them diplomatically to calm their anger, but I’m sure it must have been quite tense till they put their sticks down and turned around and left, invariably threatening to return. He paid the price for being constantly under stress and carried the burden for us so we could live in safety and luxury. He faced threats and all kinds of very difficult situations, never showing any trace of his troubles, hiding everything from us, his family. Out of these circumstances he learnt to make many influential friends who protected us. He came to be well known and well-liked in spite of our religious differences. They just knew him as ‘Hotu Bhai’. We children grew up not fearing anybody or anything. When going to school if none of the family cars were available, I would just get into a rickshaw or a local bus. My mother would worry but we never felt unsafe in Pakistan after the initial looting and rioting settled down. There was no apparent fear of physical threat on the streets but in many subtle ways we were reminded we didn’t belong here. With the Hindus mostly all gone, our friends were Muslims, Christians or Parsis, but their religion was of no consequence; they were just our dear friends.

The upheaval in the two counties had worsened the poverty and scarcity and there was a constant threat of thieves which had nothing to do with a religious or political conflict. In well-off homes, everything was kept locked in closets and in trunks under the beds. That’s why the women of the family carried bunches of keys. We didn’t trust our servants. And burglaries were common. The thieves rubbed oil on their naked bodies and in the middle of the night would sneak in quietly to rob, the oil making them slippery and difficult to catch if spotted. I remember my cousin Ram once saw a thief right next to his bed in the dark. He leapt up to grab him but the man ran away, jumping over the wall of the house and escaping.

Apart from good clothes and expensive things, Bhaiband women always had their jewelry. They wore their gold and diamonds and loved to collect more and more. For a woman, that was her wealth. In those days, there wasn’t much banking and in any case, people didn’t understand banking. It felt a bit like somebody else was in control of your money. A married woman always wore bangles. The idea of giving jewelry to your daughter when she married was to give her security. So if she was ill-treated or fell on bad times, she had some security. It was quite common when a man suffered business losses, or if he wanted to quit his job and set up on his own, that his wife would offer him her jewelry to sell. Jewelry was very beautiful and a sign of status. It was a good business to have and there was always demand for it, which is why my husband’s family business, Bhojwani Brothers, had been so prosperous.

As time went by, Pakistan started getting more conservative. Women were wearing burqas—which was totally foreign to us. My cousins and I kept up with our nice clothes. We studied at the Karachi Grammar School, a British school, and wore dresses.

One of my cousins, Mangharam’s daughter, had married an Amil boy who was living in Bombay. His parents lived in Hyderabad and the match was arranged there. After their marriage, he took her to live in Bombay which to us in those days seemed as glamorous and fast-paced as London. Because of the convenience of having her to stay with, we spent our Christmas holidays there. I think our parents kept a foot in the door to make sure that we girls married Hindus. They stayed in touch, kept contact with distant relatives and introduced us to different Sindhi families.

_______________

Courtesy: Sahapedia

Click here for Part-I