Monica’s grandfather was the first in their family to go to Gibraltar. In those days, the men of their community left in shiploads and most of them were employed by Sindhis to work in their overseas shops.

Introduction

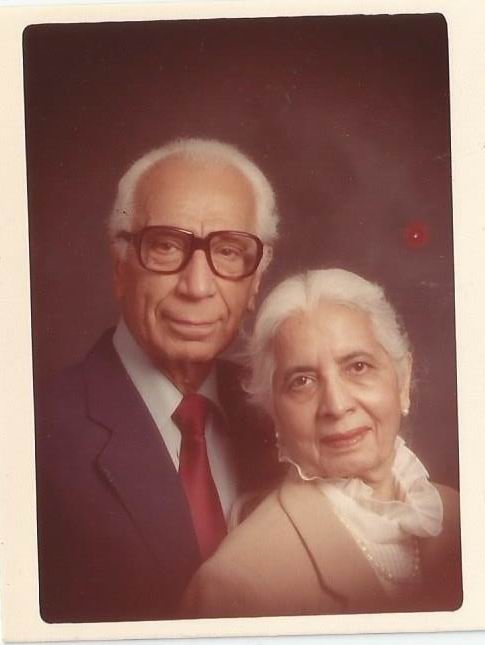

Monica Mahtani Bhojwani was born in a prisoner of war camp in France on November 22, 1940, and passed away on March 4, 2020 at the age of 79. She had an exciting story documented in her first book. Monica grew up in post-Partition Karachi. As a young bride, she moved to Gibraltar, where she and her husband Santu lived for ten years. After the subsequent twenty-five years in Las Palmas, they settled in USA to be near their children. Monica, who was never a typical Bhaiband woman, saw herself as an American Bhaiband. When she was young, she rebelled a little against forced traditions and found her own way of processing what she believed in and what she didn’t.

In this historically authentic account of some important events of her life, we get a sense of what it was like for the Bhaiband women of Sindh.

Gibraltar in the 1950s-60s

In 1957, after I finished school, I went to California as an exchange student. On my way back home, my parents received me at Southampton where the ship docked, and the three of us toured Europe together. At the end of it, my father took us to Gibraltar. Our family had business holdings there which were managed by our employees and every few years one of the brothers would make a visit to check on the accounts, the stocks and to stay in touch with the loyal employees.

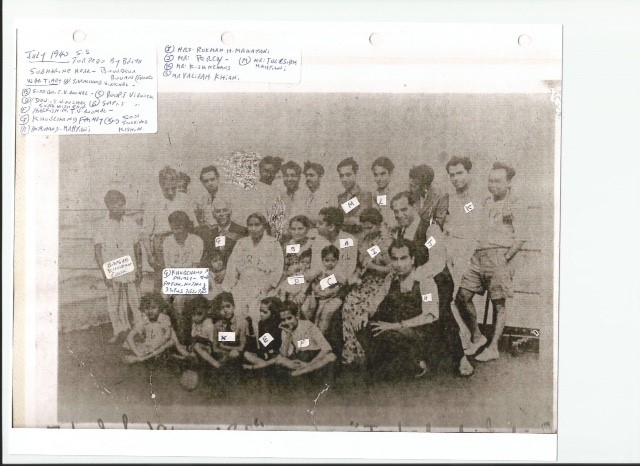

We stayed in Gibraltar for about three weeks. My parents had lived there years ago but still had many friends there. We were invited for parties and I got to know some of them. It was at this time that Santu and I first met. He was on his first Sindhwork trip and was looking after our shops.

My uncle Mangharam had met him in Bombay and took to him at once. He offered him a Sindhwork job as soon as he finished college. Santu was keen to study more but because of the family situation after Partition, he had no choice. His whole family, so well off in Karachi, had arrived in Bombay without anything and for quite a long time they survived on the largesse of the few relatives who had got there before.

My father-in-law was Nariandas Bassarmal Bhojwani and he worked together with his brothers. That’s the way it was in those days: in every joint family, the brothers worked together. My mother-in-law, Rukibai, had been a Hathiramani before marriage, another of the old aristocratic Bhaiband surnames. She had four daughters and then five sons and my husband, Santu, is the second son.

They lived together in a big house named Chandhiwalla Building in Dadar. They did get back into the jewelry business but without capital, and working against the already established jewelry cartels in Bombay, it was difficult. They realized that they could no longer maintain the standards of a joint family and gradually formed separate family units, each trying to make ends meet and get on with their own lives, and the joint family of so many generations broke up.

Santu was young, hardworking, and fit well into our family. He was not considered just one of the staff, being different from the rest; he was one of us. He had been handpicked by my uncle Mangharam with the idea of grooming him to take charge so that the brothers could take it easy and have someone trustworthy to manage the Gibraltar business.

We got married in Bombay in 1961, on Santu’s first visit home at the end of his first Sindhwork contract, as per Bhaiband tradition. But it was not a traditional Bhaiband wedding where the couples are introduced to each other a few days in advance and large dowries are handed over. Our parents had given us time to get used to the idea and develop our attachment to each other. And my mother-in-law was not after a dowry. Her daughters were already married and she didn’t have to collect money for their dowries. So my parents just gave us large gifts of cash which kept us comfortable with the good rates of interest we had in those days.

I was 20 years old and for me the Bhaiband life in Gibraltar was a new world, one in which what was important was how much money you had and what you were worth. I moved in with Santu to the firm’s house where the employees lived. We were there while our house in La Linea, just across the Spanish border, was being constructed. The flat was big and was run by the wives of the two managers.

They supervised the cooking and in the evenings we would all eat together when the men came home from the shops. One of the daily routines I remember was that every evening they had a hairdresser coming to the house. The women would get rollers put and when their hair was set they would get ready and the maid would serve them tea. They would then go down to Line Wall Boulevard where they would sit and chit-chat with the other Sindhi women until it was time to come back home for dinner. They invited me to join them and I did try going a few times but they were much older and in those days I spoke mostly only English, so felt out of place. Instead, I would buy a magazine from the bookstore and sit on the terrace and read by myself. I also spent time with the Pohoomals who at that time had three unmarried daughters with whom I got along with rather well. The eldest one married a Sindhi, the manager of Bhojsons in Gibraltar, and so our friendship got even stronger. We still keep in touch.

My uncle Mangharam was keen that I join the business to keep busy and not sit idle at home, and I was used to working as I had always gone to our stores in Karachi to help out after school. Our two stores specialized in French perfumes and cosmetics and also fine cashmere sweaters and silk stockings from England. These items were in great demand by the tourists and the naval officers as gifts to take back to their fashionable ladies. Gibraltar was a duty-free port making it tempting to shop a lot. But our staff resented having the boss’s daughter around. In any case, they all had their work laid out so there really wasn’t much I could do except rearrange and sort out the merchandise. This was not to my taste as I needed something more productive, so I quit.

About a year after I came to Gibraltar, two more young men got married and brought their wives with them so I had company of my age and station. Our generation was quite different from the older Bhaibands. Before that it was just the older women and they would mostly sit and gossip. Their husbands’ timings were terrible, money was just not enough, the children were becoming difficult, the newly-married younger generation had turned out so strange…there was quite a lot to complain about! Also, some of their husbands were cheating and everybody knew about it. Having lived here as bachelors, they had girlfriends across the nearby border in Spain. So maybe they talked about that too.

Once a week, us younger ones would get together to play rummy. And then there was the dressing up, the shopping, and an underlying competitive feeling to all that we did. This was our little world on the Rock, an area of two square miles. When our friends travelled they would bring things from India and show off. Or ask each other ‘What did your parents send?’ and compare it with what someone else’s parents had sent. Then it became, ‘I got this from Hong Kong!’ and everyone wanted things from Hong Kong. Then French chiffons became fashionable. It went on and on. This was the life of a Sindhworki Bhaiband woman. When I look back, it surprises me how we managed to survive with so little intellectual stimulation.

Just because of who I was

In Gibraltar, we had a strict social hierarchy, and though I had not married a rich man I was included with the in crowd without doing anything, just because of who I was. My family members had been here for generations and were owners, not employees. There was this unspoken feeling that the ones who were not from Hyderabad or Karachi, the ones who had come later and their families belonged to Sukkur or Sehwan or other places in Sindh, were just not equal.

The oldest to settle in Gibraltar were the Poohumals, Dialdas, Khemchand, the Khubchands and a few more families. Kishin Khubchand had been a little boy on the Kemmendine when it went down. He lost his entire family that day and my mother took him under her wing and cared for him like a son. He was and still is like a brother to me. There was also the Carlos family. We all had our stores on Gibraltar’s Main Street. Carlos is of course a Spanish name; many of the early Sindhis took up local names. Nobody could pronounce my uncle Mangharam’s name so he had been Don Miguel to the locals.

I was somewhat pampered in Gibraltar because of surviving the shipwreck. All the Indians who were on that fateful Kemmendine voyage were from Gibraltar. In the prison camp, people knew that my mother was expecting and they would give her little gifts from their cigarette money. She in turn would ask the German guard to go and buy vegetables and she would cook for them. This was something they all remembered with warmth and gratitude. I was born there and the only baby in the camp. Anywhere I went, they reminded me that we had all been together in occupied France, and this created a special bond between us. My friends who were new to Gibraltar would wonder why I was getting special attention. Even Kishin used to tease my husband, telling him ‘I picked your wife up in my arms before you did!’

As time went by

As time went by, our families had children and the children grew up. We formed a little India Club where we’d have birthday parties and celebrations. We all became very close, and our children too. About ten years after we got married, my husband and I decided to leave and venture out on our own. We first moved to Canada but that didn’t work out, and we chose to settle in Las Palmas, Spain, where there was a fair-sized Indian community and the lifestyle was what we had got used to. We opened a perfume store, a business we understood, and ran it for 25 years.

The Sindhi Bhaiband women had a routine of taking care of the children, sending them to school and cooking two meals for the family. Here it was a custom to have two main meals. Fortunately it was possible to get Spanish women as house help for the heavy cleaning. After lunch was ‘Siesta’ where everyone rested, after all, we were in Spain. Then the men would leave for their evening shift and the women, depending on their circumstances, would either stay at home with the children or go to satsangs (religious meetings) or play cards in their individual groups. I somehow did not take to these activities and spent the evenings with my three children and seeing to their homework. Their schooling was in Spanish but I wanted them to be fluent in English, more of a world language, and the one I was most comfortable with.

As our children graduated, the two older girls left to study in Canadian universities and our son went to a boarding school in England. Many families sent their sons to England to better prepare them for the business world. Now I had time on hand and, longing to be productive in some way, decided to join my husband in our perfume store. We worked together for about 13 years until one day a potential Sindhi buyer approached us with the offer to buy out our business. Santu was tired of retail, and our children had grown up and left home. It was time to wind down. We negotiated and ended up making a deal and selling. So in 1996, after 25 years in Las Palmas, we began our move to the US to be closer to our children.

We often think of our years spent there with sweet memories, but are happy here in our comfortable home and, with our two daughters just two minutes away and two grown grandchildren to relish, we are all together again. (Concludes)

______________________

Courtesy: Sahapedia

Click here for Part-I, Part-II