By the end of January 1948 there were about 40,000 Hindus in Karachi waiting for passage to India, and many more in the hinterland.

Chief Minister Khuhro imposed a permit system on 15 February 1948, whereby no Hindu could leave his or her town of origin without a permit issued by the local authorities.

By Nandita Bhavnani

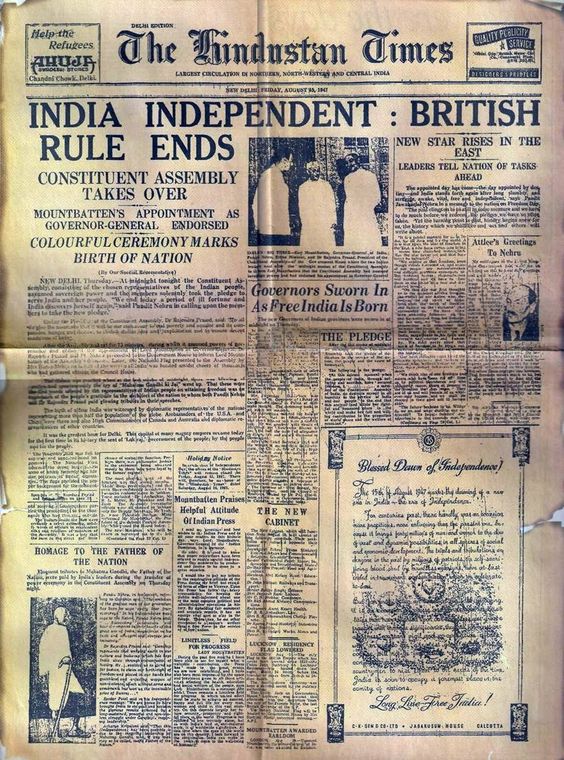

Exodus from Sindh

…Narayandas Malkani was then a 57-year-old Congress worker, who had worked closely with Gandhi in Delhi’s Bhangi Colony. He had narrowly escaped being attacked during the Karachi pogrom. After this, he and Govardhan Vazirani, secretary of the Congress, were deputed to fly to Delhi to convince the Congress high command to evacuate Hindus from Sindh. Narayandas Malkani recalls:

“On arrival, I met Gandhiji and other senior leaders and I told them face to face about the Karachi riots. I was there for a week, and I met everyone about two or three times. Pandit Nehru told me to go meet Bajpayee, the secretary general in the main office. I met him, and I briefed him about the conditions in Sindh; I told him that the time had now come for the Hindus to be evacuated from Sindh and resettled in India by the government. He listened to everything attentively and then I took his leave.

“Finally Vazirani and I came to the conclusion that our work was done and that we could return to Karachi by air the next morning that is 31 January. Before returning, I went to meet Gandhiji for the fourth and last time, to take his leave. It was about four in the evening, and he was sitting outside Birla House in the sun, with a straw hat on his head.

“His voice was not weak any longer, and his bare body shone, burnt in the sun. When I rose to touch his feet and take his leave, he clapped me firmly on my back. This clap on the back used to be his blessing. He said, ‘Now you go and evacuate people from Sindh. You leave only after evacuating everyone else. Make sure you don’t leave before that. Give Mr. Khuhro a message that I will come to Sindh and make efforts towards securing peace in Sindh. But for that, he will have to take Mr. Jinnah’s permission and send me a telegram.’”

“His voice was not weak any longer, and his bare body shone, burnt in the sun. When I rose to touch his feet and take his leave, he clapped me firmly on my back. This clap on the back used to be his blessing. He said, ‘Now you go and evacuate people from Sindh. You leave only after evacuating everyone else. Make sure you don’t leave before that. Give Mr. Khuhro a message that I will come to Sindh and make efforts towards securing peace in Sindh. But for that, he will have to take Mr. Jinnah’s permission and send me a telegram.’”

Malkani used to stay with Gandhi’s son, Devdas, whenever he visited Delhi. Shortly after he returned to Devdas Gandhi’s home, they were informed of Gandhi’s assassination. A grieving and distraught Malkani flew back to Karachi the next day, where he was astonished to find that staff from the Indian High Commission had come to receive him in a car, and that he had been appointed additional deputy high commissioner in Karachi, specifically for the purpose of evacuating Hindus and Sikhs from Sindh. Malkani supervised the work of evacuation in Karachi and Hyderabad, by turns, and also toured other towns in Sindh, to assess the situation of the Hindus there.

Special trains were run from Hyderabad and Mirpur Khas to Pali and Marwar Junction in present day Rajasthan, where refugee camps were set up. These trains went directly – and safely – from Sindh to Rajasthan and had no need to traverse Punjab, with its history of violence. Moreover, the organized evacuation of Hindu and Sikh refugees from West Punjab by rail had been completed by the first week of December 1947, and now the Indian government could divert its attention and resources towards refugees from Sindh.

Owing to the determined intervention of the Indian government, and the assistance of Sri Prakasa, the Sindh government was obliged to facilitate the relatively smooth departure of non-Muslims from the province. The Sindh government announced that there would be no more searches of women among the departing Hindus and Sikhs.

Owing to the determined intervention of the Indian government, and the assistance of Sri Prakasa, the Sindh government was obliged to facilitate the relatively smooth departure of non-Muslims from the province. The Sindh government announced that there would be no more searches of women among the departing Hindus and Sikhs.

Also, a large number of Hindu government employees now wanted to either resign or to go on leave. The Sindh government relaxed its rules, permitting these employees to withdraw advances from their provident fund, and granted them long leave, thus enabling them to escort their families to India.

The Sindh government was keen to avoid congestion in Karachi of Hindu emigrants from the interior of Sindh: by the end of January 1948 there were about 40,000 Hindus in the city waiting for passage to India, and many more in the hinterland. In order to control and slow down the passage of Sindhi Hindus through Karachi, and so minimize chances of renewed violence, [Chief Minister] Khuhro imposed a permit system on 15 February 1948, whereby no Hindu could leave his or her town of origin without a permit issued by the local authorities. While this was meant to preserve law and order, it only caused greater distress to the Hindus, impatient to leave.

More often than not, local officials demanded bribes in order to issue permits. Sri Prakasa [India’s High Commissioner in Pakistan] recalls the flood of Sindhi Hindus who came to his office, requesting permits to travel to India:

“In the office of the High Commission, we had to encounter heavy crowds. It was difficult to regulate them. Everyone wanted to get a permit as soon as possible so that he could go away. Everyone wanted to reach India […] as soon as possible.

“The High Commission, however, had to act warily and to keep all practical considerations in view. We could give permits at a time only to as many persons as could be provided with trans-port. Even this tragic scene was not without its lighter side.

“One day I was looking after the arrangements myself. A woman came up to me and quietly told me that a particular young lady of her family was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. The child may be born any day. In these circumstances, would I think of giving priority to her? I did so; but the very next day, a strange scene presented itself before me. I found that all women suddenly found themselves in an advanced stage of pregnancy!

“They came to know that the High Commissioner was partial to women in that condition, and was willing to treat them with particular consideration. They thus found a good opportunity of saying that all of them were in the self-same condition. It was obviously impossible for the High Commissioner to get them medically examined!

“I had smilingly to tell them that I did not think it was possible that all of them would suddenly find themselves in such a delicate condition, and I was therefore compelled to give these permits in the ordinary course without making any distinctions between one person and another.”

Sindh emptied of minorities

By the middle of June 1948, 1000,000 Hindus had been able to migrate to India; 4,00,000 more remained in Sindh. In August 1949, there were incidents of renewed communal violence in Shikarpur and Sukkur, giving new impetus to the exodus. Evacuation continued for three whole years, finally tapering off in 1951. By this time, the transit camp set up at Karachi still had 644 evacuees waiting to leave, but Sindh was largely emptied of its Hindus: It was estimated that a scant 150,000 to 200,000 remained in their home province.

Sri Prakasa tells us, ‘On my tours in the interior, I saw what appeared to have been flourishing townlets before, complete with houses, temples, fields, now entirely deserted, the whole of the population – evidently all Hindu – gone to the last man.’

Yet, it should be noted that the stream of Hindus fleeing Sindh only thinned down to a trickle by 1951, and never dried up entirely. There has been a continuous migration of Sindhi Hindus from Pakistan to India from the 1950s to the present day, varying in intensity over the decades.

Here is the narrative of a Sindhi Hindu’s departure in 1949, which depicts the large crowds still in the process of migrating to India. Kirat Babani, the prominent Sindhi author and journalist, was a young man of 25 in 1947, working with the Communist Party in Karachi. He and his other Communist friends decided not to migrate, but many of them were arrested in 1948. Babani was jailed for 11 months and released on the condition that he would be externed from Karachi.

Later, in 1949, he thought he would visit his family, which had migrated to India, and then return to Sindh. When he boarded the ship at the Keamari docks, government officials searched his belongings extremely roughly, and then served him a legal notice of exile from Pakistan. He recounts his departure from Sindh in his autobiography:

“Evening has fallen as I sit on the empty steel trunk. I have no idea when the ship weighed anchor and set sail towards its destination. My belongings are still scattered around me, and there, on the entire deck, people are scattered. Entire families, mostly from villages in the interior of Sindh, have been thrown here.

“They are from the poor and middle class, their dress and behavior is Sindhi. Some mothers also have suckling children with them, whom they are nursing, covered with their dupattas, and with their backs to the men. This transgression of custom must cause them mental agony. […]

As night falls gradually, and as the ship starts to careen up and down and sideways like a rocking horse, subjected to the blows of the forceful waves of the deep sea, the condition of the travellers on deck begins to worsen. Many begin to feel dizzy and their stomachs start to churn. Many are retching, and some are actually vomiting. The crying and wailing of the children has cast a pall of gloom everywhere.”

(Excerpted from ‘The Making of the Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India’ by Nandita Bhavnani)

_________________________

Courtesy: Scroll (Published on July 26, 2014)