In 1916, Jinnah declared that India was “not to be governed by Hindus, and … it [was] not to be governed by the Muslims either, or certainly not by the English. It must be governed by the people and the sons of this country.”

Sanjeev Chopra and Atul Singh

Many scholars have spilled much ink on Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. A giant has now waded into the fray and penned a masterpiece.

Ishtiaq Ahmed is a professor emeritus at Stockholm University who first made his name with a path-breaking book, ‘The Pakistan Garrison State: Origins, Evolution, Consequences’. He then went on to pen the award-winning “The Punjab Bloodied Partitioned and Cleansed,” a tour de force on the partition of Punjab in 1947. Now, Ahmed has published “Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History,” a magisterial 800-page tome on Pakistan’s founder. This book is published by Penguin Random House. The same book is published in Pakistan by Vanguard Books.

Ahmed is a meticulous scholar who has conducted exhaustive research on the writings and utterances of Jinnah from the moment he entered public life. Pertinently, Ahmed notes the critical moments when Jinnah “spoke” by choosing to remain quiet, using silence as a powerful form of communication. More importantly, Ahmed has changed our understanding of the history of the Indian subcontinent.

Setting the Record Straight

Until now, scholars like Stanley Wolpert, Hector Bolitho and Ayesha Jalal have painted a pretty picture of Jinnah, putting him on a pedestal and raising him to mythical status. Wolpert wrote, “Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah did all three.” Both Wolpert and Bolitho argued that Jinnah created Pakistan. Jalal has argued that “Jinnah did not want Partition.” She claims Jinnah became the sole spokesman of Muslims and the Congress Party forced partition upon him.

Jalal’s claim has become a powerful myth on both sides of the border. In this myth, the Congress in general and India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in particular opted for partition instead of sharing power with the Muslim League and Jinnah. Jalal makes the case that “Punjab and Bengal would have called the shots” instead of Uttar Pradesh, making the emergence of the Nehru dynasty impossible. Her claim that “the Congress basically cut the Muslim problem down to size through Partition” has cast Jinnah into the role of a tragic hero who had no choice but to forge Indian Muslims into a qaum, a nation, and create Pakistan.

The trouble with Jalal’s compelling argument is that it is not based on facts. She fails to substantiate her argument with even one of Jinnah’s speeches, statements or messages. Ahmed’s close examination of the historical record demonstrates that Jinnah consistently demanded the partition of British India into India and Pakistan after March 22, 1940. Far from the idea of Nehru forcing partition on a reluctant Jinnah, it was an intransigent Jinnah who pushed partition upon everyone else.

The trouble with Jalal’s compelling argument is that it is not based on facts. She fails to substantiate her argument with even one of Jinnah’s speeches, statements or messages. Ahmed’s close examination of the historical record demonstrates that Jinnah consistently demanded the partition of British India into India and Pakistan after March 22, 1940. Far from the idea of Nehru forcing partition on a reluctant Jinnah, it was an intransigent Jinnah who pushed partition upon everyone else.

Ahmed goes on to destroy Jalal’s fictitious claim that Nehru engineered the partition of both Punjab and Bengal to establish his dynasty. Punjab’s population was 33.9 million, of which 41% was Hindu and Sikh. Bengal’s population was 70.5 million, of which 48% was Hindu. The population of United Provinces (UP), modern-day Uttar Pradesh, was 102 million, of which Hindus formed an overwhelming 86%. When Bihar, Bombay Presidency, Madras Presidency, Central Provinces, Gujarat and other states are taken into account, the percentage of the Hindu population was overwhelming. In 1941, the total Muslim population of British India was only 24.9%. This means that Nehru would have become prime minister even if India had stayed undivided.

Ahmed attests another fact to buttress his argument that Nehru’s so-called dynastic ambitions had nothing to do with the partition. When Nehru died, Gulzarilal Nanda became interim prime minister before Lal Bahadur Shastri took charge. During this time in power, Nehru did not appoint Indira Gandhi as a minister. It was Kumaraswami Kamaraj, a Congress Party veteran, and other powerful regional satraps who engineered the ascent of Indira Gandhi to the throne. These Congress leaders believed that Nehru’s daughter would be weak, allowing them greater say over party affairs than their eccentric colleague Morarji Desai. Once Indira Gandhi took over, she proved to be authoritarian, ruthless and dynastic. By blaming the father for the sins of the daughter, Jalal demonstrates that she neither understands India’s complex demography nor its complicated history.

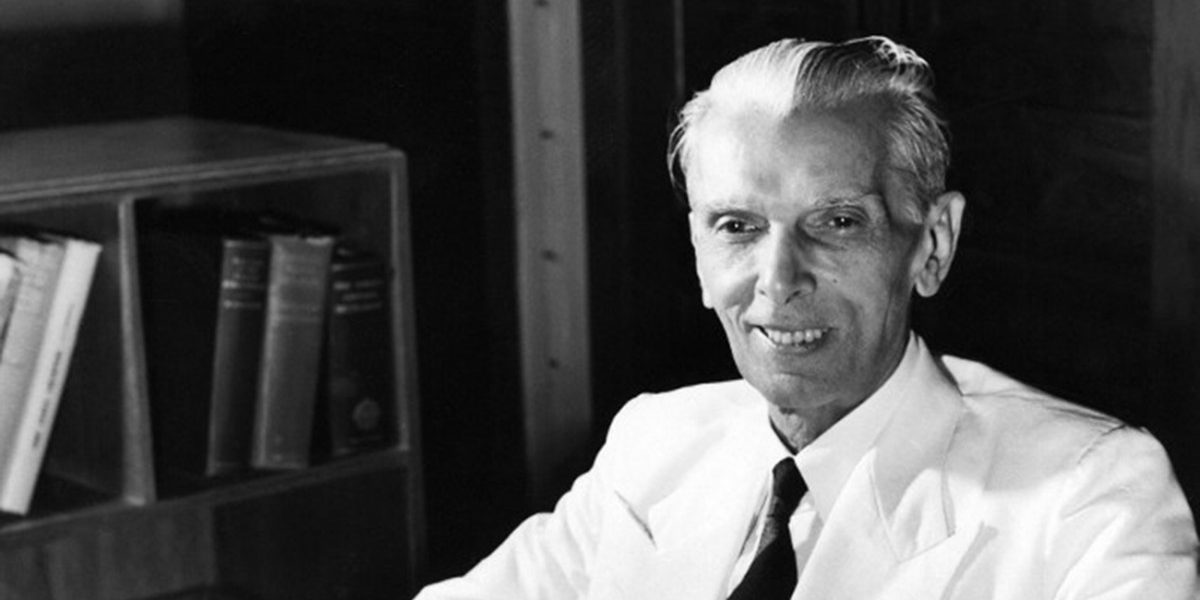

To get to “the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” about India’s partition, we have to read Ahmed. This fastidious scholar analyzes everything Jinnah wrote and said from 1906 onward, the year Pakistan’s founder entered into public life. Ahmed identifies four stages in Jinnah’s career. In the first, Jinnah began as an Indian nationalist. In the second, he turned into a Muslim communitarian. In the third, Jinnah transformed himself into a Muslim nationalist. In the fourth and final stage, he emerged as the founder of Pakistan where he is revered as Quaid-i-Azam, the great leader, and Baba-i-Qaum, the father of the nation.

Ahmed is a political scientist by training. Hence, his analysis of each stage of Jinnah’s life is informed both by historical context and political theory. Jinnah’s rise in Indian politics occurred at a time when leaders like Motilal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Subhas Chandra Bose were also major players in India’s political life and struggle for freedom. Jinnah’s role in the tortured machinations toward dominion status and then full independence makes for fascinating reading. Ahmed also captures the many ideas that impinged on the Indian imagination in those days from Gandhi’s nonviolence, Jinnah’s religious nationalism and Nehru’s Fabian socialism.

Jinnah’s Tortured Journey

As an Indian nationalist, Jinnah argued that religion had no role in politics. His crowning achievement during these days was the 1916 Lucknow Pact. Together with Congress leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Jinnah forged a Hindu-Muslim agreement that “postulated complete self-government as India’s goal.” That year, Jinnah declared that India was “not to be governed by Hindus, and … it [was] not to be governed by the Muslims either, or certainly not by the English. It must be governed by the people and the sons of this country.” Jinnah advocated constitutionalism, not mass mobilization, as a way to achieve this ideal.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed at the end of World War I, Indian Muslims launched a mass movement to save this empire. Among them was Jinnah who sailed to England as part of the Muslim League delegation in 1919 to plead that the Ottoman Empire not be dismembered and famously described the dismemberment of the empire as an attack on Islam.

As an Indian nationalist, Jinnah argued that religion had no role in politics.

To support the caliph, Indian Muslim leaders launched the Khilafat Movement. Soon, this turned into a mass movement, which Gandhi joined with much enthusiasm. Indian leaders were blissfully unaware that their movement ran contrary to the nationalistic aspirations of Turks and Arabs themselves.

Later, Islam would emerge as the basis of a rallying cry in Indian politics. The nationalist Jinnah started singing a different tune: He argued that Muslims were a distinct community from Hindus and sought constitutional safeguards to prevent Hindu majoritarianism from dominating. In the 1928 All Parties Conference that decided upon India’s future constitution, Jinnah argued that residuary powers should be vested in the provinces, not the center, in order to prevent Hindu domination of the entire country. Ahmed meticulously documents how the British used a strategy of divide and rule, ensuring that the chasm between the Congress and the Muslim League would become unbridgeable.

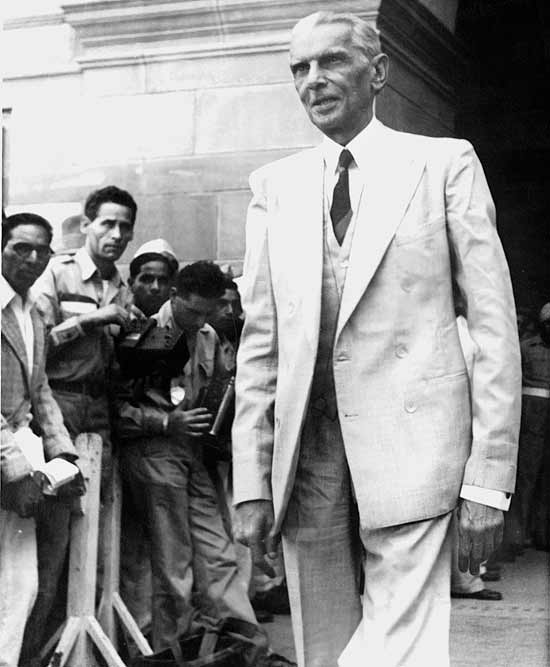

As India turned to mass politics under Gandhi, Jinnah retreated to England. After a few quiet years there, he returned to India in 1934 and was elected to the Central Legislative Assembly, the precursor to the parliaments of both India and Pakistan. Jinnah argued that there were four parties in India: the British, the Indian princes, the Hindus and the Muslims. He took the view that the Congress represented the Hindus while the Muslim League spoke for the Muslims.

As India turned to mass politics under Gandhi, Jinnah retreated to England. After a few quiet years there, he returned to India in 1934 and was elected to the Central Legislative Assembly, the precursor to the parliaments of both India and Pakistan. Jinnah argued that there were four parties in India: the British, the Indian princes, the Hindus and the Muslims. He took the view that the Congress represented the Hindus while the Muslim League spoke for the Muslims.

Also read: A Book That Busts Many Myths Surrounding Jinnah

Importantly, Jinnah now claimed that no one except the Muslim League spoke for the Muslims. This severely undercut Muslim leaders in the Congress. Jinnah had a visceral hatred for the erudite Congress leader Azad, who was half Arab and a classically-trained Islamic scholar with an encyclopedic knowledge of the Quran, the hadith and the various schools of Islamic thought. Furthermore, Azad’s mastery of the Urdu language stood unrivaled. He wrote voluminously in this pan-national Muslim lingua franca. In contrast, Jinnah was an anglicized lawyer who wrote in English and spoke poor Urdu.

Jinnah’s argument that the Muslim League was the only party that could represent Muslims was not only conceptually flawed, but also empirically inaccurate. Muslims in Bengal, Punjab, Sindh and the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) supported and voted for regional political parties, not the Muslim League. In fact, voters gave the Muslim League a drubbing in 1937. This hardened Jinnah’s attitude, as did the mass contact program with Muslims that the Congress launched under Nehru. When the Congress broke its gentleman’s agreement with the Muslim League to form a coalition government in United Provinces (UP) after winning an absolute majority, Jinnah turned incandescent.

Jinnah’s argument that the Muslim League was the only party that could represent Muslims was not only conceptually flawed, but also empirically inaccurate. Muslims in Bengal, Punjab, Sindh and the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) supported and voted for regional political parties, not the Muslim League. In fact, voters gave the Muslim League a drubbing in 1937. This hardened Jinnah’s attitude, as did the mass contact program with Muslims that the Congress launched under Nehru. When the Congress broke its gentleman’s agreement with the Muslim League to form a coalition government in United Provinces (UP) after winning an absolute majority, Jinnah turned incandescent.

In retrospect, the decision of the Congress to go it alone in UP was a major blunder. After taking office, the Congress started hoisting its flag instead of the Union Jack and disallowed governors from attending cabinet meetings. Many leaders of the Muslim League joined the Congress, infuriating Jinnah. He drew up a list of Congress actions that he deemed threatening to Islam. These included the Muslim mass contact campaign, the singing of Vande Mataram, Gandhi’s Wardha Scheme of Basic Education and restrictions on cow slaughter. Jinnah came to the fateful decision that he could no longer truck with the Congress and the die was cast for a dark era in Indian history.

Click here to read full article

_________________

Courtesy: Courtesy: Fair Observer