Seven Hausa kingdoms flourished between the Niger River and Lake Chad, of which the Emirate of Kano was probably the most important.

Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker

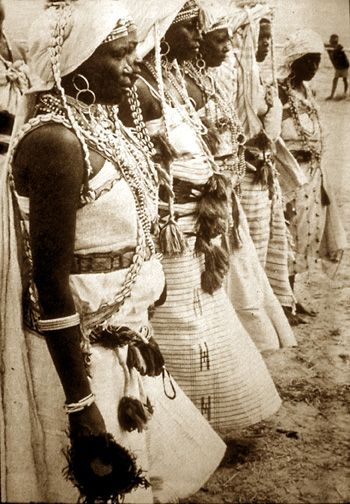

In West Africa, the Hausa people are located in Nigeria, Benin, Niger, Cameroon and Ghana. The Hausa are a Sahelian people chiefly located in the West African regions of northern Nigeria and southeastern Niger. There are also significant numbers found in northern regions of Benin, Ghana, Niger, Cameroon, and in smaller communities scattered throughout West Africa and on the traditional Hajj route from West Africa, moving through Chad, and Sudan. Many Hausa have moved to large coastal cities in West Africa such as Lagos, Accra, or Cotonou, as well as to countries such as Libya, in search of jobs that pay cash wages.

In the twelfth century, the Hausa were a major African power. Seven Hausa kingdoms flourished between the Niger River and Lake Chad, of which the Emirate of Kano was probably the most important. According to legend, its first king was the grandson of the founder of the Hausa states. There were 43 Hausa rulers of Kano until they lost power in 1805. Historically, these were trading kingdoms dealing in gold, cloth, and leather goods. The Hausa people speak the Hausa language which belongs to the Chadic language group, a sub-group of the larger Afro-Asiatic language family, and has a rich literary heritage dating from the fourteenth century.

The Hausa are a major presence in Nigerian politics. The Hausa people are heirs of a civilization that has flourished for over a thousand years in West Africa. The Hausa also have an architectural legacy represented by the Gidan Rumfa, or Emir’s palace in Kano at the center of what is the economic capital of Nigeria and the remains of the old walls around the city. Thus, culture deserves a wider exposure outside of West Africa, since it testifies to the existence of a sophisticated, well organized society that predates the arrival of the European colonizers, who saw little if anything admirable, interesting, cultured or civilized in what they persisted in calling “the Black continent.” The traditional homeland of the Hausa was an early location for French and British interests, attracted by the gold deposits and the possibility of using the Niger for transport. Some of the earliest British explorers in Africa, such as Mungo Park and Alexander Gordon Laing gravitated to the Niger. Little thought was given to the preservation of indigenous culture or systems, although Mary Henrietta Kingsley, who also explored this region, championed the African cause.

In 1810, the Fulani, another Islamic African ethnic group that spanned across West Africa, invaded the Hausa states. Their cultural similarities, however, allowed for significant integration between the two groups, who in modern times are often demarcated as “Hausa-Fulani,” rather than as individual groups, and many Fulani in the region do not distinguish themselves from the Hausa.

The Hausa remain preeminent in Niger and northern Nigeria. Their impact in Nigeria is paramount, as the Hausa-Fulani amalgamation has controlled Nigerian politics for much of its independent history. They remain one of the largest and most historically grounded civilizations in West Africa. Although many Hausa have migrated to cities to find employment, many still live in small villages, where they grow food crops and raise livestock on nearby lands. Hausa farmers time their activities according to seasonal changes in rainfall and temperature.

Hausa have an ancient culture that had an extensive coverage area, and long ties to the Arabs and other Islamized peoples in West Africa, such as the Mandé, Fulani, and even the Wolof of Senegambia, through extended long distance trade. Islam has been present in Hausaland since the fourteenth century, but it was largely restricted to the region’s rulers and their courts. Rural areas generally retained their animist beliefs and their urban leaders thus drew on both Islamic and African traditions to legitimize their rule. Muslim scholars of the early nineteenth century disapproved of the hybrid religion practiced in royal courts, and a desire for reform was a major motive behind the formation of the Sokoto Caliphate. It was after the formation of this state that Islam became firmly entrenched in rural areas. The Hausa people have been an important vector for the spread of Islam in West Africa through economic contact, diaspora trading communities, and politics. Originally from West Africa, they have lived in Sudan for centuries, often settling there on the long and arduous land journey to or from Mecca for the Hajj. All Muslims who are able to do so should try to visit the holy city in Saudi Arabia at least once in their lifetime to perform the pilgrimage. British colonisers in Nigeria were also responsible for the movement of many Hausas eastwards – when they defeated the defiant sultan of the Sokoto Caliphate in 1903, many of his followers and descendants eventually settled in Sudan. Sudanese Hausa singer Aisha al-Falatiya was hugely popular from the 1940s onwards

Estimates about their population today vary wildly. At independence in 1956 it was thought to be 500,000 – and now ranges from three to 10 million out of Sudan’s more than 44 million residents.

They tend to live and work in central Sudan in agricultural schemes and farms along Sudan’s rivers – but most cities around the country have Hausa communities. Their influence on Sudanese culture cannot be underestimated – and can be smelt at open air markets and eating places across the country. This is because their Agashe dish is a beloved street food: grilled kebabs of beef, lamb or chicken seasoned with spices and peanuts and served with raw onions and lime juice. The first woman to sing on national radio in Sudan in 1942 was Aisha al-Falatiya, a Sudanese Hausa singer who became hugely popular with her love songs – as well as those with political themes, especially in the run-up to independence. She also toured the continent during World War II entertaining Sudanese troops fighting for the British, yet Hausas sometimes find it hard to gain acceptance within Sudanese society. The Hausas have long struggled with alienation… and they tired of being called foreigners, during colonial times, the British created one of the world’s largest irrigation schemes between the Blue Nile and White Nile. When the Gezira project started in 1911, slaves were largely used as free labor to mainly grow cotton for the industrial mills of north-west England.

Sudan after the British abolished slavery in the region in 1924, Gezira – which today has expanded to an area of more than two million acres (more than 900,000 hectares) – faced a manpower shortage.

The colonial administration came up with was to give 3,000 Hausa people land to encourage them to settle – with many of them working on the Gezira scheme. This allowed a sizeable community of Hausa people to put down more permanent roots, but right from the start, local groups were unhappy and stipulated that the land could not be handed down to younger generations. This was followed in 1948 with a restrictive citizenship law.

The Hausas were denied citizenship status based on their ethnicity by the Sudanese authorities with the complicity of the British administration, which resulted in denying them education, and other opportunities.

The country’s independence eight years later, things did not improve greatly – as a person had to show their great-great grandfather was Sudanese to get citizenship, which many Hausas were unable to do. This changed for the better in 1994 when Islamist politician Hassan Turabi was speaker of parliament, and ushered in a law that allowed those born in Sudan or had lived in the country for five years to get Sudanese nationality. The Hausas still face prejudice from officials who sometimes require a Hausa person to bring four witnesses to swear they are Sudanese – and generally make it difficult for them to get papers.

The trouble last weekend was not the first backlash they have faced. Student protests in the capital, Khartoum, against a peace deal ending a civil war in the south turned violent in 1974. One of those killed by police was a boy from a community with links to West Africa. It gave rise to the authorities’ belief that these communities, including the Hausas, were behind the opposition protests – and some of them were expelled from Khartoum and its twin city Omdurman.

The Hausa resident of Omdurman at the time, several suburbs were targeted with people regarded as foreigners rounded up and put on trains to Nyala in South Darfur. Trouble also erupted in October 2008 when Omar al-Bashir was president. He was quoted by a paper as saying that the Hausa community was not indigenous to Sudan, leading to protests in which seven died and more than 100 people were wounded. Bashir denied making the comments. It is complicated – and again goes back to land and is also mixed up with political infighting for influence in the state. Last month, a new governor of Blue Nile granted a Hausa request for their own emirate within the state, which gives them the recognition they want and a say over local affairs. The Gezira project is considered one of the world’s largest irrigation schemes, the move irked the state’s main traditional ruler, from the Berta ethnic group – who suggested that the Hausa community get a lower tier of recognition instead, with their leader becoming a mayor or sheikh.

This led to calls on social media to strip Hausa people of their citizenship and their agricultural land – and the new emir was even kidnapped, sparking the recent violence. Each side is backed by different factions of Blue Nile’s SPLM-N movement and former rebel group – one of which recently agreed to give up its arms, while the other still refuses. The SPLM-N squabbles have left the Hausa community more determined than ever to get the governor to keep his promise and create their emirate. Such divisions could play into the hands of the country’s military leaders – and may even be encouraged by them. There are fears they are eager to take the steam out of continuing nationwide protests against last October’s coup when the army overturned a power-sharing arrangement with civilian groups intended to pave the way to elections next year.

Language The best known of the northern peoples, often spoken of as coterminous with the north, are the Hausa. The term refers also to a language spoken indigenously by savanna peoples spread across the far north from Nigeria’s western boundary eastward to Borno State and into much of the territory of southern Niger. The core area lies in the region in the north and northwest where about 30 percent of all Hausa could be found. It also includes a common set of cultural practices and, with some notable exceptions, Islamic emirates that originally comprised a series of centralized governments and their surrounding subject towns and villages.

These pre-colonial emirates were still major features of local government. Each had a central citadel town that housed its ruling group of nobles and royalty and served as the administrative, judicial, and military center of these states. Traditionally, the major towns were also trading centers; some such as Kano, Zaria, or Katsina were urban conglomerations with populations of 25,000 to 100,000 in the nineteenth century. They had central markets, special wards for foreign traders, complex organizations of craft specialists, and religious leaders and organizations. They administered a hinterland of subject settlements through a hierarchy of officials, and they interacted with other states and ethnic groups in the region by links of warfare, raiding, trade, tribute, and alliances.

The rural areas remained in 1990 fundamentally small to medium-sized settlements of farmers ranging from 2,000 to 12,000 persons. Both within and spread outward from the settlements, one-third to one-half the population lived in hamlet-sized farm settlements of patri-local extended families, or gandu, an economic kin-based unit under the authority and direction of the household head. Farm production was used for both cash and subsistence, and as many as two-thirds of the adults also engaged in off-farm occupations.

Throughout the north, but especially in the Hausa areas, over the past several centuries Fulani cattle-raising nomads have migrated westward, sometimes settling into semi sedentary villages. Their relations with local agriculturalists generally involved the symbiotic trading of cattle for agricultural products and access to pasturage. Conflicts arose, however, especially in times of drought or when population built up and interethnic relations created pressures on resources. These pressures peaked at the beginning of the nineteenth century and were contributing factors in a Fulani-led intra-Muslim holy war and the founding of the Sokoto Caliphate.

Throughout the north, but especially in the Hausa areas, over the past several centuries Fulani cattle-raising nomads have migrated westward, sometimes settling into semi sedentary villages. Their relations with local agriculturalists generally involved the symbiotic trading of cattle for agricultural products and access to pasturage. Conflicts arose, however, especially in times of drought or when population built up and interethnic relations created pressures on resources. These pressures peaked at the beginning of the nineteenth century and were contributing factors in a Fulani-led intra-Muslim holy war and the founding of the Sokoto Caliphate.

Fulani leaders took power over the Hausa states, intermarried with the ruling families and settled into the ruling households of Hausaland and many adjacent societies. By the twentieth century, the ruling elements of Hausaland were often referred to as Hausa-Fulani. Thoroughly assimilated into urban Hausa culture and language but intensely proud of their Fulani heritage, many of the leading “Hausa” families in 1990 claimed such mixed origins. In terms of local traditions, this inheritance was expressed as a link to the conquering founders of Sokoto and a zealous commitment to Islamic law and custom.

Centralized government in the urban citadels along the southern rim of the desert has encouraged long-distance trade over the centuries, both across the Sahara and into coastal West Africa after colonial rule moved forcefully to cut the trans-Saharan trade, forcing the north to use Nigerian ports. Ultimately, this action resulted in enclaves of Hausa traders in all major cities of West Africa, linked socially and economically to their home areas.

In summary, Hausa is both an ethnic group and a language; in contemporary usage the term refers primarily to the language. Linked culturally to Islam, Hausa are characterized by centralized emirate governments, Fulani rulers since the early nineteenth century, extended households and agricultural villages, trade and markets, and strong assimilative capacities. For these reasons, Hausa cultural borders have been constantly expanding. Given modern communications, transportation, and the accelerating need for a lingua franca, Hausa was rapidly becoming either the first or second language of the entire northern area of the country.

________________

Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker is a poet and writer from Omdurman Umbda -Sudan. He works as an English Instructor, Trainer and Freelance Interpreter. He also has been working as a debate leader discussing various topics in many English Institutes, Centers, Academy and schools.

Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker is a poet and writer from Omdurman Umbda -Sudan. He works as an English Instructor, Trainer and Freelance Interpreter. He also has been working as a debate leader discussing various topics in many English Institutes, Centers, Academy and schools.