Progressive poet and lyricist Jan Nisar Akhtar (1914-1976), father of Javed, was one of those who explored love, loss, identity, the lessons emerging from betrayal and eventual healing, and the tormented universe of intimacy

Shafey Kidwai

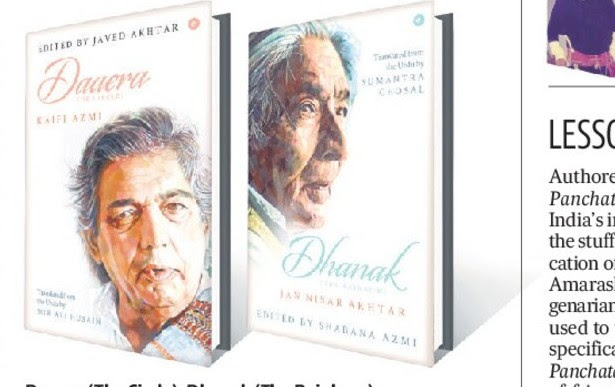

One seldom comes across a husband and wife who have both distinguished themselves in films, literature and activism and share an intellectual and emotional intimacy. Shabana Azmi and Javed Akhtar together form that rare couple, upending the general notion that celebrities are narcissists incapable of amicable personal relationships. Their joint project, a box set of two trilingual anthologies, Dhanak (The Rainbow) by Jan Nisar Akhtar and Daaera (The Circle) by Kaifi Azmi, shows that sometimes celebrity pairings have great creative possibilities.

Urdu poetry often features shattered lovers rejoicing in the sweet, sharp thrill of unrequited love. Progressive poet and lyricist Jan Nisar Akhtar (1914-1976), father of Javed, was one of those who explored love, loss, identity, the lessons emerging from betrayal and eventual healing, and the tormented universe of intimacy. Shabana Azmi’s astute note on the senior Akhtar’s tantalising world reveals that though she is best known for her acting, she also has an acute sense of the poetic. Dhanak, which comprises 26 densely textured poems translated by Sumantra Ghosal, draws on the dilemma of a conscientious person living in a world bent on stifling an individual’s multiple identities. The memory of bygone days is an unceasing motif that is viewed and skewed through every conceivable literary trope, with Akhtar employing subtle similes to conjure mental images:

Thinking of the past brings up your memory in such a way that stirs the heartbeat. It is as if a maiden running fast is tripped by a scarf caught in her feet. – Quatrain

In one of his best-known poems, Bezari (meaning “aversion”, though the translator has strangely chosen “apathy”), Akhtar depicts the intense emotional turmoil of separation:

The stars-cold flowers that upon a shroud do lie, / Ash from burnt corpses seems to make up the sky. / The moon a prophet utterly alone, No followers to attend his sermon. / Let me forget it all, my friend.

For the poet, the marital bond is vested with power and imbues life with a thrilling sense of triumph. About this, Shabana Azmi makes a pertinent point: “There was an abundance of odes to the beloved, but rarely, if ever, did an Urdu poet capture so lovingly every detail of his wife s actions as in, Ghar Aangan. Akhtar saheb is perhaps the only Urdu poet who captured the play banter (nakhras) of marital life from the point of view of the wife.”

The translation of Jan Nisar Akhtar’s poems by Sumantra Ghosal is largely expressive and fluid, if occasionally cumbrous. Beyond the ironies of unrequited love and the quasi-religious quest for salvation, modern Urdu poetry also depicts compelling social and political issues. Indeed, this is the hallmark of Kaifi Azmi (1919-2002), whose work forms the other volume in this box set.

Celebrated poet and lyricist Javed Akhtar presents 25 of his father-in-law’s poems, translated by Mir Ali Hussain, in Daaera(The Circle). Kaifi Azmi came to prominence in the 1940 and ’50s, when a group of progressive poets comprising Josh, Faiz, Ali Sardar Jafri, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri and the like turned away from mysticism and nostalgia and towards the chaos of a world obsessed with faith and politics.

Mapping the creative terrain of Azmi’s sublime poetry, Javed Akhtar asserts that Kaifi holds fast to human dignity even in moments of epiphany: “Very often, poets compromise pride for love and can be seen begging the lover for mercy and generosity. In contrast, in his romantic poetry, Kaifi Saheb accepts the separation from his lover but does not let it diminish his self-respect. Main aahista badhta hi aaya / Yahaan tak ke us sey juda ho gaya main (I kept walking away – slowly / until we became separated). The poet’s dignity is not compromised… and perhaps the dignity adds a grand and dramatic effect to his poetry.”

Hope and despair have often been the subject of poetry, but uncertainty about the future turns on fear. Fears overshadows everything; it breeds faith, smothers the hope for change, and the emancipation of humanity becomes a distant dream. This puts off Kaifi completely: Today, life has another name – Fear / fear is the ground in which / Factions sprout, communalism grows / streams cut away from the sea / as long as fear remains in hearts / All I have to do is to switch faces Change the way I speak / no one can then destroy me / No one can celebrate the festival of humanity” (The Woman With Many Faces).

Lord Ram is highly esteemed in Urdu poetry, and several poets have made him the object of abiding reverence. Kaifi zeroes in on the values that Ram represents. His famous poem, The Second Exile, explains why Ram left the capital again so hurriedly: “Ram had not even washed his feet in the Sarju river yet / when he noticed the deep stains of blood / Getting up from the river’s edge without washing his feet / Ram took leave of his home saying: “The atmosphere of my capital does not agree with me.”

There are occasional traces of turgidity in the translation but don’t let that put you off. All these poems are still relevant. In sum, the volumes in this box set merit several reads.

_____________________

Shafey Kidwai is a professor of mass communication at Aligarh Muslim University

First published in Hindustan Times on April 29, 2023. Received through email