With the receding of connections with the past, and in the absence of collective living, migrant children often did not get much opportunity to speak their language. All that remained of the old Sindh for many was silence and indifference.

Rita Kothari

Meanwhile, the fearful circumstances under which the Sindhi Hindus left, the embarrassment of living in refugee camps and struggles to reestablish themselves made the ‘past’ recede from conscious memory. A tiny section led by Bhai Pratap Dialdas in Adipur, Kutch, attempted to create a region where Sindhis could find cultural continuity and economic opportunities. However, by the time those possibilities could come to fruition, Sindhis were dispersed across different regions and had too many concerns to uproot themselves once again and make Kutch their home. With the receding of connections with the past, and in the absence of collective living, migrant children often did not get much opportunity to speak their language. All that remained of the old Sindh for many was silence and indifference.

Through this period, it was particularly significant that help came to Sindhis from Hindu majoritarian groups, once again consolidating the perception that Congress had let them down. Bhavnani discusses the anti-Congress sentiment, and how that brought about a significant shift in future voting patterns: Sindhis started voting in large numbers for other parties, such as the Jan Sangh, Hindu Mahasabha and Praja Socialist Party. There is continuity with the present, seen in Sindhi support for the Bharatiya Janata Party. In tandem with physical distance from Sindhi Muslims (whom many Sindhi Hindus would remember fondly) and a psychological distance from the past that generated misery and stereotypes, Sindhis also began a systematic de-Islamicisation of their mixed and syncretic legacies. For instance, the practice of visiting pirs (Sufi priests) and dargahs (Sufi shrines), common among Sindhi Hindus, quickly waned after Partition. In places such as Gujarat, where non-vegetarianism is associated with Muslims, the Sindhis began to turn vegetarian.

Although this has been commented on in previous scholarship, Bhavnani also documents Sindhi efforts to transplant religious and educational institutions to the Indian landscape. While she has a grip on the detailed history of educational institutions, Bhavnani does not attempt to see the conceptual difference or link between ‘transplanted’ and ‘redefined’ religion. It may be worth knowing at this point what Bhavnani says about the Partition experience of Sindhi Hindus. Recognizing the difficulty of generalizing, Bhavnani delineates the divergent contexts of class, region, and means of travel, destination and chance, all of which played a role in the Partition experience of Sindhi Hindus. Age was a significant factor in the Partition experience, too: younger refugees were often able to rehabilitate themselves with greater ease than the elderly. While Bhavnani’s overall observations of the Partition experience of Sindhi Hindus adds little to existing scholarship, her illustration of each context through meticulous research is commendable.

Similar detailing characterizes the discussion on Sindhi Hindus who stayed back in what became Pakistan. The story of Hari Dilgir, a well-known Sindhi-language poet, is a moving episode provided by Bhavnani. Dilgir was also a public intellectual and freedom fighter. His determination not to leave the land of his ancestors, which he was finally made to do, and the admiration he evoked among Pakistani Sindhi writers, is a telling example of the psychological violence and exile that Sindhi Hindus underwent.

Similar detailing characterizes the discussion on Sindhi Hindus who stayed back in what became Pakistan. The story of Hari Dilgir, a well-known Sindhi-language poet, is a moving episode provided by Bhavnani. Dilgir was also a public intellectual and freedom fighter. His determination not to leave the land of his ancestors, which he was finally made to do, and the admiration he evoked among Pakistani Sindhi writers, is a telling example of the psychological violence and exile that Sindhi Hindus underwent.

Sindhis remain a trans-border community

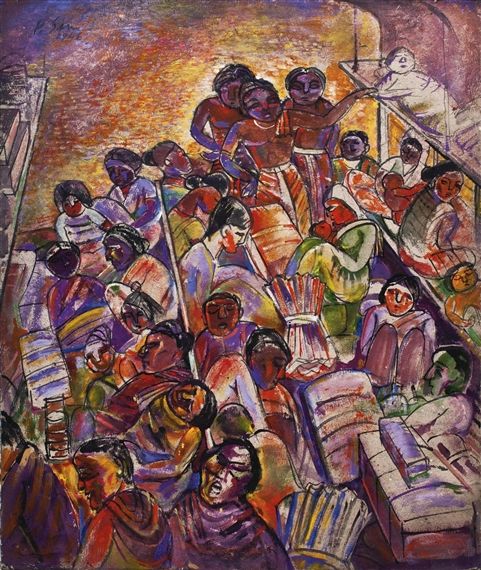

It is to Bhavnani’s credit that at no point does she lose sight of the simultaneity of the Partition experience in India and Pakistan, and Sindhis remain a trans-border community in this historical account. The concluding section takes a panoramic view of Sindhis across India, Pakistan and other parts of the world, constructing and remaking identities across divided histories, rejoining and redefining through social media and conferences. The final section contextualizes the Partition of Sindh in the larger story of the Subcontinent and its divisions in the wake of colonialism. Conceived as a ‘solution’, a way of walling off the ‘other’, Partition generated hopes of land and safety. The irony of havens bringing fresh misery was compounded by the fact that the source of new misery was often not the so-called enemy, but a combination of historical circumstances. Sindhi Hindus remember their indignation at their refugee status with far more pain than imaginary or real interreligious tensions. Bhavnani also foregrounds the role of property – what she calls a “violent lust for land” – as a strong motivation for communal violence against minorities (both in India and Pakistan) as well as against Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs.

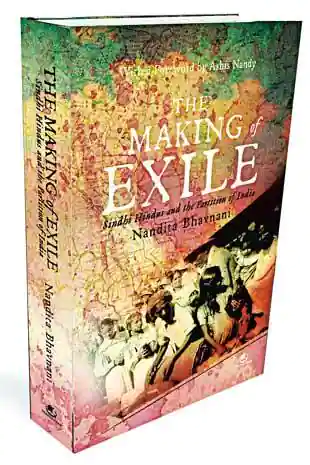

Bhavnani chronicles the story of Sindhi Hindus and their Partition experience across regions and times, providing us with ‘mainstream’ perspectives as well as views from the sidelines. This chronicle is built upon archival work, interviews, memoirs, secondary material and numerous visits to different parts of India and Pakistan. Its breadth and commitment, canvas and detail, macro and micro details are impressively complete. What it lacks – as many books do – is what a reviewer wants the book to be, which is perhaps unattainable. Bhavnani’s attention to the nuances of language – things she hears, words she misses, subtexts that remain undiscussed – and attention to memory and narrative-making tendencies among her respondents is unsatisfactory, if not absent. For instance, the word dyat (a pejorative term used for Muslims by Sindhi Hindus and, at times, even Sindhi Muslims themselves) is used interchangeably with jat, a specific community. Her use of the folk stories ‘Sasui-Punhu Umar-Marui’ – iconic narratives of undying love and Hindu-Muslim relationships – hang as appendages, rather than interwoven into analysis. The relation between the spoken and written word, the juxtaposition of past and present, and how these often get constructed in particular ways, the engendering of testimonies, all these remain unnoticed and untheorised. This makes the reading of The Making of Exile extremely direct and accessible, but it fails to provide a conceptual fiber to a richly detailed history. That maps do not mention a source and an index is missing can only be explained as an oversight. In most other respects, Bhavnani’s study is a benchmark in scholarship on Sindh, and it achieves what it does for being, more than anything else, a labor of love. (Concludes)

Click here to read Part-I, Part-II and Part-III

_______________

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Courtesy: Himal Mag