Partition narratives in different languages and from different regions are replete with references to food. Mixing memory with desire, Partition migrants often remembered sweeter mangoes, and cheaper and more nutritious vegetables in their pre-Partition lives.

Rita Kothari

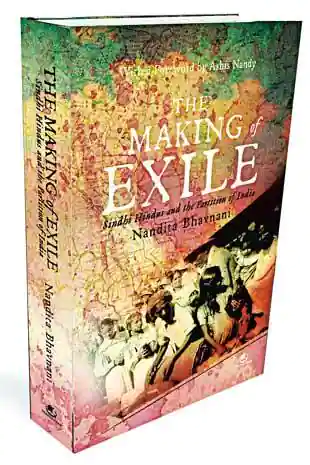

A host of unrelated episodes from the past found a way into my consciousness upon reading Nandita Bhavnani’s The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. For instance, her reference to an increase in dowry practices among Sindhi Hindus after Partition triggered an unpleasant story of greed that I thought I had forgotten. A relative of mine, a Shikarpuri Sindhi, had made a thriving business out of selling electronic and sundry items during her annual trips from Hong Kong to India. Rado watches, vanity boxes with eyeliners and lipsticks, the ubiquitous Charlie perfumes, all would be rolled out of her bags and sold at murderous profit to her poor relations living in not-so-posh parts of Bombay and the refugee camps around. The greed extended to unrealistic demands of dowry from the parents of a middle-class Sindhi girl whom her son married, in the process driving the bride’s family to near-total penury. Bhavnani mentions:

Dowry had long been a social evil among Sindhi Hindus, despite efforts to eradicate it as early as the late 19th century. Now, in India in a context of economic strain, instead of asking for less dowry, families of marriageable boys began to ask for even higher amounts of dowry than before.

If works such as The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama (2008) by Claude Markovits, and Cosmopolitan Connections: The Sindhi Diaspora 1860-2000 (2004) by Mark-Anthony Falzon put into perspective the history of multiple locations in the lives of the Sindhis, Sindhi Diaspora in Manila, Hong Kong and Jakarta (2002) by Anita Raina Thapan illuminated Sindhi Hindu patriarchal practices in the diaspora. Bhavnani’s research hits upon the unfortunate deterioration of the moral fabric after Partition. Thanks to robust and emerging scholarship, it is becoming possible to locate smaller and apparently isolated narratives in the wider context of transnational networks and the changing sociology of the Sindhis after Partition.

If works such as The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama (2008) by Claude Markovits, and Cosmopolitan Connections: The Sindhi Diaspora 1860-2000 (2004) by Mark-Anthony Falzon put into perspective the history of multiple locations in the lives of the Sindhis, Sindhi Diaspora in Manila, Hong Kong and Jakarta (2002) by Anita Raina Thapan illuminated Sindhi Hindu patriarchal practices in the diaspora. Bhavnani’s research hits upon the unfortunate deterioration of the moral fabric after Partition. Thanks to robust and emerging scholarship, it is becoming possible to locate smaller and apparently isolated narratives in the wider context of transnational networks and the changing sociology of the Sindhis after Partition.

Remembrance of things past

Spurred by her desire to pursue research on her own community, Bhavnani’s inquiry began at least 15 years ago. This, therefore, is a highly-anticipated book among those who follow Sindhi scholarship. Battling with silence – so common among Partition communities – like many South Asians, Bhavnani grew up knowing of rather than about Partition. She says:

I cannot remember when I first became aware of Partition. Perhaps I had known from an early age that, as Sindhis, both my parents had been born in another, inaccessible land, where they spent their childhood years. I cannot remember when they first told me about it.

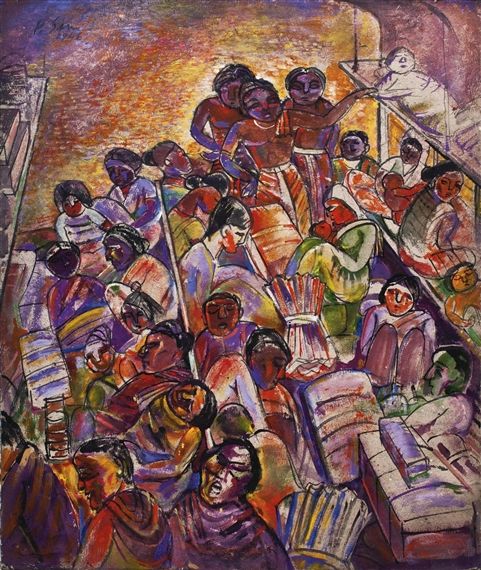

Partition narratives in different languages and from different regions are replete with references to food. Mixing memory with desire, Partition migrants often remembered sweeter mangoes, and cheaper and more nutritious vegetables in their pre-Partition lives. In forms of evocation akin to utopic creations of a never-never land, better and cheaper food is a recurring motif, particularly significant because it constituted the everyday sphere of memory in houses in which Partition was not consciously remembered. Then there were those who underwent the historical experience of Partition, without naming it so. For instance, listening to women who crossed borders during and around 1947, I have often found them recalling fear and anxiety with greater specificity than the names of ships, exact dates or locations; often, the word ‘Partition’ escapes their narration.

Among Sindhis, it was more common to refer to Partition through a long phrase: “jadhain Hindustan-Pakistan thiyo, when Hindustan and Pakistan happened,” which also has the subtextual meaning of “when Hindustan became Pakistan,” implying that a familiar land had become alien. From the more literary and community-conscious Sindhis, words such as ladpalayan (migration/exodus) or virhango (separation) have become more common. Besides the mundaneness and inadequacy of vocabulary, the ineffability of the Partition experience has added to the silence of communities that wished to forget and move on.

Bhavnani quotes Motilal Jotwani: “Can the entire truth about how we lived our lives in the purusharthi camps of Deolali and Kumar Nagar Dhulia be described?” As things stand now, the question may not only be about how to describe, but also with which language (in non-metaphoric terms) to describe. The Sindhi language, the sole identifier of the group, has begun to wane from the lives of urban, second and third-generation Sindhis. Should they or their progeny need to know the past, sources like Bhavnani’s book are where they would have to turn. For Sindhi Hindus who migrated to India during Partition, the trauma lay not only in being wrenched from a homeland, but also from living as stateless and regionless citizens in India. Sindh was not divided like Punjab, but went entirely to Pakistan. Sindhi Hindu refugees had to live with the loss of region, which in the following years had ramifications on language and other forms of historical continuity that territories provide. In the absence of region – and increasingly the waning use of the Sindhi language – a glaring question before the community is what it means to be a Sindhi. The question needs to be addressed, or at least confronted, and this will be returned to later.

The Province of Sindh (now a state in Pakistan) is bordered on the east by the Thar Desert in India, and on the west by the mountains of Balochistan. It contains Karachi and the remains of the Indus Valley civilisation. Tracing its origin to the Indus Valley settlements of Mohenjodaro (a Sindhi word meaning the gate/hillock of the dead), Sindh belonged to various Hindu kingdoms until 712 AD, when Mohammed bin Kasim conquered it and initiated Muslim rule in the region, which lasted undisturbed until 1843. At this point, the British decided that it was strategically important to conquer the region. Colonial land and education policies unsettled the economic and social balance, so that in the 19th century, the Hindu minority – who had been wealthy but unobtrusive – came to dominate powerful positions, evoking the feeling among Sindhi Muslim leaders that they had not got what they deserved. (Continues)

_____________________

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Courtesy: Himal Mag