[From imperial ‘unhappy valley’, to decapitated province, commercial capital, and 21st century megacity, this article reflects on relations of separateness and connectivity between Sindh and its capital city Karachi. These culminated in Pakistan’s post-Independence years, in official and political language, governances of national, provincial and city division, and political rhetoric and violence. The article asks what else might be uncovered about their relationship other than customary alignments and partitions between an alien urban behemoth and a provincial periphery. It develops a topographical view to refer to the physical arrangement of environments but also people’s profane, spiritual and political connections and losses involving place and dwelling]

By Nichola Khan

Breathe (saans) and terrorism

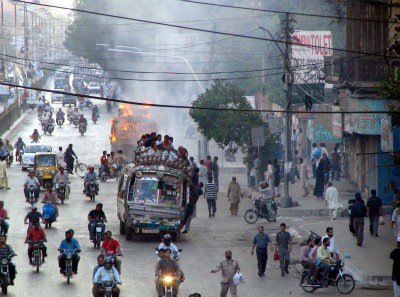

If Karachi and Sindh became familiar through the Sufistic winds of qawwali, breath of zikr, and stench of pollution they became strangers again through the fault-lines that concretize around religious militancy. Themselves born of earlier cross-border wars, these now shape another incursion into Sindh around circulatory flows of politics and capital for terrorism.

In the 1990s particularly, there was support across the city for the religious parties, especially the Barelvi leaning Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (JUP), and to a lesser extent Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and its student wing, the Islami Jamiat-ul-Tuleba (IJT). While older Mohajir generations mostly voted for the JUP, and had been party workers, younger people largely supported the MQM. Now the JUP is a distant memory with little relevance to young people, with MQM becoming so likewise (Khan, 2018).

In these groups, pro-Sufism was not characteristic (Rana, 2010). Nor are Barelvis, a majority in Pakistan, equated with militancy, except a few groups that fought in Kashmir in the 1990s. However, Sufism has more recently recrystallized around sectarianism and extremism, in Deobandi and Barelvi groups who align in their support for the blasphemy laws, and opposition to the state and judiciary (Siddiqa, 2016). While Naqshbandi, Pakistan’s major Sufi cult is mainly comprised of Deobandis, Maulana Masood Azhar, leader of the terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammad, directs his followers to follow Naqshbandi practices (Rana, 2010). Particularly important is zikr, a daily practice involving the repetition of thousands of phrases and breathing and physical exercises, wherein followers renounce their separate existence, temper the influence of the nafs (ego); dunya (wordliness), hawa (vain desires) and shaytan (devil), and attain a concord between terrorism and spirituality.

Current jihadist groups operating in interior Sindh have a precedent in the Afghan jihad of the 80s, the Salafi and Wahhabi militancy of the 1990s, and the 2001–2014 Afghan war. They parallel the rise of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan’s (TTP) social and economic power in Karachi (Rehman, 2017). Many groups train recruits in Interior Sindh, a few hours by rail and road from Karachi. Extremist organizations are increasingly active in Sindh’s central and northern districts. Sectarian militant groups are active in rural areas. Organizations from southern Punjab including Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammad, and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) recruit in Sindh. Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), the LeT’s welfare wing is popular in Sindh’s central and southern districts where, following the 2010 and 2011 floods, it responded more capably than government agencies in providing relief and refugee camps; JuD has since established madrassas across Sindh (Yusuf and Hasan, 2015).

Yusuf and Hasan (2015) highlight increasing militancy, violent extremism, crime, tribal warfare, and violent nationalist and separatist groups in Sindh. While the TTP, al-Qaeda, and other Islamist groups have a limited presence, the sectarian Ahl-e-Sunnat Wal Jammat (ASWJ) and its militant wing, the LeJ, are influential in northern districts. Criminal gangs in Shikarpur, Sukkur, Larkana, Nawabshah, and Hyderabad conduct kidnapping, extortion, armed robberies, smuggling, and provide sanctuary to other criminals, fuelling concerns they could protect TTP militants (12). A kidnapping-for-ransom economy operates wherein the gangs trade kidnap victims, the ransom increasing per sale, then sell them onto gangs in Balochistan or Taliban groups in FATA. Hindus are vulnerable, having significant investments in cotton and agro-business (12). The Sunni ASWJ and LeJ have taken advantage of tribal, political, and sectarian rivalries to offer their support (13). When the TTP’s Mohmand chapter, influential in Karachi, and the Punjabi Taliban claimed responsibility for the 2014 attack on Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport, investigations revealed Sindh’s central districts were key for logistical planning (8). Recruits from northern Sindh travel to North Waziristan Agency to join the TTP (9). Sindh is arguably at a tipping point, lest violent extremist and sectarian groups based in southern Punjab further infiltrate Sindh, and undermine stability in Karachi (Yusuf and Hasan, 2015; Rehman, 2018).

Yusuf and Hasan (2015) highlight increasing militancy, violent extremism, crime, tribal warfare, and violent nationalist and separatist groups in Sindh. While the TTP, al-Qaeda, and other Islamist groups have a limited presence, the sectarian Ahl-e-Sunnat Wal Jammat (ASWJ) and its militant wing, the LeJ, are influential in northern districts. Criminal gangs in Shikarpur, Sukkur, Larkana, Nawabshah, and Hyderabad conduct kidnapping, extortion, armed robberies, smuggling, and provide sanctuary to other criminals, fuelling concerns they could protect TTP militants (12). A kidnapping-for-ransom economy operates wherein the gangs trade kidnap victims, the ransom increasing per sale, then sell them onto gangs in Balochistan or Taliban groups in FATA. Hindus are vulnerable, having significant investments in cotton and agro-business (12). The Sunni ASWJ and LeJ have taken advantage of tribal, political, and sectarian rivalries to offer their support (13). When the TTP’s Mohmand chapter, influential in Karachi, and the Punjabi Taliban claimed responsibility for the 2014 attack on Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport, investigations revealed Sindh’s central districts were key for logistical planning (8). Recruits from northern Sindh travel to North Waziristan Agency to join the TTP (9). Sindh is arguably at a tipping point, lest violent extremist and sectarian groups based in southern Punjab further infiltrate Sindh, and undermine stability in Karachi (Yusuf and Hasan, 2015; Rehman, 2018).

Through mercantilism and extremism, Sufism’s principles of selflessness are cross-cutting religious orientations, enabling complex patterning of unification, division, rendering the familiar strange and vice versa. These circulations are reconstituting Sindh-in-Karachi through a confluence of networks in finance, human trade, abduction, and terror. Repeated attempts at living are inscribed onto the landscape, bodies are enabled to incorporate the spirit of unifying or fatal knowledge, and breath is charged as the bearer of anguish or balm.

‘May you forget the trade you learnt, but yesterday I met you here, today I see you disappear, sailing on ocean waves!’ – Shah Latif, Shah Jo Risalo, Samudi-XIII (Mariners).

Conclusion

The topography of human, material, and environmental ontologies serves to disrupt some imposed and imagined divides between Karachi and Sindh. Displacing heterologies of colonial, national, and Karachi-centric reason, this article problematized the interplay of connectivity and separation in order to destabilise some over-determined divisions between capital and periphery, and open an interstitial terrain for new forays of critical disruption to Sindh–Karachi relations. It questioned some cartographic divisions and logics of post-colonialism and empire that organize relations of strangeness and familiarity in Karachi’s separation from Sindh; divisions between Sufism, terrorism, and Islamic state-nationalism; and ‘Pakistan’ as an imagined Muslim power in South Asia. It prioritized shared, syncretic realities linked to local, national, regional and planetary processes that are distinctly shaped by imaginings of insuperable human and area difference, and Pakistan’s histories of post-colonialism and colonialism.

The colonial approach to religion as an essentialist category underpinning Partition visibly continued in the institution of land into postcolonial contestations over rights and belonging (Jones, 2014). This bears on ways urbanization, climate change, and related migrations are being re-routed through imperial imaginaries of classed and racialized partitions, creating new environments, planetary subjects, and hierarchies (Sidaway et al., 2014). It also brings comparative urban analytic value (Myers, 2014) to Hage’s (2016) contention that the old sentiment of ‘being surrounded by barbarians’ has re-emerged in the global crisis of borders regulating the neo-colonial exploitation of land, resources, and labor; the crisis of ecological borders of domestication that define the modern exploitation of nature; and the civilized world’s ability to control the movements of refugees.

Additionally, the article asked if creating alternative ways of relating to and inhabiting the earth might redirect passions toward new, shared visions that are instantiated in the tracks, tidemarks, volumes, seepages, and temporal flows of their own movement. Discourses about moving forward, moving backward, vacillating, being stuck, and going nowhere regarding Karachi’s crises of land, borders, climate, and migration posit mobility as a political text. They enrich the motile elements of topography. Motile thinking has contributed much to decouple theoretical sequelae from ontological ones, people from the categories that confine them, and to engage an ‘ontological reversal’: wherein motion is seen as primordial and stable entities the derivative outcomes of the raw material of motion (Holbraad, 2012). While it may be wholly correct to argue that maps for life deaden new possibilities for living, the article argued we should not miss opportunities for relating to the silent suffering of the disaffected, and to lives experienced as immobilized by their losses, or an inability to transcend their confines. The task is to slow down, not just in relation to capitalism, but enough to acknowledge encounters of feeling, and to disrupt customary barriers to mutual recognition.

The failures of the British and Pakistani authorities, to clear Karachi’s urban mountains of accumulated rubbish gave way to chronic traffic and waste problems, air pollution, water shortages, prolonged power cuts, unmitigated heat and the reckless destruction of heritage. These co-occurred with the erection of crudely designed super-highways, mega-transport systems, and gated communities that displaced Karachi’s unwanted communities to the peripheries of its world-class vision. Notwithstanding, Burton’s (1851) elusive imperial dream of avenues of abored shade was resurrected in 2008 by city mayor Mustafa Kamal who instituted plans for a ‘Green City’ that could combat air pollution. Around 2.2 million conocarpus plants, terrestrial mangroves native to the Americas and West Africa were planted. Rather than indigenous local trees such as neem, ficus, lignum, eucalyptus, or imlee, the cheaper resilient conocarpus now borders Karachi’s major arterial roads. Related fears arose around the perceived colonization of Karachi by an alien species causing breathing problems, asthma, and effacing ecological diversity (Mujahid, 2018). If this story represents the return of an anxiety symptom around desires to enforce borders of soil and belonging that outsiders cannot have, it also represents a resignification of the threat of foreign takeover and the toxicity of city-politics for the environmental context.

In the urban prison the air is putrid, filtered, poisonous, an intense indicator of despair, and a ‘paradox’ of planetary urban development and progress (Brenner and Schmid, 2015). In imperial times, links were made between foul air and deadly diseases, and between putridity, crime, and moral dissolution. Imperial air was also murderous, as with prisoners asphyxiated in the Black Hole of Calcutta: not unlike illegal migrants who suffocate in trucks en route from Pakistan to Europe. In air, ventilation, and the struggle to control one’s breathing, imperial, colonial, and neoliberal rationalities interact.

In the urban prison the air is putrid, filtered, poisonous, an intense indicator of despair, and a ‘paradox’ of planetary urban development and progress (Brenner and Schmid, 2015). In imperial times, links were made between foul air and deadly diseases, and between putridity, crime, and moral dissolution. Imperial air was also murderous, as with prisoners asphyxiated in the Black Hole of Calcutta: not unlike illegal migrants who suffocate in trucks en route from Pakistan to Europe. In air, ventilation, and the struggle to control one’s breathing, imperial, colonial, and neoliberal rationalities interact.

Arguably the real post-Independence crisis was not the influx of refugees, but Karachi’s divorce from Sindh, approved in the Sindh Assembly. Similar betrayals continue in the dispossession of lands and subsistence livelihoods by Waderas and developers who collude around profitable real-estate developments.

These developments, occurring across the Global South, are obliterating working and poor populations through forcible evictions, and reminders of disposability. I argue they also hold possibilities for reconstituting city life and politics in the unoccupied ‘oceanic’ (Freud) spaces that nestle besides the dominant dividing lines between things.

Meanwhile, Karachi continues to swallow the hinterland, like the Indus, with its temporal and temperamental fluvial currents, flows, and enraged flooding. When through massive losses of home and certainty in the ground beneath occur through forced dislocations, flooding, drought and desertification, the self and its boundaries are lost, given to unfamiliar, random dispersals across city environs. Thinking topographically is not about repairing physical, political or imagined walls of hostile familiarity. It means re-stitching a connectivity dependent not on origin, but on new ways people can realign their shared comings and goings.

It also comprises an ethical endeavor to recover epistemological forms of effacement, and to embed deep perceptions of life into thinking about Karachi. When body and spirit are subjected to extreme losses of mooring and direction, the usual politics of sustained antagonisms is disoriented too. What emerges instead of rights and ethnic determinations is an excess of city and rural life synthesized into strange propinquities of earth, breath, air, land, and water. In these overcrowded spaces where citizens are forced into alien familiarities, life can arguably renew in a merging of people who must keep living, and striving, together. (Concludes)

__________________

About the Author

Nichola Khan is a Reader in Anthropology and Psychology, and Director of the Centre for Research in Spatial, Environmental and Cultural Politics at the University of Brighton. She is author of the following books: Mohajir Militancy in Pakistan (2010, Routledge), Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi (ed., 2017 Hurst & Co.,) Mental Disorder: Anthropological Insights (2017, University of Toronto Press) and Arc of the Journeyman: Afghan Migrants in England (in press, University of Minnesota Press). She is currently developing a literary anthropological project on war and migration in twentieth-century Chinese South-East Asia.

Click here for Part-I , Part-II , Part-III, Part-IV , Part-V