Sindhi horse is the least described, despite carrying a rich history behind it and a huge significance in shaping the socio-cultural characteristics of Sindh and Kutch

BY BIKRAMADITTYA

This year’s (2015) monsoon was a bit too much for Gujarat, and parts of the Acacia dotted sandy landscape of Banni in Kutch, now resemble lakes with vegetation jutting out like little green islands. As our truck moves along the Bhirandiara-Dhordho route, the familiar sandy expanse is back, and so are the grazing cattle – the bighorn Kankrej cows and the Banni buffalos with their donut horns.

Suddenly, across the irregular rows of Mesquite scrubs, my eyes catch a glimpse of a few animals – not buffalos or cows, not even the run of the mill sheep herds, but a pack of horses. Half a dozen of them, including small foals, they browse on the thorny scrubs. I ask Rasool, the owner and driver of the pickup truck we are in, to stop, as we jump down, cross the road and stealthily approach the pack. The horses prick their ears sensing our approach, allow us till a certain distance and then take off like wild winds. Their backs glistening in the desert sun, untrimmed manes waving like the sedgebrush in the meadows, they run away from us, their hooves beating like drums on the dirt tracks from where tiny whirlwinds rise towards the sky.

This is the Wild West of India, and these Mustang-like beasts are the Sindhi horses. “This is gonna be exciting!” I tell myself. I am on my second visit to Banni grasslands, this time to know more about the Sindhi horses. And watching them run wild across the desert definitely signifies a great beginning.

My friend Ovee Thorat is a scientist working at the RAMBLE field station in Hodka, a small village in Banni area of the Rann of Kutch and it was on her invite I visited this region last winter. Back then, she had taken me to meet Haji Jafar, a well-known horse enthusiast and breeder of this region. That was my first tryst with the Sindhi horses, igniting a quest to learn more about these desert steeds.

It was in Jafar’s backyard, I first got to know about the distinctiveness of the breed and the constant but uncharted effort that Jafar and his likes were investing in to keep the breed alive. Under the shades of the Babool trees in the yard, we had found seven horses – grownups and yearlings among them. A few others roamed about at a distance, grazing on the desert scrubs. Jafar talked about each horse as he showed them – pointing out the differences between the Kathiawaris and the Sindhis, about their physical traits and about their spirits and characters.

Kamboja warriors, who played an important part of the cavalry during the Mahabharata war, settled in present day Sindh and Punjab.

Of all these breeds, the Sindhi is the least described, in spite of carrying a rich history behind it and a huge significance in shaping the socio-cultural characteristics of Sindh and Kutch, not much is known about this breed.

A three month long hunt and then connecting the dots gives me a sketchy idea of what might have happened through the ages. Dr. Parkash Singh Jammu, ex-professor – Sociology and Social Anthropology, Punjabi University, Patiala, talks about the Kamboja tribe, who were pushed from Tajikistan area by the Mongols around 4000 B.C. These people, settled in the regions of present day Afghanistan, were expert horse riders and breeders, who continued their trade of horses with Europe through the Silk Route. Another researcher, Deepak Kamboj, writes “Throughout the Indian literature, the Kambojas are honored for their horses. All major Indian religions have a lot to say about them. Jain Canon Uttaradhyana-Sutra informs us that a trained Kamboja horse exceeded all other horses in speed and no noise could ever frighten it. The epics, Puranas and numerous other ancient Sanskrit texts all agree that the horses of the Kamboja, Bahlika and Sindhu regions were the finest breed.”

What I gather from Dr. Jammu’s and Deepak Kamboj’s documents (www.kambojsociety.com) and from the writings of noted Sindhi historian Muhammad Hussain Panhwar, can be summarized as:

The Sanskrit description for Kamboj people is Ashvaka, meaning horse people or riders. Many historians like Christian Lassen, Saan Martin, L. Bishop, Dr. J. C. Vidyalnar, Dr M. R. Singh, William Smith, N. L. Dey, William Crooke and Kirpal Singh are of the opinion that the word Afghan has been derived from Ashvakan. J. W. McCrindle in ‘Megasthenes and Arrian’and ‘Alexander’s Invasion of India’, observes, “The name Afghan has evidently been derived from Asvakan, the Assakenoi of Arrian.”

Kamboja warriors played an important part of the cavalry during the Mahabharata war, both on the Kaurava’s and the Pandava’s sides. At the end of the war, the Kamboja warriors of the Kaurava side were taken as slaves by Krishna to Gujarat. These people were freed after thirty six years and settled in the kingdom. The Kambojas from the Pandava’s side however went ahead to settle in present day Sindh and Punjab.

Kamboja people have been mentioned time and again in literatures like Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, Patanjali’s treatise, Kalika Purana, Buddhist Jataka text, Arthashashtra of Chanakya, and Abu L Fazal’s Aina-i-Akbari.

Kamboja people and their horses can be traced to two regions; one of them the Kambu mountains in Sindh, facing Lakhi Hills across Baran valley, half way between Hyderabad and Karachi and the other being Kutch

Kamboja cavalry fought in various battles; as supporters of Haihaya Yadavas against Ikshaku ruler Bahu (Puranas), as allies of Magadha king Jarasandha against Krishna (Bhagwat Purana), as mercenaries for both sides in the Kurukshetra war (Mahabharata), as supporters of sage Vashishtha against king Vishwamitra (Ramayana), with the Persians against the Greeks (Herodotus, IV.65-66), in the army of Chandragupta Maurya (Mudra Rakshasa) and Brihadratha Maurya (Kalika Purana), as a part of the Pala army of Bengal (Mungher Inscriptions B.8, V.13), and as cavalry for the Gurjara-Pratihara rulers (Dr H. C. Ray, Dr R. C. Majumdar). The Aina-i-Akbari by Abul Fazl Alami mentions the 9000 strong Kamboja cavalry of General Shahbaz Khan that Akbar used for various conquests.

Kamboja people and their horses can be traced to two regions; one of them the Kambu mountains in Sindh, facing Lakhi Hills across Baran valley, half way between Hyderabad and Karachi and the other being Kutch (Kamboja > Kavoch > Kaoch > Koch > Kutch).

So, horse breeding and trading across the Middle East to India continued through the Mughal era. ‘Riding Through Change – History, Horses, and the Restructuring of Tradition in Rajasthan’, Elizabeth Thelen’s thesis for University of Washington, Seattle, mentions “Perhaps through its connections with (Mughal) court nobles, the horse became a symbol of nobility and fine manners. An encyclopedia of the horse, the Farasnama, was developed that drew from both the Indian tradition of Shalihotra, illustrated manuscripts detailing the care of the horse, as well as Persian Furusiyya literature, which is a collection of horse lore.”

However, the British stressed upon imported breeds for both their civilian and cavalry requirements and the Indian breeds were deliberately pushed towards extinction. Jos J. L. Gommans, in ‘The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire c. 1710-1780’, points out “Toward the end of the eighteenth century the horse trade began to decline in India because of pressures from the British East India Company (EIC), which settled in Bengal in 1757. Trade became more difficult in EIC controlled areas as the EIC attempted to control the movements of the horse traders and the EIC settlements blocked some routes.”

Nidhi Sharma, in ‘Transition from Feudalism to Democracy: A Study of the Integration of Princely States of Rajasthan (1947-50 AD)’, writes “Under the British paramountcy, local breeding of horses and the horse trade continued to decline. The imperial service troops were equipped in the British style so local breeds became less viable in cavalry units. The agreements often stipulated the type of horses. For instance, the Jodhpur Lancers were to be mounted on Arab, Valer (Australian thoroughbred) or English thoroughbred horses.”

John Lockwood Kipling, in his book ‘Beast and Man in India: A Popular Sketch of Indian Animals in their Relations with the People’ (1904), shares his British scorn for the Indian breeds, “The animals most liked are the stallions of Marwar or Kathiawar. White horses with pink points, piebalds, and leopard spotted beasts are much admired, especially when they have pink Roman noses and lightly-colored eyes with an uncanny expression. Their crippled, highly arched necks, curby hocks, rocking gait, and paralytic prancing often proclaim them as triumphs of training.”

His son, the famous author Rudyard Kipling, in his epic novel Kim portrays Mahbub Ali, a Pashtun (Afghan) horse trader as the main ally of the protagonist Kimbal O’Hara (Kim). Throughout the novel, Rudyard uses different proverbs and statements that have some horse connection. The novel also talks about the Kathiawar (Kathiawari), Kabuli, and Balkh horses other than the Arab and the Polo Pony. But the breed Sindhi is mentioned nowhere.

Perhaps their fervor to exterminate the prominent native breeds were focused on the elegant looking Marwari (of Rajput pride) and Kathiawari (of the Gujarat royals) that the plain and endurant Sindhi, the horse of the nomads, got little attention. It therefore remained, free-ranging in the deserts of Kutch and the hills of Sindh, helping the Maldhari cattle-grazers move camp from one pasture to the other.

A good quality Sindhi can go up to 40 km per hour in Rewal (Amble)

Back in Ahmedabad, this July, I remember speaking to Anish Gajjar, equestrian Trainer, riding instructor, and founder member of Equestrian Club of Gujarat. As we sat across the table in a cafe on that rainy evening, the enthusiasm in his voice as he spoke about the Sindhis was not to be missed. “There is a lot of diversity in this breed, and I favor this breed. They are very good for long rides. A good quality Sindhi can go up to 40 km per hour in Rewal (Amble). But the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) and the Equestrian Federation of India (EFI) are yet to see this breed participate. I believe, properly trained Sindhis will do great in events like pole bending, obstacle racing, barrel racing, and endurance riding.”

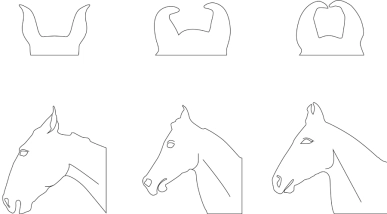

“What about the breed standards?” I ask. “There are no strict standards in place, or no list to conform to. A Sindhi you find in Kutch area will be different from one you find in Surat – these two being the main centers of breeding. In most places, the breed has got diluted in order to mate the stallion or mare with the nearest counterpart available. I have even found that an offspring from a Marwari stallion and a Marwari mare being labelled as Sindhi just because it had straight ears, instead of the curved ones. However, generally speaking, the domed forehead, straight ears with an inward curve at the tip (tulip ears), larger distance between the base of ears (compared to the other two breeds), an almost straight back, a sloping croupe (hips), and a low set tail are the characteristics of a Sindhi.”

This time, I head to Dumado, Haji Jafar’s village, a little more informed than last time. Knowledge that would help me look at these horses with a different eye. As we enter Jafar’s yard, he welcomes us with a smile of recognition. Jafar now has ten horses – mostly Sindhi. We talk about training –people familiar with the British style of horse training will certainly find a difference here. The training for horses here starts at the age of 24 months. The horse is first bridled (the reins put in) and taught to endure the bit in its mouth for a few days, a few hours each day. Once it is accustomed to the bridle, the Pachri (horse cloth) is put on its back and kept on for 2 to 3 hours for a few days. Then comes the time for putting up the saddle and the girth. After this, a young boy mounts the horse while an experienced rider uses a neck rope to lunge the horse in large circles. The bridle is kept on, and tugs on the rein coupled with the pull of the rope are used to associate the horse with the desired movements. About 8 to 10 days later the control is transferred to the bridle. After a month of riding, the horse is taught the famous Rewal Chaal or lateral ambling gait. Sindhis, like Kathiawaris and Marwaris are said to have a genetic trait for Rewal and a horse usually learns this in a month. Once the horse picks up this favored gait, which allows it to run long distances without tiring itself or the rider, it is trained for the Rewal races. Each year, from October till February, about 15 to 20 races are held in the neighboring areas with the winning prizes ranging from Rs.25000 to 50000.

Our conversation is interrupted as another horse owner brings in a mare for mating with one of Jafar’s stallions. Jafar instructs his brother to bring out the stud and both the horses are led towards the faraway scrubs, a young foal trotting behind the mare. Meanwhile, another family member brings out a young stallion for training, one of last year’s yearlings I recognize.

From Dumado we now travel 12 kilometers ahead to Dhordho, famous for its white Rann. Here, Ovee has setup an appointment with Abdul Kalam Morana, another prominent horse breeder of the area. Morana’s house is within a high-walled compound, much in contrast with Jafar’s open yarded pastoral house, though both of them belong to the Maldhari community of cattle-grazing nomads. We meet Abdul Kalam Morana and his nephew Abdul Jalil, the horse trainer, in the sitting room that has its walls daintily decorated with traditional Kutchy mudwork. After the introductions I ask Morana about his horses. “I have four horses – a stallion of three years, an eight year old mare and her two fillies; one of 16 months and one of 3 months,” he proudly declares.

I want to know about the training. The sixty year old speaks, “Formal training starts at 24 months, but actual training starts from the time a foal is born. The handler touches the foal and caresses it so that it starts becoming familiar. It doesn’t object to the person’s presence near it or hides behind its mother anymore. At four months, we put the foal on halter and teach it to follow the handler. During this time it is also taught to rear up or to lift its legs on cue. At 18 to 20 months we put the horsecloth, saddle and girth and also the bridle. It is then led for walks up to half kilometer.”

“And do you put some weight on the horse after this?” I enquire. He says, “No, we don’t put dead weight like sacks of rice on the horse. A horse should be trained to carry a rider, a living being who can shift and adjust, not a dead weight that sags. It’s not a donkey!”

“At 24 months, the horse is bridle trained to move forward and backward. After this, the rider mounts the horse.” Morana continues. “After it gets used to the rider and doesn’t try to dislodge him anymore, it is taught the movements – Choubaz (trot), Mandri (canter) and Velar (gallop). The Varra or Rewal is not a movement, it’s a gait and the rider has to get this out of the horse. It takes about two months for the horse to learn and get the Rewal ingrained in it.”

After this brief chat, we are invited to take a look at the horses, and while we walk towards the stable, Morana talks about the Sindhi breed and its significance to his tribe. “We are Maldhari people, cattle-grazers. From time immemorial we have been roaming about in search of new pastures for our cows and buffalos. The Sindhi horse is indispensable for us. Even in these days, when you see us settled in houses and owning pickup trucks, we depend on the Sindhi when we have to go searching for a lost herd in the grasslands. A Sindhi can tolerate high and low temperature extremes of Kutch and can survive without special fodders. It grazes on the grasses and sedges on its own. It can cover a distance of 65 kilometers, with a rider, alternating between slow and fast paces, in three to four hours.”

Abdul Jalil opens the stable door. It’s more like a corral with a covered shed at one end. A huge mare is seen munching on its fodder while the two fillies Harini (16 months) and Gudala (3 months) prance around. Gudala is curious; she rushes to check us out. Harini earns a stroke from Jalil. Later both of them go and snuggle around Morana. He carries on talking about his passion, “I have been riding since I was a six year old and training horses since I was around 11. These days, my nephew Jalil trains them. I only do test rides to check if the training is perfect and pass my feedback to him if any corrections are needed.”

Though Morana talks about Sindhi horses being left open to the elements and surviving on desert vegetation, his horses are well-fed and sheltered unlike Jafar’s free spirits. Morana is serious; the stud he uses for breeding comes from a person in Navsari, a town 800 kilometers away.

We take leave from Morana and head towards a Maldhari settlement – a place where Rasool and his clan have put up a temporary camp after their village was washed away in this year’s heavy downpour. Rasool laments about the cattle and horses that were killed by the calamity as he drives us towards Hodka. Once again I ask him to stop the truck as I discover another pack of Sindhis cantering through the landscape, snorting and shaking their heads now and then sending faint clouds of dust flying out from their manes. The desert sun keeps glistening on the backs of the Sindhi horses. Mustangs of Kutch!

___________________

Courtesy: Gujju Blog (Posted on October 13, 2015)

[…] Read: Sindhi Horses – Mustangs of India’s Wild West […]