India’s nomadic pastoralists migrate for eight months a year, covering huge distances

Kate Eshelby

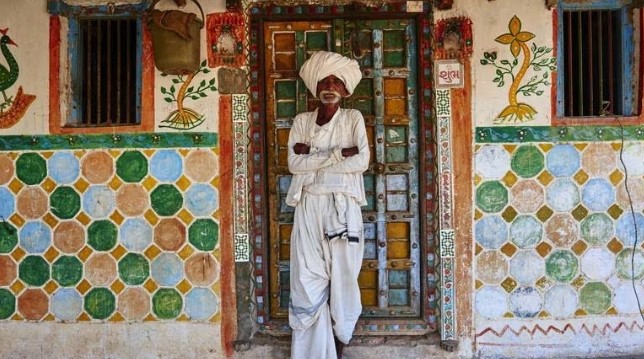

The animals are returning on a biblical scale, flooding into this green expanse, like grains of sand rushing into an hourglass. Water buffalo, camel caravans, herds of cows and goats swarm over the horizon towards me on these vast, stark plains known as the Banni grasslands; each group framing a white beacon, the Rabari herders who lead them. The Rabari stride among their throngs dressed in white frilly shirts, turbans and sarongs tied up to create baggy trousers.

I’m travelling through Kutch, a desert region which sits like an island within Gujarat, one of India’s less-trumpeted states, yet skirts the much-visited Rajasthan. Kutch is the heartland of the Rabari, nomadic pastoralists who still migrate across India for eight months a year, covering huge distances, with their animals, looking for grazing and carrying their possessions: beds, pots, all piled high on top of their camels.

Kutch is an ancient land across which the Rabari have crisscrossed for more than a thousand years; they originally came, it’s thought, from the Iranian Plateau. This weathered land is home to India’s oldest civilization, the Indus Valley and there are still remains, like the ruins of Dholavira, one of the grandest cities from this time, which rises out of a remote pocket of Kutch’s desert. However, it’s the Rabari who I’ve come to see, in particular the Dhebaria, a subset, who still maintain traditional lives.

Kutch is an ancient land across which the Rabari have crisscrossed for more than a thousand years; they originally came, it’s thought, from the Iranian Plateau. This weathered land is home to India’s oldest civilization, the Indus Valley and there are still remains, like the ruins of Dholavira, one of the grandest cities from this time, which rises out of a remote pocket of Kutch’s desert. However, it’s the Rabari who I’ve come to see, in particular the Dhebaria, a subset, who still maintain traditional lives.

Also read: The Desert Frontier: A History of Travel and Nomadism

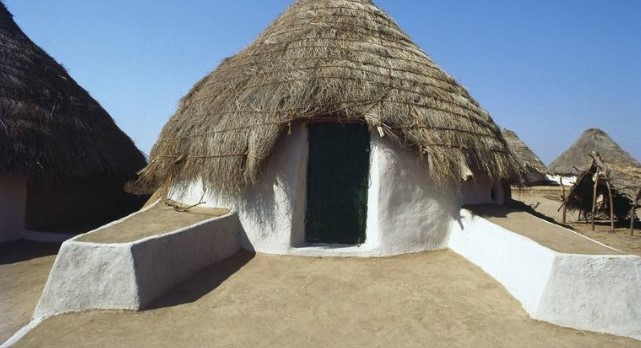

The Rabari are swooping in like arrows to the fires being lit outside their homes. For only a few days they’ll sleep under a stretch of cream tents – before they’re off again. The tents are simple canvas covers held up by wooden poles; yet part of the elaborate world which the Rabari encircle themselves with. The poles, incised with beautiful floral designs, lift the shelters above intricately carved wooden beds, which a rainbow of pom-poms hang from and are covered in hand-embroidered quilts. Decorative camel saddles lie on the ground; and even the water containers have brightly colored hand-stitched covers.

A woman beckons me over to her tent; her eyes twinkle an iridescent blue green. She sits boiling chai over a fire and hands me a cup. Rabari women, dressed in black, contrast with the men, but their woolen shawls are edged with a tease of color and their brocaded blouses sparkle.

Rabaris know that they’re striking to look at and their way of life is fascinating to outsiders. Yet they don’t often welcome visitors. I’m lucky to spend time with this group thanks to my guide, Kuldip Gadhvi.

Rabaris know that they’re striking to look at and their way of life is fascinating to outsiders. Yet they don’t often welcome visitors. I’m lucky to spend time with this group thanks to my guide, Kuldip Gadhvi.

His story is born, however, from tragedy. In 2001 his life changed when a devastating magnitude 7.7 earthquake destroyed his home in Bhuj, the capital of Kutch and the place I begin my trip. It’s a palace-filled city with kaleidoscopic bazaars selling textiles and a hilltop fort.

Also read: Like here, like there

“20,000 people died, but luckily my mother and brother survived,” Kuldip tells me. “Although we lost all our possessions and had to live in shelter for three years.” Afterwards he had the chance to visit the UK and it was during this time that he fully appreciated the vibrant culture surrounding him back home.

He returned to set up his company Kutch Adventures India, going on to win a prestigious gold Responsible Tourism Award in 2014. “My life started after the earthquake,” he continues. “I now know that nothing is forever.” This experience has certainly shaped his attitude and friendly, happy-go-lucky nature.

It quickly becomes obvious that Kuldip has built up trust among the Rabari; for starters he’s adamant that no photographs can be taken of them. His visits have as little effect on them as possible.

It quickly becomes obvious that Kuldip has built up trust among the Rabari; for starters he’s adamant that no photographs can be taken of them. His visits have as little effect on them as possible.

The Rabari’s way of life is already riding plates of change, particularly since the earthquake. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister is Gujarati so keen to develop his home state, although sadly the environment and those who rely on it don’t feature on his list of priorities. Despite Kutch having no industry before the earthquake, the Government wanted to revive the region after the disaster so gave tax breaks to any companies who moved here.

Factories producing anything from pipes, cars, switches and tiles jumped in; coal-fired power plants now gush black smoke. Yet the Rabari have adapted to the changes on their land; I see them leading their boundless camel caravans along India’s highways. Away from the roads Kutch remains wild with swathes of desert and grasslands, edged by the Arabian Sea to the south and a huge salt desert – one of the world’s biggest – shimmering white to the north.

Embroidery industry

The Rabari have always had their own industry; they produce some of the world’s best embroidery, each sub-group having its own distinct motifs. Although as Kuldip says, “it’s more art than industry, used as an expression of their culture.” Traditionally women created them as part of their dowries. But this was banned in 1995 because the amount of embroidery needed for dowries was escalating. Male elders blamed this for the time needed before brides were moving into their in-laws’ homes.

Rabari women still embroider some of the most magnificent folk embroideries but only now for commercial work. For their personal use they have new styles, with an embellished use of ribbons and trims.

It’s not just the Rabari who embroider; this region is known for its handicrafts, with other communities also weaving, dyeing and printing some of India’s finest textiles. Kuldip takes me to visit several of these cottage industries, many of which continue to use natural dyes. First stop is Bhujodi, a village just outside Bhuj, full of hand-woven shawls, scarves and blankets in bright pinks, greens and purples.

Also read: Geeta Rabari – The Koyal of Kutch

Nearby we watch hand-block printing, then wander among the results: hundreds of different patterned pieces of material lying drying in the sun. We drink chai in another village, Kukma with national award-winning rug weaver Tejsibhai who weaves traditional rugs on nomadic looms using camel, sheep and goat wool. I buy a stunning one at the bargain price of $60.

The following day we go further north to the village of Hodka, it’s like walking into a rainbow and home to the Meghwal, another tribal group known for their embroidery. They make appliqué quilts sitting outside on the porches of their brightly coloured mud huts known as bhungas (the inside walls wink with ornate mirror work). Long full skirts and veils flare out in a clash of colours as the women move, and thick bracelets ride up their arms.

They live close to the Banni grasslands which are crisscrossed by many different herdsmen, not just the Rabari, so we stop and spend a few days here, visiting the various nomadic groups: Mutwa, Bharwards, Charans, Ahir and Jats. I become particularly intrigued by the Jat buffalo herders. Originally from Pakistan, which borders Kutch to the northwest, they are Islamic and even more closed to outsiders than the Rabari (although again they welcome Kuldip). The women wear nose rings so big they have to use ties from their hair to hold them up.

They live close to the Banni grasslands which are crisscrossed by many different herdsmen, not just the Rabari, so we stop and spend a few days here, visiting the various nomadic groups: Mutwa, Bharwards, Charans, Ahir and Jats. I become particularly intrigued by the Jat buffalo herders. Originally from Pakistan, which borders Kutch to the northwest, they are Islamic and even more closed to outsiders than the Rabari (although again they welcome Kuldip). The women wear nose rings so big they have to use ties from their hair to hold them up.

Mass weddings

I’ve planned my visit in Kutch to be the end of the monsoon because it’s the only time in a year when most Rabari come back to their villages. Many have mass weddings during this period, often on Janmashtami, a festival celebrating the Hindu God Krishna’s birthday. “Many herders worship Krishna as he was also a cow herder,” Kuldip explains. “It’s when everyone can get together as usually they are out wandering with their animals.”

We’re invited to Kukadsar, a Rabari village close to the Gulf of Kutch, where they are having seven weddings that day. Arriving just as preparations are under way, the brides soon appear, each covered from head to foot, hiding their faces and tied to their future husbands who wear sparkling crowns.

Also read: Communities of Kutch, Gujarat

The couples are led through the village to the temple, passing under torans (sacred hangings) to keep evil eye away and surrounded by crowds singing. They circle around fires as Brahmins chant and drums play loudly. A frenzy of red follows as kumkum powder is thrown on the men’s white clothes, before we all sit down to a Rabari feast of daal, rice, homemade chutneys and koprapak (a delicious coconut and milk pudding).

The festivities go on late into the night; then the following morning I wander out towards the edge of the village. A group of Rabari are already preparing to leave. Clothes are drying on thorn bushes; their beds lie scattered. Now the monsoon is over it’s time for them to load up again and drift off deep into the wilderness. I know life is hard as the modern world encroaches on them but watching their lives enfold around me, I can’t help finding their way of life deeply romantic.

__________________