The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse.

Julien Levesque

[The study of Sindhi nationalism has remained over-determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state. The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. As a result, it has mainly received attention when sudden outbursts of violence seemed to threaten the stability of the state. However, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails. Rather than address questions of failure or success, this article shows that the construction of a nationalist “idea of Sindh” has been a continuous process throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It also illustrates how an aspirational middle-class played a central role in this process. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse. This process translated into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributed to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.]

Beyond Mobilization: The Broader Diffusion of the Idea of Sindh

While the promoters of the Sindhi nationalist discourse after Pakistan’s independence mainly belonged to an aspirational middle-class, the diffusion of the idea of Sindh impacted society more broadly. This impact appears in the widespread recognition of Sindhi identity markers as expressions of Sindhiness or even signifiers of Sindh. At the parades and shows that take place during the yearly cultural festival (the “Sindhi Saqafati Diharo” or “Sindhi Topi Day”) initiated in 2009, no one seems to question the constructed nature of the symbols that people brandish. To all, they are nothing but the symbols of Sindh.

To understand how the nationalist way of thinking about Sindh spread in society and changed the way people conceive of themselves and act in public space, one needs to apprehend nationalism beyond nationalist parties and beyond nationalist mobilization. Nationalism is not simply a political stance (i.e., believing in and advocating the independence of Sindh). It is also a social process – the transformation by which a particular criterion of belonging, such as an ethnic criterion, becomes the principal category through which individuals think of their society and its divisions. This redefinition implies that the link between the “cognitive dimension” of nationalism and “ethnic boundaries” is crucial to understanding nationalism. In other words, we need to look at the contest between people and groups of people in spreading or imposing their ways of thinking about the social world – and how, in this process, this same way of thinking about the social world is constituted and changes social relations. To better apprehend the broader contribution of Sindhi nationalism to Pakistan’s politics, this section examines how the idea of Sindh translated into the institutional realm – cultural policy on the one hand and electoral politics on the other.

Cultural Policy: Institutions for a Pluralistic Idea of Pakistan

Cultural Policy: Institutions for a Pluralistic Idea of Pakistan

The imprint of Sindhi nationalism is perhaps most evident in the realm of cultural policy. The historical and cultural narrative of Sindh as a distinct socio-political entity, although it infused the Pakistan project, soon clashed with the centralized and abstract conception of the Pakistani nation that was gradually defined in the 1950s and then promoted by the state after Ayub Khan took power in 1958. The nation-building project of the Pakistani state aimed at producing a citizen not defined by primordial attachments – linguistic, tribal, or caste-based – but by language (Urdu) and religion (Islam). This ideal pervaded the new teleological narrative that became official textbook history: authors like Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi and Sheikh Muhammad Ikram propounded, under the auspices of the Pakistan Historical Society and the Institute of Islamic Culture, a view of South Asia that sought to highlight the distinctiveness of Muslims, justifying the “natural” aspiration for a separate state that led to the birth of Pakistan.

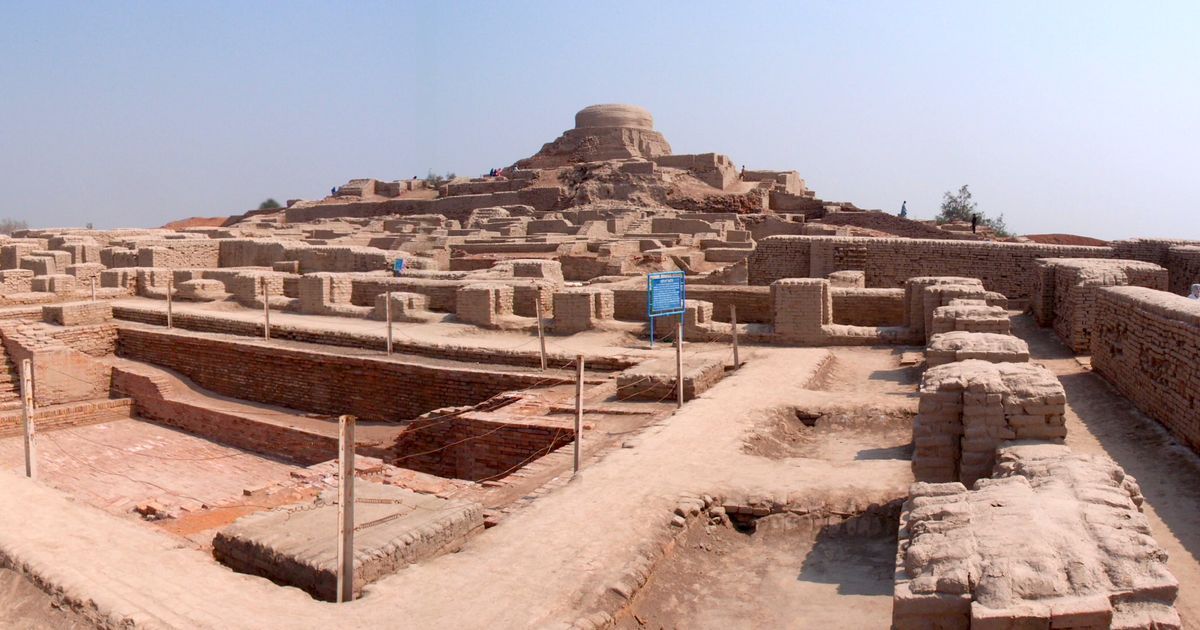

Against this official history, Sindhi researchers – historians, folklorists, literary specialists – elaborated on the narrative of Sindh sketched during the separation movement. While the idea of Pakistani-ness rested on abstract denominators of identity, Sindhiness was, in their view, concretely rooted in a shared cultural experience. This experience stretched since the days of Mohenjo-Daro and in concrete ties that made Sindhis one people – language and shrine-based religiosity standing out prominently in the list of collective binders. Not only did G.M. Sayed write books that expounded this political vision, but Sindhi researchers reinforced this myth of origins by invariably starting their inquiries from the Indus civilization, whatever the subject at hand. A good example of this approach is the influential Sindhi boli (Sindhi language) written by Siraj ul-Haq Memon in 1964. It describes Sindhi as the mother of Sanskrit and other north Indian languages, and the Indus civilization as a golden age that engendered both the Vedic and Mesopotamian civilizations:

[I]n the pre-historic era, there was a period in which a nation existed in the region extending from Harappa to Mohen-jo-Daro, i.e., from present Sindh and some areas of Punjab in its north, that was civilized in all aspects and possessed a fully developed civilized culture and had a spoken as well as written language. The people were disciplined, cultured, and more prosperous than other nations in the world … approximately in 5000 BC, this nation had a language that, with some exceptions, still prevails in the present-day Sindh region. It was a purely indigenous language which was free of any foreign influence.

Manan Ahmed summarizes the contemporary resonance of the opposition between Pakistan’s official discourse and the Sindhi nationalist narrative. He states: “The memory of a 5,000 year old Sindhi qaum is rigorously debated in everyday public spaces with just as much fervor as the originary myth of the nation-state of Pakistan is preached to the citizens of Pakistan.”

Interestingly, the scholars behind the Sindhi historical narrative worked with state support and provincial cultural institutions often sponsored their research. Like educational measures, such cultural institutions had their roots in government pre-independence initiatives at the provincial level. In 1940, G.M. Sayed, education minister in Mir Bandeh Ali Khan Talpur’s cabinet, founded the Central Council for the Support of Sindhi Literature (sindhi adab lae markazi salahkar board). This council, in December 1951, became the Sindhi Adabi Board. The SAB, headed by Muhammad Ibrahim Joyo, had serious ambitions concerning research and publication. Its program included writing a ten-volume history of Sindh (never completed), a linguistic project (grammar and dictionary), and a plan for folklore documentation that was to comprise 47 volumes. The person that was leading the latter project, Nabi Bakhsh Baloch, later became the director of another Sindhi cultural organization: the Institute of Sindhology, first established in 1963 as the Sindh Academy, before being renamed in 1970 in a way that, inspired by Indology or Egyptology, expressed its founders’ hope of constituting “Sindh Studies” as a recognized discipline. Nabi Bakhsh Baloch later coordinated the establishment of yet another cultural institution, the Sindhi Language Authority, in 1990.

Apart from the continuity in people, there was a palpable intellectual filiation, as these three institutions constructed a nationalist body of knowledge. On the one hand, Sindh-centric history-writing produced the material that a nationalist narrative could rephrase, which highlighted heroes of resistance against invaders and enemies. On the other hand, the folklore documentation project, drawing inspiration from colonial ethnography, collected, indexed, and hence fixed what scholars saw as the fast-disappearing Sindhi culture. The project categorized cultural diversity to create unity: a variety of ways of living and speaking, now labeled Sindhi, was presented in books and museums, such as the Sindh Museum in Hyderabad or the museum of the Institute of Sindhology in Jamshoro. Thus, cultural institutions engaged in a process of folklorization, which I define as inventorying and re-enacting cultural practices and references to turn them into essentializing, conscious identity markers eventually. The result was a conception of Sindhi culture reduced to specific elements – tales, songs, dress, and craftsmanship – now ready to acquire new political meaning as expressions of Sindhiness.

The cultural policy of “Sindhology” pursued in Sindh had an impact at the all-Pakistan level. When Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto came to power in the early 1970s, he bent the official unitary doctrine towards a more pluralistic vision of Pakistan and its population. Instead of defining the Pakistani citizen in terms of Islam and Urdu, official nationalism now acknowledged “regional” cultures as part of the “national” whole. To showcase this new state nationalism, Z.A. Bhutto had an international conference organized on Sindh in March 1975 (all four provinces were to have similar events). Perhaps more importantly, he established the National Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage, more commonly known as the Lok Virsa, in 1974. The Lok Virsa was a direct reproduction at the national Pakistan level of the Sindhi institutions and notably engaged in documenting Sufism and shrine culture as expressions of “popular” Pakistani culture. Z.A. Bhutto’s government officially promoted this inclusive nationalism, and the historical narrative was perhaps best phrased by the prominent PPP leader Aitzaz Ahsan, a reputed lawyer and former minister. In his book The Indus Saga and the Making of Pakistan, Aitzaz Ahsan dissociated the foundation of Pakistan from the two-nation theory and portrayed it as the logical outcome of a profound civilizational difference between Hind – the Gangetic plains – and Sindh – the Indus valley. Whether he knew it or not, Aitzaz Ahsan was reiterating a distinction that, drawn from medieval Arabic and Persian manuscripts, was central to Sindhi nationalist claims of cultural and political distinctiveness throughout history.

The official cultural policy of Pakistan, without discarding the state’s founding principles, fluctuated over time. After Z.A. Bhutto was ousted and hanged, Zia ul-Haq again emphasized Islam as the common denominator and patronized groups that promoted such a vision – religious parties and their scholarly organizations. Celebrating the cultural diversity of Pakistan – in Sindh, celebrating Sindhi culture – again became subversive. In this way, shifts in state policy displaced the limit between acceptable cultural assertion and inflammatory political statement, acting as a major structuring factor in what cultural institutions could or not publish. Yet folklorization is, by essence, equivocal. If folklorization can be an act of resistance against a homogenizing state policy, it may also serve to neutralize the subversiveness of identity assertion by representing the said identity as rigid “museified” cultural heritage. In Sindh, folklorized culture was used in different ways by Sindhi separatists and by Z.A. Bhutto and the PPP. The former extolled the folklorized vision of Sindh as the ultimate justification for their demand of independence. Conversely, Z.A. Bhutto used the same conception to assimilate Sindhi identity within a broader framework of Pakistani nationhood – depoliticized but preserved. This use would not have been possible without the intellectual and political engagement of the previous generations of Sindhis in constructing an idea of Sindh as a socio-political unit. (Continues)

__________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence.

Courtesy: Brill

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Click here for Part-I, Part-II, Part-III, Part-IV, Part-V