The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse.

Julien Levesque

[The study of Sindhi nationalism has remained over-determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state. The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. As a result, it has mainly received attention when sudden outbursts of violence seemed to threaten the stability of the state. However, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails. Rather than address questions of failure or success, this article shows that the construction of a nationalist “idea of Sindh” has been a continuous process throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It also illustrates how an aspirational middle-class played a central role in this process. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse. This process translated into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributed to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.]

Sindhi Nationalists and Sindh’s Political Arena

In mainstream electoral politics, Sindhi nationalism as a discourse and Sindhi nationalist parties have had a much more significant impact than their relatively low numerical strength may suggest. Journalists and commentators often decry the use, when the PPP seems to be losing ground in public opinion, of the so-called “Sindh card” – that is, the conscious reference by politicians to injustices committed against Sindhis by the Pakistani state. However, they rarely explain the appeal of such references for Sindhi voters, seeing only a misuse of public sentiment by shrewd office-seekers. Analysis should unpack this fact: how does Sindhi nationalism as a discourse connect separatist and autonomist parties with mainstream political agenda-setting in Sindh and Pakistan?

Such a question is approachable from the angle of political socialization. Many active members of the PPP, the Awami Tehreek, and the Jiye Sindh movement share similar social trajectories. Until the 1990s, they made their political socialization in the same context – the universities and colleges of Sindh – where they read G.M. Sayed, communist literature, and the poetry and stories written by Sindhi litterateurs since the 1950s. As a result of this intellectual training, they share a political outlook rooted in left-wing principles and nationalist leanings. However, they differ on the ultimate place for Sindh as independent or part of Pakistan and the strategies for reaching it (e.g., electoral, or non-violent opposition). They also often took part in the same struggles: although G.M. Sayed refused to support the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in the 1980s, many of his supporters chose to individually participate in MRD protests, as they considered it as a movement of resistance against the military regime, whose primary social moorings were in Punjab. As a result of a common political socialization, a large section of the Sindhi political class forms a network of interpersonal connections, sometimes dating to student days.

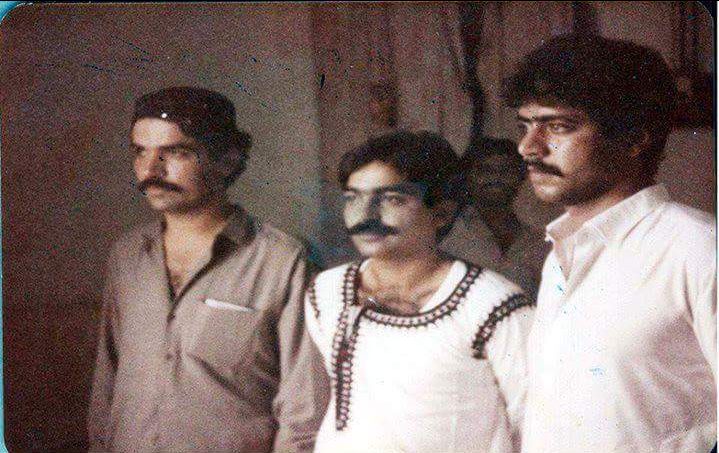

The common intellectual background and personal interconnections made it possible for many nationalists from Jiye Sindh and Awami Tehreek to defect to the PPP. One of the current stalwarts of the PPP in Sindh, Gul Muhammad Jakhrani, is a case in point. A man of the “third generation,” he asserted himself as a Sindhi separatist leader in the 1980s, and, along with Bashir Khan Qureshi, established a separate faction when the old guard of Jiye Sindh Mahaz refused to accept them on the allegation that they were involved in violent and criminal activities. He remained an active member of various separatist groups until the mid-2000s and eventually joined the PPP to run (successfully) in a by-poll election in late 2008. During his mandate as Member of the National Assembly (2008–2013), Gul Muhammad Jakhrani’s public interventions adopted an emotional, nationalist tone, arguing for the defense of Sindh’s rights, invoking the ancientness of Sindhi culture, and denouncing the injustices that Sindhis must now endure.

Such transfers of activists from Sindhi nationalist groups to mainstream parties – due notably to state repression and career opportunities the fringe par- ties cannot offer – have been happening since the 1970s, thus contributing to the diffusion of the nationalist idea of Sindh. The dense network between nationalist parties and the PPP – and, since the 1990s, NGO s – indicates that they participate in a single political arena, in which separatist parties have endorsed their own institutionalized space as pressure groups. Causes raised by nationalist and autonomist parties tend to be taken up by the PPP on the electoral stage and in elected bodies. There are specific issues on which the Sindhi political class stands united. One of these is the water-sharing problem, Sindh being in a dependent, riparian position in relation to upstream Punjab, Pakhtunkhwa, and Kashmir. In the mid-2000s, the autonomist party Awami Tehreek managed to garner significant support against the construction of the Kalabagh Dam on the Indus River after Pakistan’s President General Pervez Musharraf publicly revived the project in December 2004. Numerous political actors and intellectuals came forward, alleging that the proposed barrage would impact an already water-stressed Sindh. They signed a “Charter of Demands” that retold Sindh’s narrative of grievance from Pakistan’s inception and argued in favor of significant autonomy. About 900 people signed the charter drafted by the Awami Tehreek. Many political parties (including various autonomist parties, the PPP, religious parties such as the Jamiat Ulama-i Islam, the Punjab-based Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz) and civil-society or cultural organizations (such as the Sindhi Adabi Sangat and the World Sindhi Congress) supported it. According to the text itself, the charter was approved by “more than sixty thousand Haree [peasant] & mazdoor [laborer] activists.” Except for one signatory, however, Sindhi separatists were conspicuously absent from the petition because of its clear autonomist stance. While the Awami Tehreek was instrumental in building a platform to voice a united opposition, separatist groups who had not signed the charter mobilized public opinion by bringing people onto the streets, staging sit-ins, and conducting hunger strikes against the Kalabagh Dam project. Opposition by Sindhi politicians against the project has been constant since Zia ul-Haq pushed for it in the 1980s. The Sindh assembly has repeatedly voted unanimously in support of resolutions against the project, as have the provincial assemblies of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan. When the PPP came to power at the center in 2008, it chose to shelve the project, but the debate is regularly rekindled by politicians from Punjab, bureaucrats, or the military. This widespread consensus that translates into political decisions within the institutional realm stems from the sense of shared interest that rests in the belief that Sindh exists as a political community and is entitled to rights over its territory and population – in this case, the rights of a lower riparian.

This example shows that public controversies in Sindh are often constructed in connection with nationalist conceptions of the political community. This fact is possible because many Sindhi politicians in the PPP and other mainstream parties have experienced shared political socialization along with separatists on Sindh’s university campuses. Other examples could include questions of decentralization (the 1973 Constitution, the 18th amendment, Local Government Bill, NFC award), resources (oil, gas, coal), or the management of immigration (significantly, in recent years, internally displaced persons from the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas).

Conclusion: Co-constructed Nationalisms?

A key argument in this article is that focusing on whether Sindhi nationalism is or is not a failure has overshadowed much of what it has achieved. The incapacity of separatist and autonomist parties to shake the Pakistani state diverts attention away from better understanding the “idea of Sindh.” It deflects attention away from how nationalist principles inform understandings of Sindh and Sindhi identity and their broad diffusion in the Sindhi public sphere. Instead of focusing on failure or success, this article shows that constructing a nationalist concept of Sindh has been a continuous process spanning the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This process translates into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributes to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.

As this article highlights, the Sindhi nationalist discourse should be understood as socially constructed. Three generations of Muslim men, sharing similar trajectories but with distinct social characteristics and repertoires of contention, reinforced and disseminated it. After Pakistan’s independence, members of an aspirational middle-class crafted and promoted the idea of Sindh. Moreover, I showed that the production of the idea of Sindh implied a tremendous creative engagement on its proponents. In the process of “folklorization,” Sindhis identified specific cultural elements – notably Sufism and folk culture – that have been turned into identity markers by scholars before becoming ubiquitous in the public space, particularly in visual productions. With an aim to identity assertion, Sindhis established cultural institutions that were later replicated at the national Pakistan level. This paper also highlights the central role of G.M. Sayed as the founding father of Sindhi nationalism, both in the realm of ideas and institutions. Finally, this article opens the way for further study into the impact of Sindhi nationalism on society and politics in and beyond Sindh. Not enough is known about the way critics or opponents have engaged with Pakistan’s nation-building project. This article thus points towards the fact that scholars should examine Sindhi nationalism in its co-constructive relation with the Pakistani state’s conception of nationhood. Greater exploration of Sindhi nationalism and its relation to the Pakistani nation-building project would yield more detailed knowledge on the socio-political transformation that it induced. This exploration could start with missing or overlooked aspects of the narrative depicted here in this article. Examples include the 1940s Hur movement, the differing conceptions of “Sindhiyyat” by Sindhi Hindus and minority groups like the Sheedi, and the links between the various nationalist movements in Pakistan’s “smaller provinces.”

In recent years, the Pakistani state apparently seeks to subdue nationalist demands by replicating a Chinese model (i.e., economic growth through infrastructural investment with limited political rights). But nothing eliminates the possibility of new instances of widespread nationalist mobilization in Sindh. Since 2013, the Pakistani state’s severe repression of dissident organizations has targeted not only terror groups, but also ethno-nationalist political outfits (like the MQM in Karachi as well as Sindhi and Baluch nationalists). This crackdown has strongly weakened Sindhi nationalist parties after several years of heightened activity under PPP rule at the central level. Yet, the revival of Pashtun nationalism under the umbrella of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement suggests that there is scope for ethnic politics in Pakistan. For Sindh, the central authorities’ capacity to accommodate Sindhis within the power structure and grant them economic opportunities on par with Punjab and Karachi is likely to remain a significant determinant.(Concludes)

___________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence.

Courtesy: Brill

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

(Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Click here for Part-I, Part-II, Part-III, Part-IV, Part-V