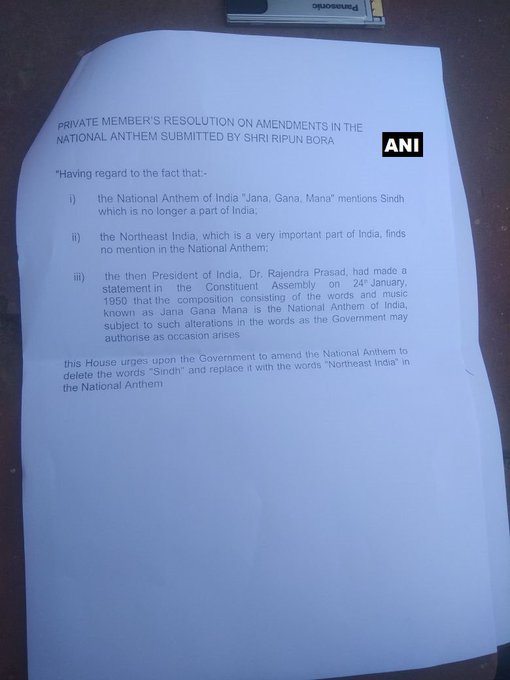

A private member’s resolution in Rajya Sabha in 2018 sought to replace the word Sindh in Rabindranath Tagore’s ode with North East India.

Saaz Aggarwal

You can take Sindh out of the national anthem but you are never going to get the national anthem out of Sindhis.

Though the Sindhis were evicted from their ancestral homeland during Partition, they continue to be amongst the most patriotic Indians, devoted to their community, language and traditions. Even when living and working abroad, they are Indian, with an abiding love and respect for their country of origin, to go with deep-rooted patriotism for their adopted countries. For the Sindhis who live in India, the situation is more complex. When Partition evicted them from their ancestral homeland, they were viewed as a liability, a burden on the resources of an impoverished nation. When they ignored the taunts and single-mindedly used their enterprise, hard work and common sense to progress, they were envied as opportunists and despised for the wealth and power they acquired; their immense philanthropy was conveniently ignored. Yet, their patriotism, a tradition of long-standing, never wavered.

Sindh, a province that came under the British much later than the rest of the country (1843) and where the process of colonization was more rapid and systematically goal-oriented, was a hotbed of protest. In 1942, when jails across the country were being filled with freedom fighters, Sindh had to be put under martial law. One of the unique and less-celebrated victories of the independence movement was the case of the Sindhi newspaper Hindu, inaugurated by Mohandas Gandhi in 1921. When its founding editor Hiranand Karmachand Makhijani was arrested and the press sealed in 1942, a replacement was appointed and the newspaper quietly resumed its revolutionary propaganda from another location. Eight subsequent editors were also arrested after periods of heroically continuing to publish it.

Hemu Kalani, too, has been deleted by the writers of Indian history. In 1942, he was captured for his revolutionary activities, put on trial and sentenced to death. The people of Sindh petitioned the Viceroy for mercy and it was granted – on the condition that he identify his co-conspirators. He refused. Hemu Kalani, 19 years old, was hanged in Sukkur jail. Families sat up through the night of January 21, 1943, waiting until his body was cremated.

On their own

Sindhis, conscious that their scanty numbers did not form an attractive vote bank, never asked for reservations in employment. After Partition, they hit the ground running and, launching into trade to support their families, built companies that would in time employ many. Neither did they ask for reservation in education; they built their own schools and colleges, many of which emerged from the refugee camps. In subsequent years, they contributed to healthcare, education, bureaucracy, industry, hospitality, and every other area of the Indian economy. Their foreign remittances from around the globe have only increased. The Sindhis lost their ancestral homeland, but quietly became a backbone of independent India. Still, across India, they continue to be derided as money-minded, tasteless and peculiar.

Hemu Kalani ceased to exist and so did Bhai Pratap. It was Bhai Pratap’s economic vision that made independent India aware of the concept of zones for duty-free export and led to the first such zone being established at Kandla in Gujarat. It was he who converted a remote creek into one of India’s most important ports, but there is neither acknowledgement nor appreciation of Bhai Pratap’s contribution in any public document pertaining to Kandla port, which was recently renamed for someone entirely unconnected with it. As for the jettisoning of LK Advani, who so successfully established divisive politics as a way to bring the Bharatiya Janata Party to power, the less said the better.

The Sindhis are no longer associated with Sindh. The generation that felt the pull of home is almost all gone. While a few might still hanker to travel to a forbidden land – and some to go there as a nostalgic tribute to beloved parents or grandparents – most Sindhis in India simply feel mighty relieved that their forefathers had the sense to leave the newly-created Pakistan and build new lives elsewhere.

Sindhis don’t care much about Sindh, but they do care deeply about being Sindhi and they do care deeply about being Indian. To remove the word Sindh from India’s national anthem would be to disgracefully strip away yet another layer of dignity from their identity.

A Rajya Sabha MP has moved a private member’s resolution, seeking to sabotage Rabindranath Tagore’s elegant verses for political gain by replacing Sindh in the national anthem with North East India. Who could blame the people who govern India for waking up to yesterday’s discovery that the North East makes a yummy vote bank?

And who could blame them for not working to develop the region and revel in its unique culture and beauty? Who could imagine they might want to understand the nuances of life in the region by going to live there? Or even by reading a book such as Ladders Against the Sky, written by someone who grew up there – the Sindhi businessman Murli Melwani.

____________________

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwa/ Scroll and Twitter

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.