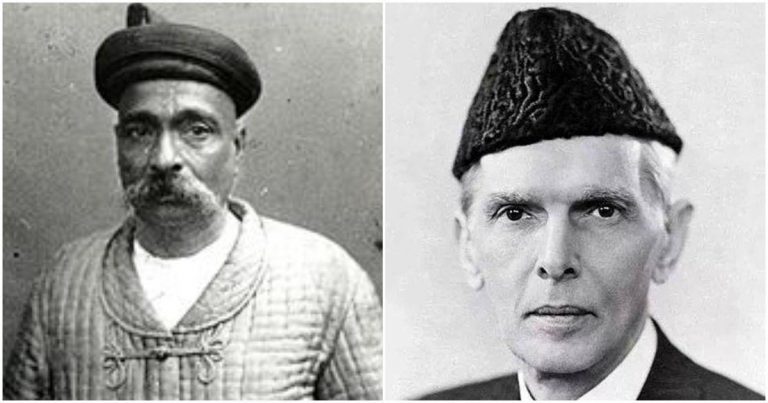

This association developed at a time when both the Indian National Congress, of which Tilak was a towering leader until his death on August 1, 1920, and the All India Muslim League, which later raised the demand for India’s Partition were themselves exploring a collaborative association to demand from the British self-rule for Indians.

Sudheendra Kulkarni

What a misfortune for India it was that no statesman – neither Mahatma Gandhi nor Jinnah – could ensure that the “two sister communities stood in absolute union” when the time came for the British to leave this land.

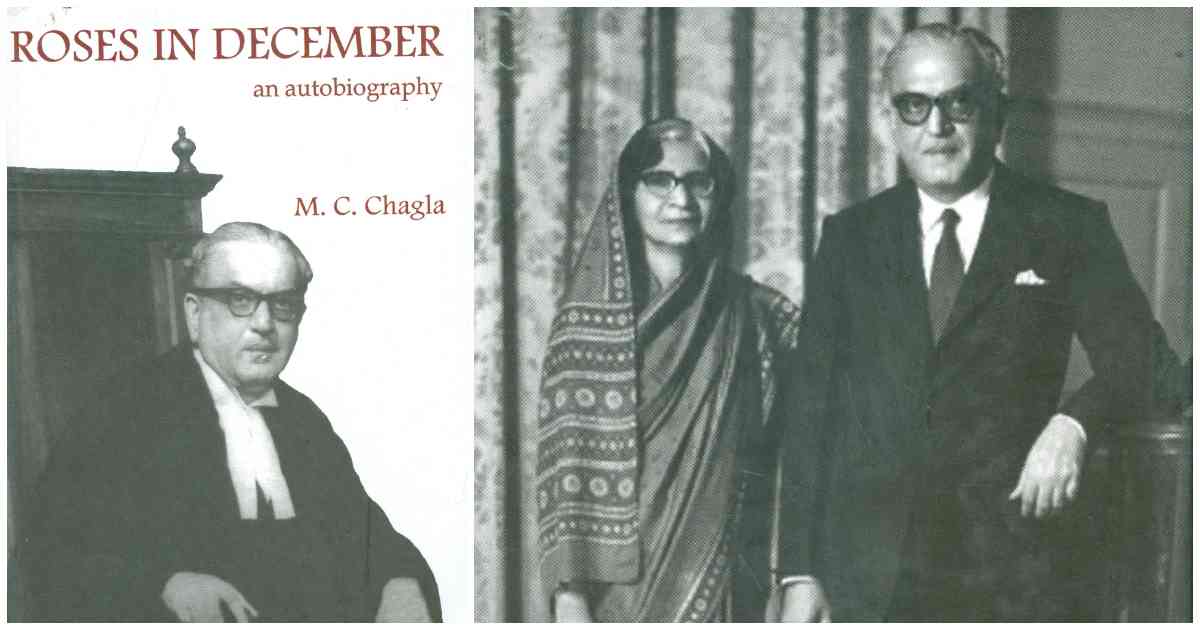

In the words of Justice Chagla

A perceptive account of Jinnah’s admiration for Tilak can be found in the autobiography Roses in December of Mohammedali Currim Chagla, the great jurist, who served as Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court from 1948 to 1958, and also later as India’s education minister. As a young lawyer, Chagla worked in Jinnah’s chamber. Tilak was his childhood hero. He idolized Jinnah and was also a member of the Muslim League although he quit the party after it started espousing the cause of Pakistan as a separate Muslim nation. His account is pertinent to this essay that it deserves to be reproduced here in extenso.

This is what he writes: “I might mention here that during my long association with him, I found that Jinnah always showed the greatest respect and regard for Tilak. Even when he was in the process of changing his political stand and becoming more and more communal, I never remember his ever saying anything which was derogatory of Tilak. Two persons in public life for whom Jinnah showed the greatest respect were Gokhale and Tilak. He had hard and harsh things to say about Gandhiji, Nehru and others; but as far as Gokhale and Tilak were concerned, Jinnah had the most profound admiration and respect for them and for their views.”

Chagla continues: “It is surprising that there should have been so much in common between Jinnah and Tilak. I understand that the regard Jinnah had for Tilak was reciprocated by Tilak. Jinnah told me that when as a junior he was reading in the chamber of Lowndes – Sir George Lowndes, who afterwards became a member of the Viceroy’s Legislative Council, and later still a member of the Privy Council –Lowndes’ opinion was once sought regarding some speech that Tilak had delivered. There was going to be a conference, and Lowndes asked Jinnah whether he had read the brief, and what he thought about it. Jinnah replied that he had not touched the brief and would not look at it as he wanted to keep himself free to criticise the government for prosecuting a great patriot like Tilak. Jinnah said that Lowndes was amused at the indignation and enthusiasm of his young junior.”

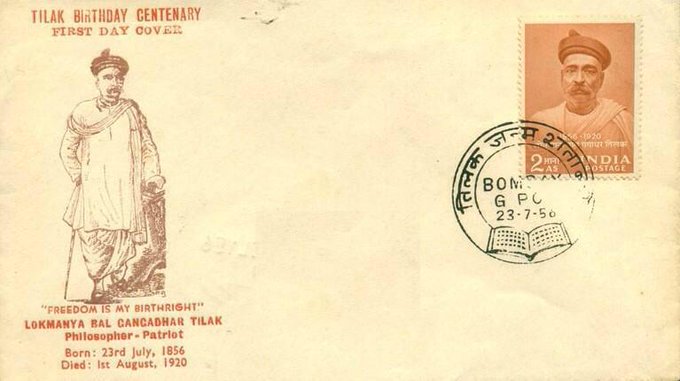

Chagla narrates another incident that highlights Jinnah’s respect for Tilak. “Jinnah also told me that after Justice Davar sentenced Tilak to six years’ rigorous imprisonment the Government conferred a knighthood upon Davar, and the Bar Association of the High Court of Bombay wanted to give him a dinner. A circular went round asking those who wanted to join the dinner to sign it. When the circular came to Jinnah, he wrote a scathing note that the Bar should be ashamed to want to give a dinner to a judge who had obtained a knighthood by doing what the Government wanted, and by sending a great patriot to jail with a savage sentence. It seems that Justice Davar came to know about this, and sent for Jinnah in his chambers. He asked Jinnah how he thought Davar had treated Jinnah in his court. Jinnah replied that he had always been very well treated. Davar asked him next whether he had any grievance against him [Davar]. Jinnah said he had none. Davar then asked: ‘Why did you write a note like this against me?’ Jinnah replied that he wrote it because he thought it was the truth, and however well Davar might have treated him he could not suppress his strong feeling about the manner in which he had tried Tilak’s case. All this goes to demonstrate the great regard which Jinnah had for Tilak, and also the courage and the spirit of nationalism which Jinnah displayed as a young man.”

What Chagla tells us thereafter demonstrates his own spirit of nationalism as well as his greatness as a judge.

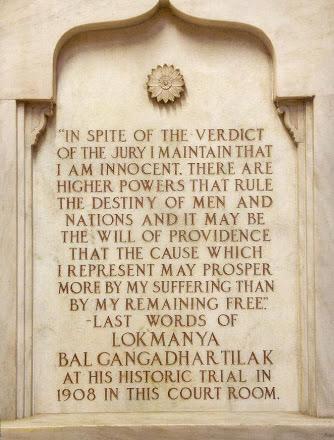

“By a happy stroke of fortune, I myself came to be concerned years later with this trial of Tilak by Davar in 1906. As Chief Justice of Bombay I had a tablet put up outside what used to be the Sessions Court in the High Court of Bombay on July 15, 1956.” In the speech he delivered on the occasion, Chagla said:

“There is no honor and no distinction which I have valued more than the privilege of being able to unveil the tablet to Lokamanya Tilak’s memory this morning. In this very room on two occasions within the space of 12 years, Lokamanya Tilak sat in the dock as an accused; and on two occasions he was convicted and sentenced to a term of imprisonment. We have met here today to make atonement for the suffering that was caused by these convictions to a great and distinguished son of India. That disgrace tarnished our record and we are here to remove that tarnish and that disgrace. It may be said that those convictions were a technical compliance with justice; but we are here emphatically to state that they were a flagrant denial of substantial justice. He was sentenced for the crime of patriotism. He was sentenced because he loved his country more than his life or his liberty. Ladies and gentlemen, the verdict that our contemporaries passed on us, the verdict that our times passed on us, is not of much value. We must always await the inevitable verdict of history; and the inevitable verdict of history is that those two convictions are condemned as having been intended to suppress the voice of freedom and patriotism, and the action of Lokamanya Tilak has been justified as the right of every individual to fight for his country. Those two convictions have gone into oblivion-oblivion reserved by history for all unworthy deeds. The fame and luster of Tilak has grown and increased with the passage of time…”

“May I be permitted a slight personal reminiscence – As a boy Tilak was always my hero. I remember the day when he was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in 1908, when I was a school boy studying in a school at Dadar; and I remember serious riots broke out in Parel; and so great was my anger and indignation at what happened to Tilak, that I almost felt like joining the rioters; but I suppose my deep law-abiding instinct prevented me from doing that. . . .”

In his autobiography, Chagla adds: “Referring to myself as occupying the post of Chief Justice, I said: “If today the High Court is functioning in a free India, if there is an Indian presiding as the Chief Justice of this Court, let us remember that it is due in no small measure to the suffering and sacrifice of Tilak.’”

Chagla’s action of unveiling the tablet in the Bombay High Court in honour of Tilak, with an inscription of his immortal words he as a convict had uttered in the court room in 1908, was subsequently criticized by some as an attempt to introduce politics into the administration of justice. However, “I remain unrepentant,” Chagla writes. “I think I did the right thing on behalf of myself as the Chief Justice, of my brother judges and of the High Court. Justice according to law becomes a rather empty and futile expression when you are dealing with a much greater and a more exalted force like freedom or patriotism and the love of one’s country. Therefore, without imputing motives to the judges who did their duty according to their light in convicting and sentencing Tilak, it was equally the duty of judges functioning in a free country to make it clear that what constituted a crime in British times had become a positive contribution to the freedom and progress of the country.”

Chagla concludes with yet another personal reminiscence. “I should like to add as a footnote to what I have written above that I myself met Tilak only once. This was in London during the time I was at Oxford and he had come there in connection with some litigation. If I remember right it was the Valentine Chirol case. I went to see him in the house where he was staying, and although I was a young student and he was a great national leader, he received me with great courtesy and cordiality, and we discussed various topics for a long time. I have no recollection now of the subjects we discussed, but I came away from that interview with a feeling of deep admiration for the great qualities of head and heart which Tilak possessed.”

It is well known that, at its session in Surat in 1907, the Congress had suffered a serious split between the “extremists” led by Tilak, Lajpat Rai, Bipan Chandra Pal and Aurobindo Ghosh, and the “moderates” led by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Pherozeshah Mehta and Surendranath Banerjee. The former had been expelled from the party.

The split had caused much anguish to Jinnah. It so happened that Tilak, too, after his release from Mandalay Jail in 1914, was keen on reconciliation. Tilak and Jinnah worked together on this task. The result was not only that the divided Congress re-united, but it also led to rare unity between the Congress and the Muslim League in their simultaneous sessions in Lucknow in 1916.

After Tilak’s death, Jinnah wrote a tribute in which he said:

“After his return from Mandalay, I came in closer contact with him and Mr Tilak, who was known in his earlier days to be communalistic and stood for Maharashtra, developed and showed broader and greater national outlook as he gained experience. I believe, it was at the Bombay Presidency Provincial Conference, over which I had the honour to preside, that the gulf, which was created owing to the Surat Congress split, was bridged over and Mr Tilak and his entire party once more came into the fold of the Indian National Congress in 1915. Since then, Mr Tilak rendered yeoman services to the country and played a very important part in bringing about the Hindu-Moslem unity which ultimately resulted in the Lucknow Pact in 1916.” (Concludes)

______________________

Sudheendra Kulkarni was an aide to India’s former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the Prime Minister’s Office between 1998 and 2004. As the founder of Forum for a New South Asia, he is actively engaged in efforts to strengthen communal harmony in India and also to promote India-Pakistan and India-China friendship.

Courtesy: Scroll

Click here for Part-I