Prose Poetry: From Chaos to Rebellion

Seeing the prose poem as a new genre may resolve many of the conflicts it has generated and disentangle the disputes between its advocates and opponents

Souad Khalil | Libya

This article seeks to explore the intertwined relationship between literature and dream, revealing the ways in which the dream—whether as a psychic impulse, a symbolic space, or an aesthetic structure—becomes a fertile source for creative writing. It examines how writers draw upon the dream world to construct narratives that transcend the boundaries of reality, opening the door to deeper interpretations of the self, memory, and imagination.

Within this framework, the article highlights the role of dreamlike expression as a form of artistic resistance, enabling the individual to reconstruct experiences and emotions through metaphor and poetic imagery. By doing so, it sheds light on the power of the dream not only as a personal refuge, but also as a creative catalyst capable of reshaping human experience and giving voice to what lies beyond language.

Amid the heated debate surrounding the identity of this literary form called “prose poetry,” the book ‘Prose Poetry from Baudelaire to the Present’ offers a significant contribution. In this work—translated by Jawad al-Taher—the researcher Suzanne Bernard traces the emergence and development of this form in French literature, making it one of the best available references that illuminate its artistic, thematic, and historical features. Through it, we see how prose poetry competes with traditional poetry and challenges its boundaries. But what is the nature of this poem, exactly?

The French scholar quotes Galo, who describes the prose poem as “a concise piece of prose, unified and compressed like a crystal that reflects a hundred different glimmers.” It is, he adds, a free creation with no necessity other than the author’s desire to construct it—escaping every definition, and compelled by an infinite gesture.

In his introduction to Bernard’s book, Mohamed Ibrahim Bousanna writes:

“The author perceives in it a kind of rebellion and an exercise of freedom within the human being’s continuous struggle against his destiny—more than a mere attempt to renew the poetic form. This means it may be a philosophical, social, and psychological phenomenon.”

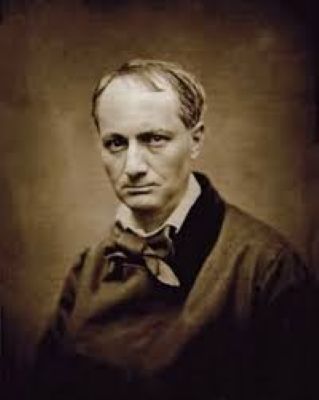

Baudelaire introduced the term *prose poem* in his collection *Paris Spleen*, translated recently by the poet Mohamed Ahmed Hamad. This came at a time when the Romantic Movement—brought to its peak by Victor Hugo in mid-nineteenth-century France—held absolute sway. It was an attempt by a new generation of poets to revolt against Romanticism, the very movement in whose shadow they had grown but from which they eventually broke away.

Bernard’s profound and evocative commentary suggests that this form belongs fundamentally to prose. She writes:

“There is no doubt that Baudelaire is the creator of a modern and urban poetry, born of strange sensations, in which the frightening merges with the comic, tenderness with hatred. Prose, which embraces the inner necessities of the human being with a grand sincerity, is more capable than verse of conveying the complexities of the modern heart and conscience—its leaps, its resentments, its longings for infinity, and its disillusioned skepticism. Through the prose poem, Baudelaire introduces new tones of irony, sarcasm, and cruelty into poetry. If he failed in most of his attempts at conventional verse, he appears, by contrast, remarkably able in prose to treat his lyrical, essential themes in unforgettable tonalities.”

Here, Bernard evades the confines of strict definitions of poetry and prose and turns instead toward content—the expansive space that prose provides to contain wild aspirations, leaps, and resentments. Baudelaire expressed the chaos of his age and the spirit of rebellion of his generation, and his constant anxiety over impending collapse. He writes:

“Symptoms of destruction, vast buildings piled one upon another… apartments, rooms, temples, corridors, staircases, labyrinths, compartments, lamps, springs, halves, fissures, cracks… Dampness rising from a warehouse near the sky. How can we warn the people and the nations? Whisper into the ears of the cleverest… On the highest point, a column cracks and its ends shift. Nothing has yet collapsed. And I cannot find the exit. I climb, then descend again—a tower of confusion from which I have never been able to escape.

I dwell in a building that will collapse—one eaten away by a hidden disease.”

Thus Baudelaire articulated, in the mid-nineteenth century, a nightmarish vision that would deeply influence his successors—especially Rimbaud, who declared: “Baudelaire is the king of poets.”

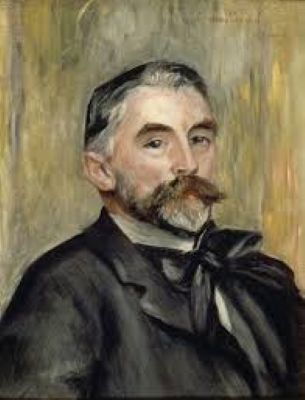

Baudelaire laid the foundations of Symbolism and built its strong pillar, influenced by his celebrated translation of Edgar Allan Poe. He unleashed the spirit of rebellion, which Rimbaud and Mallarmé would later continue. Rimbaud occupies a central place in the history of the prose poem because, as Bernard notes, he was “the first to point to the necessary relationship between the new poetic form and the quest for the unknown.”

In ‘Illuminations’ and A Season in Hell Rimbaud transforms the prose poem into a metaphysical enterprise more than an artistic form. He demanded that the poet become a seer, reaching the unknown through a long study involving a logical derangement of all the senses. The poet must become a “thief of fire,” like Prometheus, return from that realm, and make us feel and listen to his discoveries.

Rimbaud asked:

“How can these visions be translated into an old, ordinary form? How can the unsayable and the inaudible submit to the rules of meter and rhyme?”

The discovery of the unknown requires new forms; the verse line—declared “liberated” by the Romantics—still constitutes a barrier, preventing the soul from speaking to itself. He imagined that the poet must translate his vision more directly, without concern for stylistic traditions: he must find a language.

Chaos, then, is inherent in the nature of this mysterious form that seeks a mysterious vision through means that exceed logic, sensory capacity, and the conventions that shaped the distinctions between literary genres. Bernard questions whether Rimbaud ever truly reached the “unknown”:

“Are the visions that appear in *Illuminations* and *The Alchemy of the Word* anything other than hallucinations provoked by alcohol and drugs?”

The answer remains subjective. What we can ask instead is: to what extent does Rimbaud succeed in giving us the feeling of an unknown world—or rather, in *creating* that world through the evocative magic of poetry?

Bernard draws a connection between two of the movement’s most violent and rebellious figures: Rimbaud and Lautréamont. Both were young poets who came to Paris to mature their craft. Both were marked by violence and anarchic blending; both worked to destroy all literary conventions. They entered the prose poem in its most liberated form, expressing their individuality. Both renounced their pasts and abandoned literature quickly, leaving behind only death.

Thus, the prose poem becomes a manifestation of anarchic rejection of life in the time and place that shaped these poets. Bernard notes with astonishment that reading their works feels like confronting two young beings marching with full force, hopelessly, against society, against people, against love, against bourgeois morality—against every social element. They resorted to wild, individual means—savagery, sadism, hatred, sarcasm, anarchy. Their works represent the vast rebellion of maladjusted adolescents.

Thus, the prose poem becomes a manifestation of anarchic rejection of life in the time and place that shaped these poets. Bernard notes with astonishment that reading their works feels like confronting two young beings marching with full force, hopelessly, against society, against people, against love, against bourgeois morality—against every social element. They resorted to wild, individual means—savagery, sadism, hatred, sarcasm, anarchy. Their works represent the vast rebellion of maladjusted adolescents.

Bernard approaches a deeper definition of the prose poem when she observes that in Lautréamont’s work, it resembles both the story and the epic. She writes:

“We may say that *The Songs of Maldoror* break the narrow frameworks imposed on the prose poem as a highly defined genre. Lautréamont opened unknown horizons, for he definitively established the rule of propaganda in poetry—a dark propaganda inseparable from the imagination that interprets the reality surrounding the poet.”

In 1891, Rimbaud’s *Illuminations* and Lautréamont’s *Songs of Maldoror* were published, leading a new generation of Symbolists into the pathways of anarchic poetry. Mallarmé, another pillar of Symbolism and a writer of prose poems, completes the picture. Though his temperament differs greatly from Rimbaud and Lautréamont, he shares with them many traits. While they sought the unknown, Mallarmé pursued what Bernard calls “the stubborn Absolute”—a tenacious and often despairing Absolute. Yet all three affirmed the idea of ‘mystery’ in poetry, for they demanded that language bear more than it can bear, in their desire to reinvent it and restore words to their original power.

Mallarmé’s oeuvre astonishes: it reveals the struggle of a poet seeking a linguistic Absolute, constantly colliding with the resistance of language itself. It is an eternal struggle with—and through—words.

What seems impossible is to make language act against its own purpose: to convey something obscure in a way that is comprehensible and even beautiful.

Symbolism’s fires faded by 1897, but the twentieth century inherited and benefited from its legacy. Mallarmé’s struggle was not against anyone, but against chance itself, and on behalf of a spirit that aspired to make everything musical.

The term ‘prose poem’ thus continues to provoke contradictions in its meaning, intentions, and terminology. Bernard identifies two central poles:

– A destructive, anarchic force that seeks to tear down;

– And a constructive force aiming for a new, self-contained form.

The term ‘prose poem’ clearly reflects this duality: the writer of prose rebels against metric and stylistic traditions, while the writer of a poem seeks to create a closed, structured form.

Bernard argues that a difference exists between Rimbaud and other formalists: Rimbaud sought a poetic language that could record his visions and create the unknown—not merely an aesthetic stance, but a way of responding to the world as it is. She links classical meter to psychological balance and adaptation to the laws of existence; prose poetry and the poetry of chaos, by contrast, embody essential ambiguity.

This ambiguity lies at the heart of the prose poem: half negative, half active; mystical and magical. It is both a terrifying discovery and a creation of the unknown. The “seer-poet” is torn between the mystical necessity (using poetry as a means of knowledge and revelation) and the purely poetic or magical necessity—the creative ambition Rimbaud expressed when he wrote:

“I created all feasts, all triumphs, all tragedies. I tried to create new flowers, new stars, new bodies, a new language. I believed I possessed supernatural powers.”

Bernard comments:

“Undoubtedly, this creative ambition sooner or later drives the poet to want to control his eternal dream rather than be drawn passively by it. It inspires in him, as in Rimbaud, a demonic pride that ultimately leads to loneliness, impotence, and failure, confirming that poetry cannot change the world.”

Thus, the prose poem appears not only as a violation of a rule but as a futile attempt to abolish it altogether.

As for the Arabic prose poem, since its emergence in 1958 as a movement opposing the dominant nationalist trend in Arabic poetry, it has attempted to follow the model of the French prose poem. Its revival in the 1980s and expansion in the 1990s reflect a form of literary alienation expressed through linguistic rebellion. The French view of the prose poem—with its narrative tone, tension, concision, and rejection of rhythm—makes it resemble the short story, where dramatic intensity prevails in many examples.

It may be better, therefore, to view the prose poem—certainly prose, as its name indicates—as a new literary genre, perhaps born of an “illegitimate marriage” between poem and story, or of a mysterious interaction between poetic elements and the tribes of prose.

Seeing the prose poem as a new genre may resolve many of the conflicts it has generated and disentangle the disputes between its advocates and opponents. Yet it still conveys the sense of an Arabic guest at the table of French literature—one who arrived uninvited.

Read: The Source of Poetry

_______________

Souad Khalil, hailing from Libya, is a writer, poet, and translator. She has been writing on culture, literature and other general topics.

Souad Khalil, hailing from Libya, is a writer, poet, and translator. She has been writing on culture, literature and other general topics.