Death of Painting and Migration of Beauty

Painting has long been one of the most enduring witnesses to human civilization, carrying within its forms the traces of belief, power, beauty, and conflict

Souad Khalil | Libya

Throughout its long history, the pictorial artwork has never been merely a colored surface or a display of technical skill, but rather a civilizational witness to human transformations, a sensitive mirror of existential questions, dreams, conflicts, and tragedies. From the moment early humans traced their symbols on cave walls to the heights reached by painting during the ages of philosophy, the Renaissance, and modernity, visual aesthetics remained one of the most powerful languages capable of captivating the senses and opening horizons of contemplation.

However, the profound transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution—followed by colonialism, oppression, commodification, and the accelerated explosion of technology and knowledge—have once again raised the question of art and beauty: Is the painting still capable of fulfilling its civilizational role? Or has beauty abandoned it, just as humanity has abandoned the rituals of slow contemplation in favor of faster, more consumerist spaces?

This article proceeds from this pivotal question, seeking to deconstruct the notion of the “death of the painting” and the migration of beauty, not as the end of an art form alone, but as a sign of a deeper civilizational crisis that touches the relationship between human beings, art, and meaning itself.

This article proceeds from this pivotal question, seeking to deconstruct the notion of the “death of the painting” and the migration of beauty, not as the end of an art form alone, but as a sign of a deeper civilizational crisis that touches the relationship between human beings, art, and meaning itself.

Painting has long been one of the most enduring witnesses to human civilization, carrying within its forms the traces of belief, power, beauty, and conflict. From cave walls to museums and palaces, it once occupied a central position in shaping collective taste and aesthetic consciousness. Yet the profound transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution and modern technological life have unsettled this position. Beauty began to drift away from the canvas, while painting itself faced a growing estrangement from its audience. This article reflects on the notion of the “death of the painting” and the migration of beauty, examining the historical, social, and cultural forces that reshaped the relationship between artwork, artist, and viewer, and questioning whether painting truly failed its civilizational role—or whether civilization itself abandoned the conditions necessary for its survival.

Although many paintings throughout history have depicted scenes of combat and violence and portrayed heroes, they did not truly enter the realm of conflict as a central theme until after the Industrial Revolution. Their concept no longer corresponded to the old aesthetic order that harmonized with palaces, kings, and emperors. For the Industrial Revolution—despite the magnitude of its reciprocal impact on the development of thought, humanity, and production—was at the same time a fundamental cause of colonialism, oppression, hunger, subjugation, enslavement, and hatred.

The problematic relationship between civilization, producer, and consumer was not far removed from art. For a long time, the public remained merely a consumer of art, until theories of reception and interpretation confronted the audience with a major revolution by transforming it into a participant in the production of the artwork in order to grasp its beauty. The disappointment was profound when the painting found itself in one valley and its audience in another. Did the painting become incapable of fulfilling its civilizational role in our time when compared to the instruments of contemporary civilization, or did the audience fail to grasp its meaning and role in life?

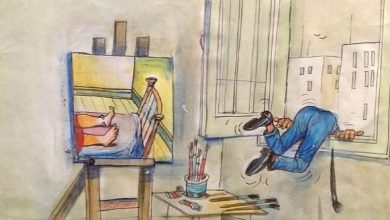

After a long journey marked by pain—beginning with cave walls, passing through museum halls, exhibition spaces, and palace walls—the painting declared its death, after beauty had abandoned it, never to return. Among the first to be struck by this death were the visual artists, who would cast aside their tools after the long journey had exhausted them and worn down their expressive struggles. Among its closest mourners were the critics, who never ceased interrogating it through various methodologies—sometimes praising, sometimes evaluating, and at other times condemning it. And among all those present at its funeral was its scant audience, which continues to roam between exhibition halls and auction houses—sometimes as buyers, sometimes as sellers, and at other times as forgers. Thus the painting announced its death, just as many sciences and arts had announced their final whim before it.

After a long journey marked by pain—beginning with cave walls, passing through museum halls, exhibition spaces, and palace walls—the painting declared its death, after beauty had abandoned it, never to return. Among the first to be struck by this death were the visual artists, who would cast aside their tools after the long journey had exhausted them and worn down their expressive struggles. Among its closest mourners were the critics, who never ceased interrogating it through various methodologies—sometimes praising, sometimes evaluating, and at other times condemning it. And among all those present at its funeral was its scant audience, which continues to roam between exhibition halls and auction houses—sometimes as buyers, sometimes as sellers, and at other times as forgers. Thus the painting announced its death, just as many sciences and arts had announced their final whim before it.

Dr. Iyad Al-Husseini, speaking of the death of the painting and the migration of beauty, asks: does that captivating magic that enchants hearts fade away?

This civilization, proud of its symbols of beauty and saturated with the luxury of expression, has long been accompanied by senescence. From early on, painting began as a religious symbol expressing rituals and beliefs, then folded itself under the cloak of philosophy when the elevation of subject matter in Greek civilization became an expression of glory and intellectual connection. It reached its extension during the Renaissance with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, then passed through stages of transformation in the nineteenth century at the hands of Cézanne, Manet, Monet, Van Gogh, and others.

Throughout its arduous journey, it moved between Classicism, Realism, Impressionism, Surrealism, Abstraction, Expressionism, Modernism, and Postmodernism—old and new alike—accompanied by generations of painters and sculptors, imposing itself upon many societies, perhaps the best of which were those in which the artist himself was miserable and pallid. Only the eyes of a conscious, cultivated elite contemplated it, delighted in its beauty, and grasped its meaning.

Although many paintings included themes of killing and violence and depicted heroes, they did not enter the theme of conflict until after the Industrial Revolution, when their concept no longer aligned with the old order that suited palaces, kings, and emperors. For the Industrial Revolution—despite the magnitude of its reciprocal influence on the development of thought, humanity, and production—was also a fundamental cause of colonialism, oppression, hunger, subjugation, enslavement, and hatred, when industrial nations needed resources and labor beyond their borders after their own resources proved insufficient to meet the demands of the new revolution. The only means of acquiring new resources was plunder, theft, and the enslavement of peoples.

The artist, as a human being, suddenly discovered that the bread he ate was soaked in humiliation, oppression, and servitude, and that the features of nature, splendor, and allure as symbols in the painted image were no longer capable of purifying that bread. The painting thus became a witness to the struggle between cruelty and pain, between exploitation and greed, between survival and annihilation. The symbols of beauty were transformed from signs of joy into a beauty that calls forth sorrow, pain, and misery, until the artist’s trust in capturing expressive symbols became a measure of the creative, subjective experience that testified to the capabilities of its creator throughout the twentieth century.

Undoubtedly, throughout its long history the painting has had numerous aims and diverse functions. Yet what ultimately remained was that enchanting magic we call beauty, in its many forms—the beauty that captivates hearts and bewitches minds. How desperately we have always needed doses of it, time and again, to make life possible. Lovers of beauty sought it with deep passion, while at the same time it meant nothing to the overwhelming majority of people.

The painting meant to beauty only what it carried and the directions to which it was connected. To merchants, it meant nothing more than pieces of wood fastened together with nails at four corners. But to the artist it meant a great deal: a condensation of lived experience, knowledge, and creative capacities that add something new to life.

Yes, it was that dose of beauty—the enchanting magic that possessed us for centuries as we searched for it across lands and societies. Yet beauty abandoned the painting after leaving museums and palaces. We no longer hear of people visiting museums or frequenting galleries, because the transformations of life and the prevailing climate welcomed the migrating beauty from museums into markets, streets, and homes. Technology, materials, substances, tools, and industries invaded every corner of contemporary life. Each product came to possess its own aesthetic advantages and necessities—a new kind of beauty that emerges through function, use, tool, and utility.

Yes, it is that dose of beauty that generates pleasure, no longer necessarily linked to a painting or a sculpture, but perhaps emanating from a mobile phone, a modern car, watching a film, or buying a new pair of shoes.

Technology and new materials were not the sole reasons for these transformations. The entry of numerous theoretical approaches and intellectual currents into painting also played a role. Painting no longer signified the superior skills of craftsmanship produced by mastery of technique, but became a visual, intellectual text subject to historical problems and difficulties of interpretation. This is natural, since painting lived within the intellectual climate that passed through society in all its transformations.

Thus it became commonplace to see decomposing remnants in an exhibition hall, or piles of waste from which we are expected to extract a dose of beauty imposed by the artist’s vision, or a single color field that the artist wants to convince us represents boundless pain.

The civilizational dilemma between producer and consumer was not far from art. For a long time, the public remained a consumer of art until theories of reception and interpretation confronted it with a major revolution, transforming it into a participant in the production of the artwork in order to comprehend its beauty. The disappointment was great when the painting stood in one valley and its audience in another. Did the painting become incapable of fulfilling its civilizational role in our time, when compared with the vocabulary of a different civilization, or did the audience fail to grasp its meaning and role in life?

The civilizational dilemma between producer and consumer was not far from art. For a long time, the public remained a consumer of art until theories of reception and interpretation confronted it with a major revolution, transforming it into a participant in the production of the artwork in order to comprehend its beauty. The disappointment was great when the painting stood in one valley and its audience in another. Did the painting become incapable of fulfilling its civilizational role in our time, when compared with the vocabulary of a different civilization, or did the audience fail to grasp its meaning and role in life?

The gap widened day by day until human beings found that the beauty obtained from a hamburger sandwich was better than a thousand incomprehensible paintings that meant nothing to them.

In one of its memoirs, the painting was closely associated with the age of Romanticism and prosperity, as it bestowed upon that era a complete and multidimensional image. It departed after we left the romantic age for an era of rebellion, political horrors, and oppression. Before bidding us farewell, it became incapable of expressing the movement of life shaped by rapid technology that no longer leaves us space for contemplation, reflection, or meditation.

As one of those struck by its death, beyond mourning its departure, I demanded from the painting more than it was created for, and felt disappointed when I did not find that the world had changed after I had completed it. Like other creators, I felt that this miserable birth meant nothing to anyone in the universe but myself, that it was nothing more than a witness to the tragedy of the human being since birth, and merely an expression of the bitterness of an eternal struggle that wished to leave nothing behind but despair.

The painting declared its death; the witness died, beauty abandoned it, and ugliness became the measure of truth, until tragedy was filed against an unknown perpetrator.

The proclaimed death of the painting reveals more than the decline of an artistic medium; it exposes a deeper crisis in the modern understanding of beauty and meaning. As beauty migrated from museums and galleries into markets, technologies, and everyday commodities, painting lost its privileged space as a site of contemplation and inner resonance. The gap between the artist’s existential vision and a consumption-driven public continued to widen, until ugliness was accepted as a new measure of truth. Yet even in its declared death, the painting remains a silent witness to humanity’s long struggle with pain, exploitation, and loss. Its absence does not signify the end of beauty, but rather its transformation into a dispersed, fleeting presence—one that continues to question our values, our choices, and the kind of civilization we are still willing to defend.

The proclamation of the death of the painting, as it emerges throughout this reflective trajectory, does not signify the disappearance of art so much as it reveals a radical transformation in the sites and criteria of beauty. Beauty has not vanished; rather, it has departed from its traditional spaces, migrating through streets, commodities, technologies, and functions, manifesting itself in new forms that no longer resemble those shaped by classical aesthetic consciousness. Between a painting that has lost its power to affect and an audience that no longer possesses the time for contemplation, the gap has widened to the point where ugliness has sometimes become the most truthful measure of expressing the tragedy of the age.

Yet the artist’s grief for the painting remains legitimate, for it once stood as a witness to a humanity that sought salvation through beauty rather than consumption. Perhaps the essential question is not whether the painting has died, but whether humanity itself has changed so profoundly that it can no longer listen to the call of beauty.

In this sense, the painting appears not so much dead as suspended between two eras, bearing witness to the fracture of an old relationship between art and life, and announcing—through its final silence—the tragedy of a civilization that has replaced contemplation with speed, meaning with utility, and beauty with the market.

Read: The Heritage in Theatre

_________________________

Souad Khalil, hailing from Libya, is a writer, poet, and translator. She has been writing on culture, literature and other general topics.

Souad Khalil, hailing from Libya, is a writer, poet, and translator. She has been writing on culture, literature and other general topics.