Power, Institutions, and the Poverty Puzzle

Prosperity without dignity is not development

Wealth flows upward; opportunity does not circulate. The state appears strong, but society remains fragile.

Noor Muhammad Marri, Advocate | Islamabad

The question of why nations prosper or decline is not merely an academic inquiry; it is a moral examination of power itself. Every society carries the imprint of its institutional choices—visible in its courts, its markets, its educational systems, and above all, in the dignity or humiliation of its citizens. This narrative is important not because it offers a new economic formula, but because it exposes an old political truth: poverty is not inherited, it is produced. Nations fail when power refuses to be accountable.

In post‑colonial societies, particularly in a country like Pakistan, this truth is unsettling because it deprives us of comforting excuses. Geography cannot be blamed, for regions poorer than ours have achieved prosperity. Culture cannot be blamed, for societies far more fragmented have managed to build functional states. What ultimately remains is power—who holds it, how it is exercised, and in whose interest. As Eqbal Ahmad warned, “States decay when power becomes an end in itself rather than a means of service.” This warning lies at the heart of this argument.

Institutions may broadly be divided into two types: inclusive and extractive. This distinction is not merely technical; it is deeply philosophical. Inclusive institutions are founded on trust in human potential. They assume that if people are provided security and freedom, they will innovate and create. Extractive institutions, by contrast, are built on suspicion; they assume people must be controlled, managed, and squeezed. One worldview trusts society, the other fears it.

Inclusive economic institutions protect property rights, enforce contracts impartially, and allow individuals the freedom to choose their occupations. More importantly, they distribute opportunity. They send a clear signal to society that effort will be rewarded rather than punished. Such institutions do not guarantee equality of outcomes, but they do ensure equality of possibility. This is why innovation flourishes where institutions are inclusive: once human potential is unlocked, it becomes the most reliable engine of growth.

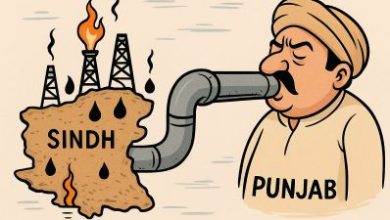

Extractive economic institutions, on the other hand, exist to benefit a narrow elite. They monopolize opportunity, restrict entry, and transform the state into a mechanism of rent extraction. In Pakistan, this reality is visible in protected sectors, cartels, and selective accountability. Laws exist, but they bend upward. As the late Justice Dorab Patel observed, “When law protects the powerful and disciplines the weak, it ceases to be law and becomes an instrument of domination.” This is extraction masquerading as order.

The central insight of this argument is that economic institutions are always subordinate to political institutions. Markets do not exist above power; they are embedded within it. Where political authority is unaccountable, economic inclusion becomes impossible. Development, therefore, is not a technocratic challenge but a constitutional one.

Read: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

Inclusive political institutions are characterized by pluralism and restraint. Power is divided, contested, and limited by law. No individual or institution stands above accountability. This idea echoes Montesquieu’s principle that power must check power, and Ambedkar’s insistence that constitutional morality must restrain social and political dominance. Inclusive politics is not founded on virtue, but on limits.

Extractive political institutions, by contrast, centralize authority and personalize rule. Decisions flow downward, but accountability never flows upward. Dissent is treated as disorder and opposition as disloyalty. Such systems often claim efficiency, yet what they truly fear is autonomy. They suppress society in the name of stability, failing to understand that stability without legitimacy is merely a postponed crisis.

Pakistan’s experience painfully illustrates this reality. The country oscillates between controlled democracy and overt authoritarianism, yet extraction remains constant. Faces change, but institutions do not. As Bacha Khan warned, “A nation that replaces its masters without breaking its chains remains enslaved.” Institutional continuity without reform produces stagnation, not progress.

This narrative also dismantles the comforting myth of ignorance—the belief that poor nations suffer because their rulers do not know what to do. The reality is more troubling. Elites often know precisely which policies would broaden prosperity, but they resist them because inclusion threatens privilege. Poverty, therefore, is not a failure of knowledge but a success of domination.

This pattern is global. Latin American oligarchies, African post‑colonial elites, Middle Eastern monarchies, and South Asian power blocs differ in form but not in function. They construct extractive institutions while speaking the language of modernization. Frantz Fanon captured this pathology with precision when he wrote that the national bourgeoisie merely replaces the colonial power without inheriting its capacity.

The idea of growth through coercion further sharpens this argument. The Soviet Union, early phases of China, and certain contemporary authoritarian states demonstrate that repression can generate rapid growth. Yet such growth is fragile. It relies on mobilization rather than innovation. Once easy gains are exhausted, repression replaces reform. As Hannah Arendt observed, violence can destroy power, but it cannot create it.

Inclusive systems may appear slower and more chaotic, but they possess a deeper strength: adaptability. They allow creative destruction to operate. Elites cannot permanently block change because power is not monopolized. This is why the Industrial Revolution emerged in England rather than Spain, and why technological leadership today remains closely tied to institutional openness.

The English experience, though incomplete, remains instructive. Inclusion expanded gradually and unevenly, but the subordination of the crown to law created a political environment in which economic inclusion could deepen over time. Progress was contested, not gifted. This lesson matters for societies that wait for saviors instead of building constraints.

Philosophically, this argument rejects determinism. Institutions are human creations, not natural laws. They are the outcome of choice, conflict, and compromise. Failure, therefore, is not destiny. Colonialism distorted institutions, but post‑colonial elites chose whether to reform them or inherit them unchanged.

In Pakistan, development is often reduced to infrastructure—roads, dams, corridors. This analysis reminds us that without institutional inclusion, infrastructure becomes extraction by concrete. Wealth flows upward; opportunity does not circulate. The state appears strong, but society remains fragile.

The moral core of this narrative is simple yet demanding: prosperity without dignity is not development. Inclusive institutions matter because they recognize individuals as agents rather than instruments. They create citizens, not subjects. In this sense, economic inclusion is itself a political ethic.

In closing, this is not merely an economic argument but a challenge to power. Nations do not fail because they lack resources or talent; they fail because those who rule fear inclusion more than poverty. Until power is constrained and fairly shared, growth will remain episodic and justice incomplete. Institutions shape destiny—and institutions are not accidents, but conscious choices.

Read: The Paradox of Merit

_________________

Noor Muhammad Marri is Advocate & Mediator, based in Islamabad

Noor Muhammad Marri is Advocate & Mediator, based in Islamabad