The Soomros were not conquerors from Central Asia or West Asia, nor were they aligned with major empires like the Mughals or Ottomans.

- Their ‘smallness’ in the grand imperial schema and their indigenous character meant they were often sidelined in histories written by imperial chroniclers and later colonial historians.

- Revisiting their legacy is not just about glorifying the past; it is about learning how local leadership, rooted in cultural empathy and social justice, can create sustainable and inclusive societies

By Abdullah Usman Morai | Sweden

Reclaiming the Indigenous Voice of Sindh

In the grand mosaic of South Asian history, few dynasties have been as historically significant yet systematically underrepresented as the Soomro Dynasty of Sindh. Flourishing between the 11th and 14th centuries, the Soomros were not just rulers; they were pioneers of native Muslim governance in a region long under foreign dominion. They marked a critical shift in Sindh’s political landscape, transitioning from Arab-Islamic colonial control to an indigenous Islamic rule rooted in local traditions. Despite their pioneering status, their story is absent from many mainstream historical narratives in Pakistan. This article aims to revisit their legacy, explore the nuances of their governance, culture, and challenges, and argue for their rightful place in the collective historical memory of the region.

Origins and the Rise of the Soomros

The Soomros emerged in the aftermath of the weakening Abbasid Caliphate and the decline of Arab control over Sindh. The region had been governed for over three centuries by Arab governors after Muhammad bin Qasim’s conquest in 712 CE. As the Abbasid authority waned, local tribal elites, particularly the Soomros, believed to be a Sindhi Rajput tribe that embraced Islam, began to consolidate power. This transition was not merely political; it symbolized a reassertion of Sindhi identity within an Islamic framework.

The founder of the dynasty, Soomar bin Rao Soomar, established control around 1025 CE, and his successors continued to strengthen their grip over key cities like Mansura, Thatta, and later Bukkur and Sehwan. The Soomros brought political power back to the local population, governing not as distant invaders but as sons of the soil, sharing language, customs, and cultural lineage with their people.

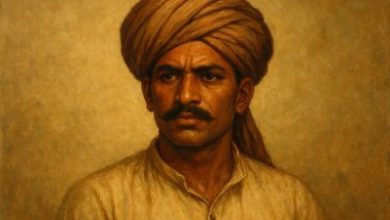

Dodo Soomro was a distinguished ruler of Sindh during the era of the Soomro dynasty, a period marked by resistance, pride, and the preservation of Sindhi identity. Dodo Soomro, one of its most iconic and legendary figures, is remembered not only for his governance but more so for his courage, honor, and unshakable commitment to Sindh. His rule symbolized Sindhi resilience in the face of foreign invasion and tyranny. Most famously, the story of Dodo Soomro’s stand against invaders, especially as portrayed in Sindhi folklore and poetry, has elevated him to the status of a national hero. The epic of Dodo Chanesar immortalizes him as a brave king who chose death over dishonor and defiance over submission. His legacy lives on in Sindh’s collective memory as a symbol of valor, self-respect, and undying love for the motherland.

Governance and Administrative Strategies

Soomro governance, though not documented in great administrative detail like the Mughal bureaucracy, showed a form of proto-feudalism mixed with tribal autonomy. They established a localized administration where tribal chieftains were integrated into the ruling apparatus through mutual allegiance. This ensured loyalty while allowing for the preservation of tribal traditions and power structures.

The capital city of Mansura became a vibrant hub of trade, culture, and scholarship under their rule. Agricultural policies ensured the maintenance of canal irrigation systems along the Indus, a vital lifeline for the agrarian economy. The Soomros also promoted fair taxation and land rights, practices that reflected their understanding of the peasant base of Sindh’s economy.

Cultural and Religious Synthesis

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Soomro rule was their approach to religion and culture. Unlike the orthodoxy of foreign rulers, the Soomros nurtured a unique synthesis between Islamic values and indigenous Sindhi traditions. They supported the growth of Sufism, which became the spiritual heart of Sindh. Saints like Lal Shahbaz Qalandar and Sachal Sarmast, among others, found fertile ground for their teachings even during, and short and long after the Soomro rule.

The Soomros used Sindhi and Arabic as court languages, promoting literary development. Oral history, poetry, and folk tales from this era reveal a culture where devotion, tolerance, and local identity were seamlessly integrated. Shrines, mosques, and educational centers flourished under their patronage, with traces still visible in towns like Thatta and Sehwan.

An interesting and unique cultural tradition among women of the Soomro community is that they traditionally do not pierce their noses, a noticeable distinction in a region where nose-piercing is a common and cherished part of feminine identity and adornment. While there is no single documented historical explanation, this practice is deeply rooted in the community’s values and identity. Oral traditions and cultural interpretations suggest that this custom is connected to notions of pride, dignity, and symbolic resistance.

According to some community elders and cultural scholars, the refusal to pierce the nose is believed to have originated during the time of Dodo Soomro and the Soomro dynasty’s resistance against foreign domination. The act of not piercing the nose may have symbolized the strength, independence, and unyielding spirit of Soomro women, representing their unwillingness to conform to foreign customs or to be ornamented for subjugation. It became a silent, generational protest and a badge of identity, preserving a sense of autonomy and self-respect. Even today, many Soomro women continue this tradition with pride, considering it a reflection of their historical roots and cultural dignity. This small yet powerful gesture ties them back to a time when even the smallest customs were infused with meaning and resistance.

Soomros in Verse: Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Shaikh Ayaz, and the Memory of Sindh

Soomros in Verse: Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Shaikh Ayaz, and the Memory of Sindh

Sindh’s great Sufi poet, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, and the modern revolutionary voice of Sindhi poetry, Shaikh Ayaz, both make references to the Soomros in their works. The Soomro dynasty holds an important place in Sindhi history, not only as a political power but also as a symbol of resistance, identity, and cultural pride. Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, in his verses, often evoked historical and legendary figures to highlight themes of bravery, loyalty, and the defense of Sindh’s soil, and the Soomros naturally found their place in this poetic universe. For him, their mention became a way of connecting spiritual wisdom with worldly struggles for justice and freedom.

Shaikh Ayaz, centuries later, also invoked the Soomros in his poetry, but with a more modern sensibility, linking their historical role to contemporary issues of identity, nationalism, and resistance against oppression. For Ayaz, the Soomros were not just rulers of the past; they symbolized the enduring spirit of Sindh and its people’s quest for dignity and autonomy. By mentioning them, both poets, Bhittai and Ayaz, created a bridge between Sindh’s history and its living cultural memory, making the Soomros an essential thread in the fabric of Sindhi literature and consciousness.

Foreign Relations and Conflicts

The Soomros ruled during a time when larger powers like the Ghaznavids and Ghurids were expanding in the region. Sindh, with its fertile plains and access to the Arabian Sea, was a coveted territory. The Soomros managed to retain autonomy largely through strategic diplomacy, intermarriage, and at times, military resistance.

For instance, when Mahmud of Ghazni attempted to extend his influence into Sindh, the Soomros resisted successfully, avoiding outright annexation. This act of defiance is often overlooked in Pakistani textbooks, yet it underscores their resilience. Later, the Delhi Sultanate under Alauddin Khilji posed another challenge, and while some Soomro territories eventually fell under imperial control, their core regions resisted full assimilation for decades.

Decline and End of the Dynasty

Like many dynasties, internal conflicts and external pressures led to the Soomro Dynasty’s decline by the mid-14th century. The rise of the Samma Dynasty, initially vassals or rivals, marked the next chapter in Sindh’s history. The Sammas, particularly under Jam Nizamuddin II, would go on to rule Thatta and further Sindh’s cultural and architectural heritage. Yet, they built on the foundations laid by the Soomros.

By the end of their rule, the Soomros had governed parts of Sindh for over three centuries. Their fall was not marked by catastrophic defeat but by a gradual absorption into emerging political realities. Many Soomros assimilated into local aristocracies, their descendants continuing to wield influence as landlords and spiritual leaders.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

In addition to Sindh, members of the Soomro community are also found in Pakistan’s Punjab and Balochistan provinces, as well as in the Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, reflecting the historical extent of their geographical presence.

Today, the Soomro name persists in Sindh, not just as a surname but as a symbol of indigenous pride. Politicians like Muhammad Mian Soomro, former Chairman of the Senate of Pakistan and interim Prime Minister, trace their lineage to the dynasty, consciously or unconsciously invoking this ancestral legacy.

Among the most revered modern heirs to the Soomro legacy is Shaheed Allah Bux Soomro, a prominent political leader and two-time Chief Minister of Sindh in the 1930s and early 1940s. Known for his commitment to communal harmony and opposition to colonial rule, he was assassinated in 1943 due to his independent stance and inclusive vision. His life and martyrdom echo the Soomro dynasty’s values of justice, autonomy, and service to the people. Allah Bux Soomro’s legacy is commemorated in Sindh’s political consciousness as a symbol of principled leadership and resistance against both sectarianism and imperialism.

Another notable example is Shaheed Abdul Razzaque Soomro from Moro, revered as a martyr for the Sindhi language. His sacrifice underscores that the Soomros have not only been defenders of Sindh but also staunch guardians of the Sindhi language.

In Sindhi nationalist thought, the Soomros represent a pre-colonial model of self-rule and cultural autonomy. They are invoked in literature, songs, and academic discourses as guardians of Sindh’s soul, defenders of its identity during an age of foreign encroachments.

One compelling case study is the restoration work at Makli Necropolis near Thatta, where some Soomro-era tombs have been discovered and preserved. UNESCO and local historians have pushed for greater recognition of this heritage, using the Soomro legacy as a rallying point for cultural conservation.

In popular culture, the story of Queen Zainab Tari, the legendary Soomro woman who reportedly ruled after her husband’s death, is frequently cited in feminist retellings of Sindhi history. This narrative reflects the inclusive and relatively progressive ethos of Soomro governance.

Why They Were Forgotten

The Soomros were not conquerors from Central Asia or West Asia, nor were they aligned with major empires like the Mughals or Ottomans. Their ‘smallness’ in the grand imperial schema and their indigenous character meant they were often sidelined in histories written by imperial chroniclers and later colonial historians.

Post-partition, the state focused its historical narrative on foreign invaders like Bin Qasim and Ghaznavid rulers to forge a religious identity. Local, nuanced histories like that of the Soomros were downplayed in school curricula.

Reclaiming the Soomros: A Call to Action

To correct this historical amnesia, academia and media must give due space to regional dynasties like the Soomros. Sindh’s universities should incorporate detailed Soomro studies into their syllabi. Museums must document their cultural contributions. Local historians and journalists have a key role in reviving public interest.

In a time when questions of identity, autonomy, and indigenous rights are becoming central in global conversations, the story of the Soomros offers both inspiration and historical grounding. They exemplify how a society can remain rooted in its cultural essence while embracing the universality of Islam.

Conclusion: The Legacy Lives On

The Soomro Dynasty was more than just a political entity; it was a cultural movement, a reclamation of indigenous agency, and a precursor to modern Sindhi identity. By combining Islamic principles with local traditions, by resisting foreign domination without rejecting progress, and by promoting religious pluralism and cultural expression, the Soomros created a model that remains relevant even today.

Revisiting their legacy is not just about glorifying the past; it is about learning how local leadership, rooted in cultural empathy and social justice, can create sustainable and inclusive societies. In a world torn between extremes of global homogenization and sectarian fragmentation, the Soomro Dynasty offers a forgotten but powerful middle path, a legacy waiting to be remembered and revived.

Read: When Systems Fail, Children Miss Education

______________________

Abdullah Soomro, penname Abdullah Usman Morai, hailing from Moro town of Sindh, province of Pakistan, is based in Stockholm Sweden. Currently he is working as Groundwater Engineer in Stockholm Sweden. He did BE (Agriculture) from Sindh Agriculture University Tando Jam and MSc water systems technology from KTH Stockholm Sweden as well as MSc Management from Stockholm University. Beside this he also did masters in journalism and economics from Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur Mirs, Sindh. He is author of a travelogue book named ‘Musafatoon’. His second book is in process. He writes articles from time to time. A frequent traveler, he also does podcast on YouTube with channel name: VASJE Podcast.

Abdullah Soomro, penname Abdullah Usman Morai, hailing from Moro town of Sindh, province of Pakistan, is based in Stockholm Sweden. Currently he is working as Groundwater Engineer in Stockholm Sweden. He did BE (Agriculture) from Sindh Agriculture University Tando Jam and MSc water systems technology from KTH Stockholm Sweden as well as MSc Management from Stockholm University. Beside this he also did masters in journalism and economics from Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur Mirs, Sindh. He is author of a travelogue book named ‘Musafatoon’. His second book is in process. He writes articles from time to time. A frequent traveler, he also does podcast on YouTube with channel name: VASJE Podcast.