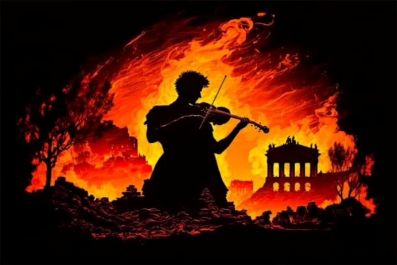

Nero Fiddled While Rome Burned

The comparison with Nero is not metaphor alone—it is a warning.

- Today, Pakistan faces a similar tragedy. Our state institutions are hollowed, sovereignty is fragmented, and the country drifts in a prolonged deadlock.

- Pakistan was neither created by civilians nor allowed to be governed by them.

By Noor Muhammad Marri, Advocate | Islamabad

History often repeats itself, not in the same costumes, but in the same drama. When Rome burned, Nero fiddled while the city went up in flames. He did not ignite the fire himself, yet history remembers him not only for the destruction, but for his indifference, his performance, and his deliberate distance from reality. The fire was not only physical—it was moral, institutional, and societal. Today, Pakistan faces a similar tragedy. Our state institutions are hollowed, sovereignty is fragmented, and the country drifts in a prolonged deadlock. And yet, instead of confronting the foundations of this crisis, our writers, poets, analysts, and conference-goers play tunes of their own: seminars on climate change, human rights workshops, cultural festivals, identity days, celebrity activism—all at a time when the architecture of the state is cracking. This is not mere distraction. It is deliberate design.

Since its creation in 1947–48, Pakistan has faced a persistent tension between popular expectation and structural reality. Early civilian leadership was removed or undermined not by the electorate, but by palace intrigue, bureaucratic maneuvering, and institutional vetoes. Between 1951 and 1958, seven prime ministers were replaced on one pretext or another, establishing a precedent that elected authority was conditional, not sovereign. Ayub Khan’s martial law did not disrupt this system; it formalized it. His promise of grassroots democracy, popularly known as Basic Democracies, was not intended to empower citizens—it was designed to contain them within pre-approved channels, allowing limited participation without challenging the centers of power. Local bodies became transmission belts for authority, not vehicles for it.

Since then, every civilian permutation has been attempted: Bhutto, Zia, Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, and their various permutations of populist, religious, dynastic, or technocratic governance. Yet each time, the architecture of power remained untouched. Governments changed, governance did not. Faces rotated, but institutions stayed insulated from accountability. The system learned an important lesson: civilian legitimacy could be borrowed without surrendering real power.

This historical lesson frames the contemporary moment. Today, Imran Khan is presented as another alternative, hailed as a populist hero by the same forces that sustain the system. Even if he returns with a two-thirds or three-quarters parliamentary majority, the structural reality will remain unchanged. Foreign policy is not made by parliament; it is embedded in strategic doctrines that predate every elected government. Defense expenditure is a sacred allocation, untouched by popular debate. The economy remains captive to external creditors and internal elite privileges; IMF dependence is not a policy failure, but a structural trap. The judiciary is selective and permanent; bureaucracies are unaccountable and immovable. Even angelic leaders, elected with overwhelming majorities, cannot escape these invisible ceilings.

This is the central tragedy of Pakistani civilian politics: failure is not a result of individual incompetence, but of systemic design. Elections change leaders, not power relations. Parliament debates, but does not rule. The executive administers, but does not command. The judiciary adjudicates selectively, often acting as a political actor without accountability. The bureaucracy remains permanent, insulated, and resistant to reform. Real authority is dispersed, opaque, and fundamentally untouchable by popular will.

In this context, the role of the writer, poet, and intellectual becomes decisive. Historically, writers have been the conscience of society, exposing lies, disturbing comfort, and challenging authority. In Pakistan, however, a large section of the intellectual class has been absorbed into the mechanism of delay. Co-optation has replaced censorship; recognition has replaced repression; conferences and international platforms have replaced prison or exile. Writers may appear radical, but their radicalism is carefully abstracted. Tyranny is never named; oppression is metaphysical; institutional power is invisible. Language is fiery, but content is safe. Emotional engagement replaces political accountability.

Cultural politics intensifies this effect. Debates over whether Karachi “belongs” to one group or Quetta to another, or the celebration of identity days and cultural festivals, are not mere expressions of pride—they are instruments of distraction. While citizens argue over symbols, they do not question the distribution of real power: who controls policing, revenue, land, ports, budgets, or security. Identity replaces citizenship. Emotion replaces agency. Celebration replaces confrontation.

Celebrities, meanwhile, act as anesthetics. Their statements personalize systemic issues, transforming political questions into lifestyle or social media debates. Their presence reassures the system that anger has been domesticated. Entertainers become moral authorities while institutional failures remain untouched.

The same logic applies to conferences on climate change, human rights, and rule of law. These are real issues in isolation, but when discussed separately from the centers of power, they become tools of delay and diversion. Climate change is debated as melting glaciers, not elite-controlled water mafias, land capture, or militarized development. Human rights are reduced to reports, not addressed as questions of coercive power or institutional accountability. Rule of law is framed as judicial training, not structural reform. Funding further defines boundaries: conferences financed by national and international establishments deliberately exclude foundational questions. Silence is purchased, not imposed.

This performative discourse serves yet another function: it internationalizes legitimacy while domestic legitimacy collapses. Panels, reports, and slogans convey an image of normalcy and governance to the outside world, even as the domestic state continues its drift. Decoration replaces action, noise replaces agency, and the boat continues to sink, even as the deck is polished.

In such a context, writers and poets often do not need to praise the establishment to serve it. Silence on foundational questions—who truly governs, why civilian authority is conditional, why accountability flows downward but never upward—stabilizes the system as effectively as active endorsement. When Rome burned, Nero fiddled; today, intellectuals play tunes, distract citizens, and postpone reckoning. Their words may be beautiful, their metaphors compelling, but their silence on structure is complicity.

This is why slogans about cities, identity days, or cultural events appear more often than discussions on civilian supremacy, redistribution of authority, or institutional accountability. People argue over symbols because the system fears collective political consciousness more than dissent itself. Horizontal conflict—between provinces, ethnicities, or communities—is encouraged to prevent vertical accountability, to prevent citizens from asking who owns the state. Safe conflicts and performative issues exhaust public energy and defer confrontation with the real centers of power.

The intellectual and cultural class, co-opted and absorbed, acts as a buffering layer. Their voices absorb dissent without altering structures. They provide the illusion of debate while ensuring the system remains immune to critique. Festivals, seminars, and symbolic celebrations produce moral satisfaction without producing political action. They anesthetize society in place of reform.

Pakistan’s crisis is therefore not a question of leadership. It is a question of architecture. Civilian failure is secondary to structural failure. Elections, dynasties, populists, and technocrats may rotate, but the distribution of authority, accountability, and power does not. Civilian supremacy was never permitted to be tested. Authority was ceded to institutions insulated from citizens, permanent bureaucracies, selective judiciary, and military prerogatives. Governance exists as ritual while power flows elsewhere.

Waiting for the next election, or hoping that a new hero will solve everything, is not hope—it is postponement. Time does not heal structural contradictions; it deepens them. Delay is not neutrality; it is deterioration. A system that blocks peaceful structural change long enough invites disruption from outside itself, often violently and unpredictably.

History teaches that collapse does not announce itself with slogans or panels. It arrives through exhaustion, cynicism, and silence. People stop listening. Language loses meaning. Authority becomes performative. At that moment, even the most sincere voices, if they avoided truth, are judged as complicit.

Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Pakistan’s writers, poets, analysts, and conference-goers may not have started the fire, but they participate in its management through distraction, diversion, and silence. Cultural celebration, identity affirmation, or environmental activism—important though these may be in isolation—cannot substitute for confronting the foundational crisis of civilian powerlessness.

The tragedy is clear: Pakistan was neither created by civilians nor allowed to be governed by them. Authority was ceded to structures insulated from public accountability. Civic consciousness has been deliberately fragmented into identity, symbolism, and performative engagement. Real questions remain unanswered: who governs, who decides, who commands? Until society confronts these questions, the state will continue its drift, and every hero, populist, or election will be absorbed into a cycle of ritual legitimacy without substantive power.

The intellectual class, in its silence or co-optation, stabilizes this drift. Festivals, conferences, and symbolic debates anesthetize society. Words replace action. Slogans replace reform. Noise replaces truth. In moments like these, silence is complicity, and distraction is survival for those in power.

The comparison with Nero is not metaphor alone—it is a warning. A state in structural decay, indifferent to its citizens, yet adorned with performance and spectacle, cannot be rescued by charisma or popularity. The melodies may be beautiful; the lyrics may stir emotion. But when the house burns, the music does not extinguish the flames.

Pakistan today stands at such a crossroads. The boat of the state is sinking, institutions are decayed, and sovereignty is fragmented. Conferences, celebrations, identity politics, and celebrity activism are the tunes played while the fire spreads. The question is no longer who will lead, but whether the state itself can be reimagined, or whether it will drift until collapse forces answers that courage refused to confront.

History is unforgiving: societies are judged not by the beauty of words, but by their courage in confronting truth. Those who fiddled while Rome burned were remembered forever—not for their music, but for the flames they ignored. Today, Pakistan’s writers, poets, and thinkers will be judged in the same way. Those who speak but never confront the architecture of power may not light the fire—but they help others ignore the smoke.

And that, in times like these, is not mere failure. It is complicity.

Read: Communal Justice: Mediation versus Judiciary

_____________________

Noor Muhammad Marri is Advocate & Mediator, based in Islamabad

Noor Muhammad Marri is Advocate & Mediator, based in Islamabad