My identity has a lot to do with my origins; with what and who I feel I am; with where I come from; with to where I feel a sense of belonging. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is because I was born and raised in a country and culture-of-the-land totally different to that of my parents’.

Pratap V Kripalaney-Dialdas

I was born in a small city (medium by Spanish standards) called Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, a group of islands that belong to Spain but are geographically located very close to the coast of northwestern Africa.

People have always simply called this place Las Palmas, a name well known in Sindhi circles as it is one of the enclaves around the world where a sizeable Sindhi diaspora somehow ended up settling, and with one of the biggest Indian communities in Spain. I don’t think I’d be wrong if I said that any Sindhi around the globe has probably at some point had a relative, friend or acquaintance living in Spain, and good chances are that that person was living in Las Palmas.

Surprisingly, over 95% of Indians here are Sindhis and we now have even third and fourth generation Sindhis here; however, statistics may not really portray the true picture of how many Sindhis or Indians live in Spain or the Canaries, as a majority have obtained Spanish citizenship, or were even born Spanish by law if their parents had already nationalized themselves beforehand.

My identity has a lot to do with my origins; with what and who I feel I am; with where I come from; with to where I feel a sense of belonging. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is because I was born and raised in a country and culture-of-the-land totally different to that of my parents’.

My identity has a lot to do with my origins; with what and who I feel I am; with where I come from; with to where I feel a sense of belonging. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is because I was born and raised in a country and culture-of-the-land totally different to that of my parents’.

Among people of my generation or circumstances, however, it may not necessarily be the same; the weight of their or their parents’ origin in their identities can be weaker or stronger. Some people feel closer to the land where they have been born and raised, others feel closer to their parent’s places of origin. And some, like me, are somewhere in the middle, in between two poles, where the shades of grey are infinite yet equally valid.

Today, being in the grey areas is a good feeling but it wasn’t so easy when I was a teenager and into my early twenties to figure out where I actually belonged. I felt divided between India and Spain. Sometimes I even had these crazy passing thoughts like, “If there was a war between India and Spain, which side would I be on?” or “Which side would I support in a hockey or football match between Spain and India?” Questions I could not answer.

I grew up loving planes and aviation and as a child I drew a lot of planes and made paper planes too, which would often carry an emblem or flag. Yes, you guessed it: either Spain’s or India’s (occasionally American or Soviet too, they had the best planes). My favorite airlines were of course Iberia and Air India and, as I write, I realize that more than for what they were as airlines, they were my favorites because of what they represented for me – my origins.

My brothers and I also loved flying kites as children – it’s something I miss today! They were the typical kites we get here in the West; when I saw the Indian kites in some Hindi movies I was fascinated by how simple yet colorful and beautiful they were and how fast they could fly and maneuver in the air. Wow, what an explosion of excitement it was, the day we accompanied Mom to the post office to collect a parcel that had arrived from India. In it there were a few dozen colorful patangs (paper kites) and manjhas (flying lines) that our Maasi Aruna had sent us, all the way from Bombay. A few were torn from the long parcel journey, but most arrived in shape, and such a treasure that we even repaired the ones we could. Whilst they lasted it was pure joy and pride to go fly them on our famous Las Canteras beach in Las Palmas. Imagine, Indian patangs in the Canary skies!

When I was around 12, I studied an academic year at a boarding school in Panchgani, where I had to learn how to read and write Hindi. As I could already speak it a little, it made things a bit easier, but at the time I found it an unnecessary waste of time to have to learn the language. Today I feel grateful that I did. Even though I do not read or write Hindi regularly or travel often to India, whenever I do, I always try to refresh my knowledge of the language by speaking it a lot and trying to read all the signs, titles and nameplates. I also love it when some of my Spanish work colleagues ask me to write their names in Hindi.

As for Sindhi, I do understand it but have never spoken it. Our Mom would speak to us in Sindhi often – and without fail when she was angry! But after her passing away, nobody speaks to me in Sindhi anymore. But thanks to internet I am very slowly beginning to watch some Sindhi parodies and may even start learning some Sindhi online. That’s some of what the digital age is doing for Sindhis. Having knowledge of Hindi and some Sindhi also makes me feel more connected to that part of me I guess, to the Indian and Sindhi part of my identity. A small thing that anyone living in India would take for granted, takes on another value here. But I must also say that a lot of Sindhis of my generation who were born here do speak Sindhi.

My parents, Manjari and Vashu, were always very proud of being Indian, and they tried to instill this sentiment into us. I think they were successful. They got married in Bombay in 1950 when they were still very young (25 and 17), but it was not unusual to marry at such an early age then. They moved abroad soon afterwards and spent the next 15 years in South America, living first in Caracas (Venezuela) and then in Curaçao (Dutch West Indies), where my father worked as a Bhaivar or working partner (in the Sindhworki system of employment) for the firm M Dialdas & Sons.

My Mom used to recount the funny anecdote that in those early years there were hardly any Indians or Indian businesses in those places, and that when they moved from Caracas to Curaçao, she was in fact the only Indian woman on the small island, so if she wanted to see another Indian woman she would have to look at herself in the mirror.

Despite their being so far away from India and there being so few Indians, they were always proud to celebrate Indian Independence and Republic Day and Gandhi Jayanti. As initially there were no Indian diplomatic missions there, they were sometimes invited to attend events as informal representatives of India. In Caracas, they were once invited and interviewed as guests on a TV series program dedicated to different countries, cultures and peoples from around the world, to speak about India.

A lot of my parents’ friends in those days were expat Americans and Europeans living and working like them in South America, and that included some diplomats; I am aware that on more than one occasion they had offered my parents a foreign passport, but according to my Mom, my father always said that he would never give up his Indian nationality for another one.

A lot of my parents’ friends in those days were expat Americans and Europeans living and working like them in South America, and that included some diplomats; I am aware that on more than one occasion they had offered my parents a foreign passport, but according to my Mom, my father always said that he would never give up his Indian nationality for another one.

My parents’ stories have had, and will continue to have, a lot of influence on me and my brothers, and our sense of belonging and connection to India. They instilled in us a sense of pride in India, even though we were not so conscious of it until we were older or more mature, and that sense of “Indianness” has permeated our Spanish side. Sadly, my father passed away in Las Palmas in 1977 when I was eight, but my mother continued to tell us about their experiences and thoughts and feelings.

Annual offering to Our Lady del Pino by the Indian community. Photo: author provided

My parents settled in Las Palmas in 1968, when my elder brother Vikram was not even two years old, and I and my two younger brothers, Lokesh and Manjit, were born here. People often ask how an Indian family ended up here in Las Palmas. In this age of migrations around the world that result from wars, hunger, refugee crises and illegal immigration flows, they tend to anticipate one of those scenarios.

But I tell them the true story. That my maternal grandfather, Bhai Pratap, passed away in London in August 1967 and that shortly before that, whilst he was sick and convalescing, he requested my father Vashu to go to London to be with him and help him with his affairs. My father reluctantly agreed, travelling from Bombay to London by ship.

The Suez Canal was closed due to the Arab-Israeli conflict, so ships plying between Asia and Europe had to circumnavigate the African coast, down to South Africa and up again to Europe, making the voyage much longer, and ships had to halt at ports of call to replenish and refuel. One of those ports was Las Palmas, and on his journey to London, my Dad’s ship stopped here briefly. He had never before set foot on the island and he liked the place very much and found that it had a lot of potential for future prospects.

He continued his journey to London, and my grandfather sadly passed away shortly afterwards. He returned to India, but the following year he decided to go back to Las Palmas and set up business, initially moving here on his own, and later joined by my Mom and elder brother Vikram.

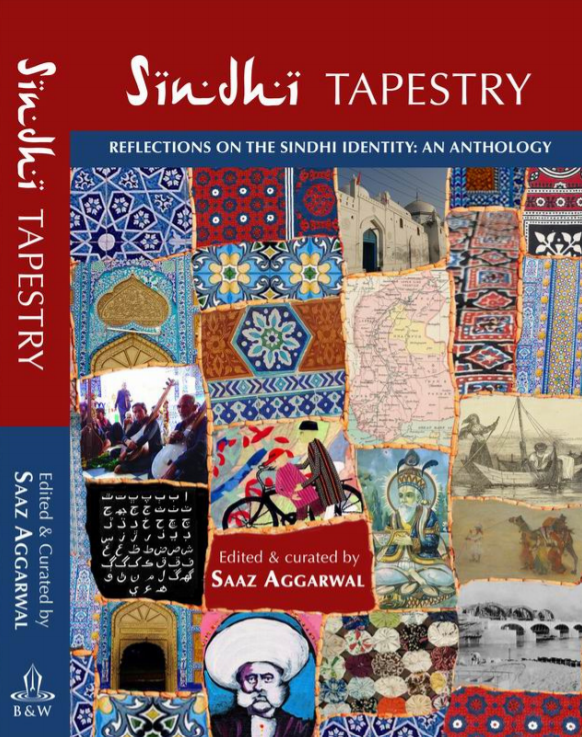

(Excerpted from Sindhi Tapestry: an anthology of reflections on the Sindhi identity. Edited and curated by Saaz Aggarwal. Published by black-and-white fountain.)

__________________

Courtesy: The Wire

The author is an airline professional based in Spain.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.