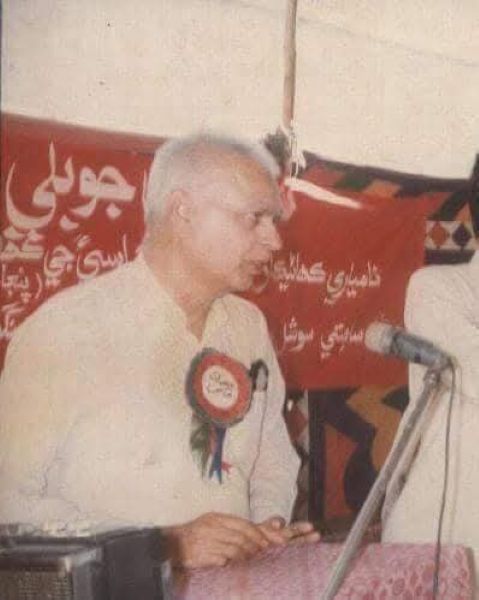

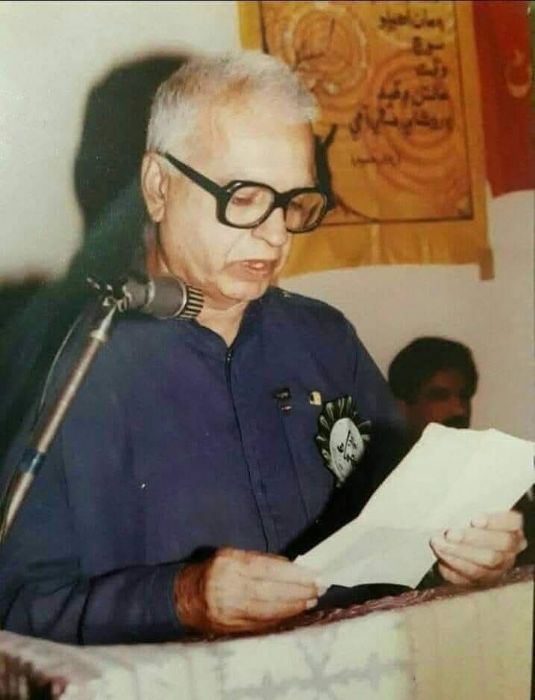

Najam Abbasi: Sindh’s Rebel Writer

Born on October 18, 1927, Dr. Najam Abbasi used the Sindhi short story as a weapon against capitalism, class inequality, tyranny, and exploitation.

By Manzoor Kalhoro

Since time immemorial, Sindh has been a repository of stories- a deep-rooted and flourishing tradition it has carried for centuries. The soulful, thematic, thought provoking and exalted tales appealed to the listeners and left them delighted, thrilled and thoughtful. Sindh’s folk literature can compete with any literature of any nation in socio cultural context and can be exceptional. Even today, Sindh’s folklore is so rich, lively, and exciting that if someone invests in it on modern grounds, it can rock and serve as a panacea for the psychological anxieties, despair, alienation, and restlessness of today’s world. If the heroines and heroes of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s poetry are staged in the remains of Ranikot, in the internal corners of Hyderabad fort, at the central space of Kot Diji, at the scorching sands of Thar Desert, in the fields of Makli or on the shores of Keenjhar or on the pinnacle of Gorakh Hill as similar as that of the theaters of Greece, Rome, France or Britain, then Sindh’s folklore would surely be a claimant of a global place in the international literature.

When British invaded Sindh in 1843 with their imperial claws, they were pleased to learn the fantastic Sindhi folk tales and therefore extolled it enormously. Having introduced the Sindhi alphabet, they either translated their short stories, novels, and dramas into Sindhi language or got them translated and thus introduced their literary arena, trends and movements in Sindhi literature. The invaders understood the dynamic trends of literature across the nations and resultantly predicted that the Sindhi storytellers would channel their creative intellectual powers into modern fiction, novels, and drama. That is precisely what happened. Sindhi writers not only translated Western fiction but, by the time of Partition, native Sindhi creative writers had displayed such creative literary excellence in these modern literary genres that today’s researcher is amazed at how, within less than a century, Sindhi literature stood shoulder to shoulder with modern world literature.

When British invaded Sindh in 1843 with their imperial claws, they were pleased to learn the fantastic Sindhi folk tales and therefore extolled it enormously. Having introduced the Sindhi alphabet, they either translated their short stories, novels, and dramas into Sindhi language or got them translated and thus introduced their literary arena, trends and movements in Sindhi literature. The invaders understood the dynamic trends of literature across the nations and resultantly predicted that the Sindhi storytellers would channel their creative intellectual powers into modern fiction, novels, and drama. That is precisely what happened. Sindhi writers not only translated Western fiction but, by the time of Partition, native Sindhi creative writers had displayed such creative literary excellence in these modern literary genres that today’s researcher is amazed at how, within less than a century, Sindhi literature stood shoulder to shoulder with modern world literature.

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent created a major rupture in this creative process. The trauma of migration and displacement temporarily silenced Sindh’s literary world. Yet, because Sindh has always nurtured creativity and creative impulse, this vacuum was soon filled. Before long, Sindhi poetry, stories, novels, dramas, essays, letters, and autobiographies again began to blossom and spread their fragrance throughout the region.

Sindh’s literature has always been the reflection of its land, its aspirations, of its people’s joys and sorrows, prosperity and suffering, struggles and resistance. Sindhi short stories have played a vital role in this expression. The Sindhi short story no longer needs validation or recognition as it has already been proven. This genre has produced exceptional, unique, and celebrated storytellers who have equipped Sindhi literature with masterpieces. When writers like Amar Jaleel, Ali Baba, Abdul Qadir Junejo, and Nurul Huda Shah adapted these stories into drama, Sindhi literature earned not only national but also international awards, recognition and reputation.

Today, the list of modern Sindhi short-story writers is long. Yet among them exists a “golden list” of legendary storytellers, and in the very front row of that golden list stands the name of Najam Abbasi. The time and clime in which Najam Abbasi breathed and wrote his masterpiece short stories was the golden age of Sindhi fiction. Every corner of Sindh- both urban and rural, near or remote, witnessed the eruption of brilliant storytellers who dedicated themselves to serve this literary art with their lifeblood. It was an era of socio-political unrest, intellectual strife, ideological discord, and literary idealism. In such extraordinary times, a variety of literary, political, and ideological magazines and journals were published like blossoms in springtime. As extraordinary times create extraordinary people, so was right about Najam Abbasi who carved out his own distinct identity at this critical juncture of life. Interestingly, this era of utmost socio political disturbances also gave Sindhi literature the iconic personalities who too excelled in the genre of fiction and lent Sindhi literature marvelous stories with great depth of socio cultural knowledge, insightful spirituality and utmost political wisdom. To relate this, the names of such icons are Jamal Abro, Amar Jaleel, Siraj, Agha Saleem, Ali Baba, Ghulam Rabbani Agro, Naseem Kharl, Qamar Shahbaz, Manik, Mehtab Mehboob, and Ghulam Nabi Mughal. Amid such giants, Najam Abbasi continued to distinguish himself through his own work.

What were Najam Abbasi’s stories about? They were about people like you and like me; peasants, laborers, the oppressed and exploited classes, the helplessness of women, social decay, tales of tyranny, political oppression, ideological conflicts, the pain of the poor, and the cruelty of feudal lords, chieftains, and landlords. His stories depicted the agonizing realities of the victims of brutality, the restlessness of the upper class, the longing for a revolution, for freedom, and about the ideals of love and devotion. These stories reflected his untiring dedication to the cause of Sindh and the Sindhi language and literature. Najam Abbasi did not belong to that opportunistic and self-serving literary fraternity that compromised for personal hen and gain and consequently harmed Sindh’s political and literary integrity. Instead, he used the Sindhi short story as a weapon against capitalism, class inequality, tyranny, and exploitation. His stories were reverberated the anguish of the common people. The themes he discussed were pertaining to real-life struggles and pain. Hence, he was a storyteller of the oppressed and working classes. Educated men and women alike admired his writings. No newspaper or magazine seemed complete without his contribution. Publishers across Sindh eagerly awaited his new stories, novels, or translations. And his books! Interestingly, his books always went sold as appeared, so much so that there isn’t a single publisher in Sindh who could claim to have charged Najam Abbasi for printing his books.

What were Najam Abbasi’s stories about? They were about people like you and like me; peasants, laborers, the oppressed and exploited classes, the helplessness of women, social decay, tales of tyranny, political oppression, ideological conflicts, the pain of the poor, and the cruelty of feudal lords, chieftains, and landlords. His stories depicted the agonizing realities of the victims of brutality, the restlessness of the upper class, the longing for a revolution, for freedom, and about the ideals of love and devotion. These stories reflected his untiring dedication to the cause of Sindh and the Sindhi language and literature. Najam Abbasi did not belong to that opportunistic and self-serving literary fraternity that compromised for personal hen and gain and consequently harmed Sindh’s political and literary integrity. Instead, he used the Sindhi short story as a weapon against capitalism, class inequality, tyranny, and exploitation. His stories were reverberated the anguish of the common people. The themes he discussed were pertaining to real-life struggles and pain. Hence, he was a storyteller of the oppressed and working classes. Educated men and women alike admired his writings. No newspaper or magazine seemed complete without his contribution. Publishers across Sindh eagerly awaited his new stories, novels, or translations. And his books! Interestingly, his books always went sold as appeared, so much so that there isn’t a single publisher in Sindh who could claim to have charged Najam Abbasi for printing his books.

Najam Abbasi, who wrote his first story titled “Himmat and Koshish” (“Courage and Effort”) in 1944, was a truthful, bold, and principled storyteller. Born into a middle-class family, the son of a schoolteacher Allah Andhi, he never accepted government servitude. He resigned from medical service and spent his life running a private clinic in Hyderabad, serving the poor and dedicating himself to literature.

By nature, Najam Abbasi was rebellious against oppression, tyranny, feudalism, spiritual exploitation, and capitalism. This rebellion began at early age when he read the revolutionary writings of Muhammad Usman Deplai in his father’s small library. Even in his final years of life, after being paralyzed for six years, he refused to give up. When he could neither write nor speak clearly, he still gave interviews from his daughter’s home. Those interviews have now become an essential part of Sindh’s literary history. They reveal how bravely and fearlessly he lived his entire life. Sindh will remain proud of writers like Najam Abbasi, who not only wrote about the sanctity and freedom of their homeland but lived those values in practice, standing firm against every form of oppression.

Born in October 18, 1927, in the small town of Khanwahan in the literary district of Naushehro Feroze, Sindh’s story teller Prince, Najam Abbasi passed away on October 25, 1995. On his grave are inscribed thought provoking words:

“When the day of Sindh’s freedom dawns, light a lamp on my grave as well!”

Sindh continues to preserve the intellectual legacy of this noble storyteller, through his works such as Toofan Ji Tamanna (Stories), Pathar Te Leeko (Stories), Gaarho Laaltain (Translation), Jeke Muhanji Mun Mein Aahi (Stories), Naachni (Stories), Aedo Soor Sahi (Autobiography and Essays), Rishta Nata (Stories), Akela Na Aahyun (Translation), Sooraj Hundi Murjhaail (Stories), Lalkar (Stories), Pahadan Mein Pukar (Translation), Pyar Kahani (Novel), Bulandiyan (Novel), Professor (Stories), Daroon Hun Diwani Jo (Stories), Kahani Jo Qaflo (Stories and Criticism), Gandhi (Translation), Tasawwuf Ji Cheer Phar (Essays), Talash (Novel), Zalzalo (Translation), Mastiriyani (Translation), Dokho (Stories), Mathe Sindh Sukar (Stories), Lenin Ji Inqilabi Kahani (Translation), Muhanji Behtareen Kahaniyun (Stories), Paan Mein Wetha Aahyun (Stories and Columns), Ocha Gaat Pahadan Ja (Stories and Interviews), and Jabal Mathe Bahri (Letters).

Let us preserve this legacy and let us renew our pledge to keep his light shining forever.

Read: Amar Jaleel: The Flame of Free Thought

___________________

Manzoor Kalhoro is a journalist based in Larkano, Sindh. Email: manzoorkalhoro2k16@gmail.com

Manzoor Kalhoro is a journalist based in Larkano, Sindh. Email: manzoorkalhoro2k16@gmail.com