Written in 1926, the travelogue was penned down by Vita Sackville-West as she embarks on an adventure from London to Teheran and back.

By Mahnaz Shujrah

“Of what use is it, if we may communicate our experience neither verbally nor on paper? And the wish to communicate our experience is one of the most natural, though not one of the most estimable, of human weaknesses.”- Vita Sackville-West

A book picked up by chance and read out of curiosity, Passenger to Teheran, turned out to be a journey halfway across the world and a hundred years back in time. Written in 1926, the travelogue was penned down by Vita Sackville-West as she embarks on an adventure from London to Teheran and back. The journey encapsulates multiple modes of transportation and changing terrains, from Egypt to India, across the Gulf to Iraq and onwards into the Persian heartland; on the way back, she shares a glimpse of communist Russia and Eastern Europe.

Vita Sackville-West was an established writer, poet and travel enthusiast, amongst varying other passions and interests. Descended from a well-known aristocratic family in England, she led a colorful life, most of which is described by her in her writings. She was friends with great personalities, including Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Bell, both of whom she mentions in Passenger to Teheran; she even shares details of her meeting with Bell in Baghdad. In 1926, she was traveling to Persia to meet her husband, Harold Nicholson, a diplomat who was posted in Teheran at the time. Sackville offers a unique point of view through her travels, both in an academic and philosophical sense, but it is her fervor for travel that makes the account worth reading. According to Sackville-West: “Nothing is an adventure until it becomes an adventure in the mind; and if it be an adventure in the mind, then no circumstance, however trifling, shall be deemed unworthy of so high a name”

Sackville-West authored around thirteen novels and another dozen poetry collections; she was a columnist in The Observer as well, where she wrote about gardening and landscaping. She, along with her husband, set up the garden in Sissinghurst Castle when they moved there, and through her writings, it became one of the most visited gardens in England. Her love for botany and nature contributed a great deal to her travelogue. She describes the blooms of different seasons through the plains and mountains of Persia; in her work, this establishes a level of intimacy not just with the writer but also with the land.

Baluchi tribesmen at the Coronation of Reza Shah

Unlike me, a reader familiar with Sackville-West’s background and writings may open this book with some preconceived notions, influenced by how they perceive the text. However, as a blank slate, I found myself pleasantly surprised at each turn. Sackville-West may appear to have a privileged view of the world, but she herself not only acknowledges that, but also breaks down that notion for the reader to digest. For one, she aptly provides a framework for how to approach travel writing; almost as if she were writing a research note before an ethnographic study. Furthermore, her poetic style beautifully conveys her depth of thought and introspection. I felt her writings were more stirring for the soul as she explores her own thoughts, as compared to more mainstream travel writings which are focused on the place. Even then, her firsthand account of certain events does provide insight, such as the coronation of Reza Khan in Teheran and revolutionary riots in Poland.

Her style of writing is such that at times she brushes over entire segments in a few paragraphs, while at other times she dwells in great detail on a single occurrence. This gives a text a certain level of excitement and unpredictability, as one can never know what catches the author’s eye.

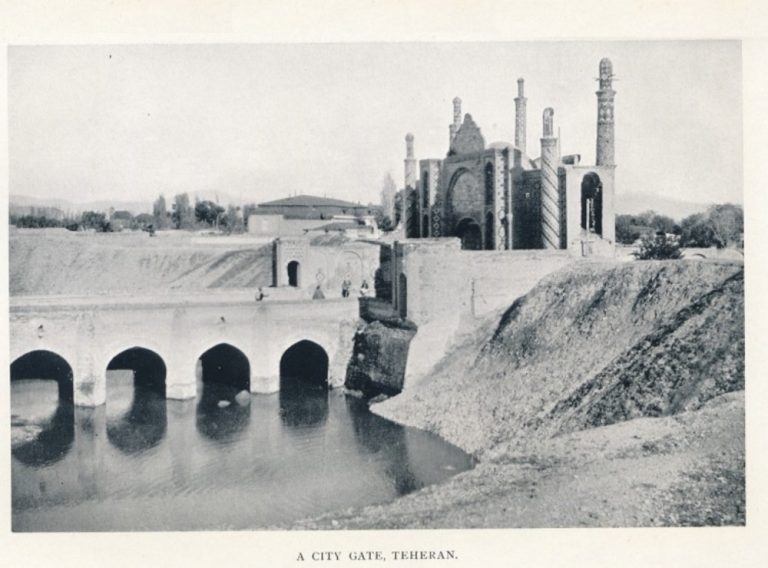

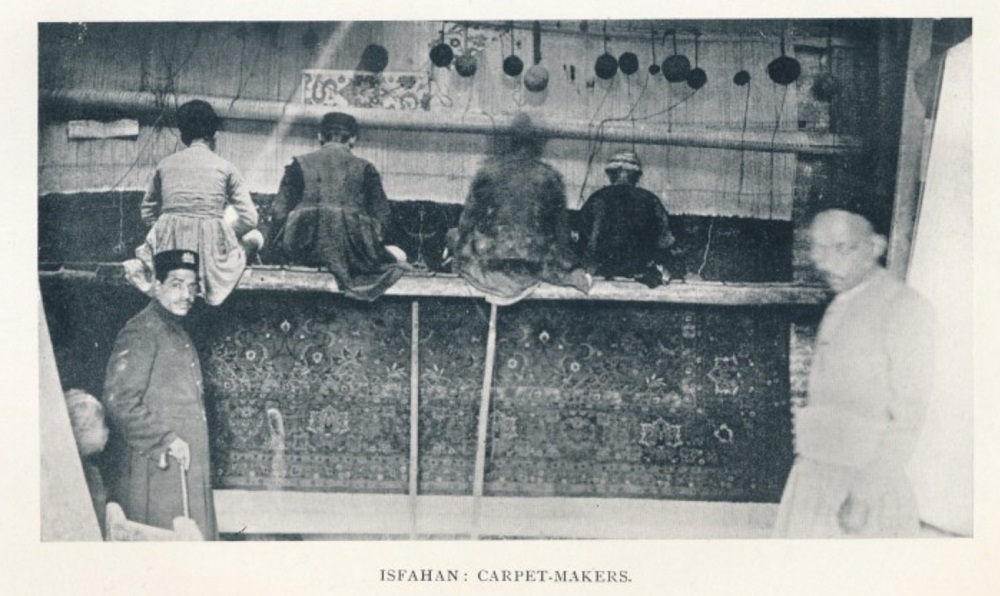

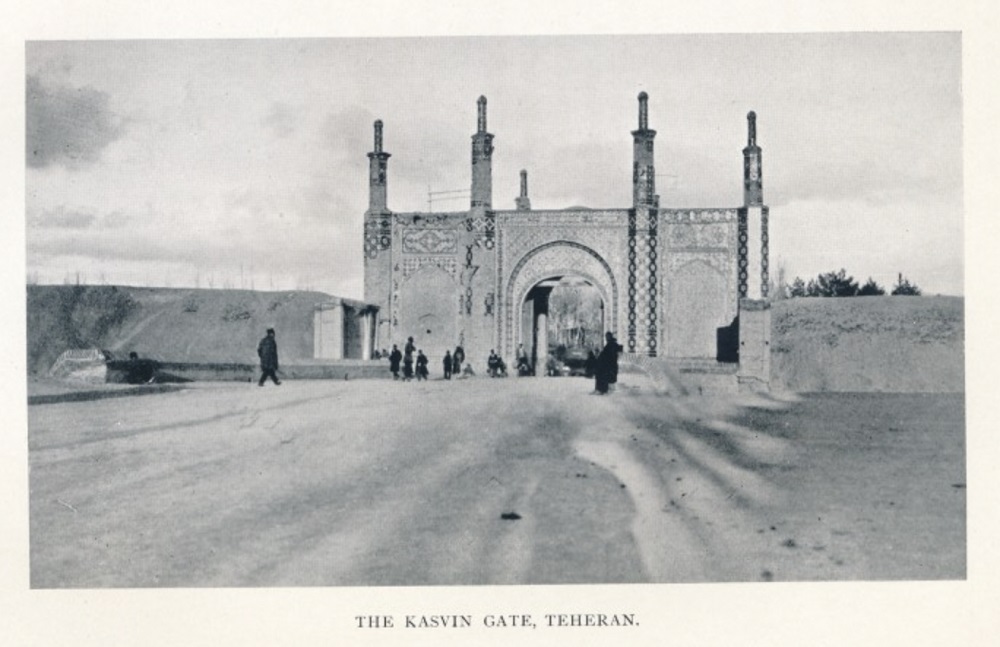

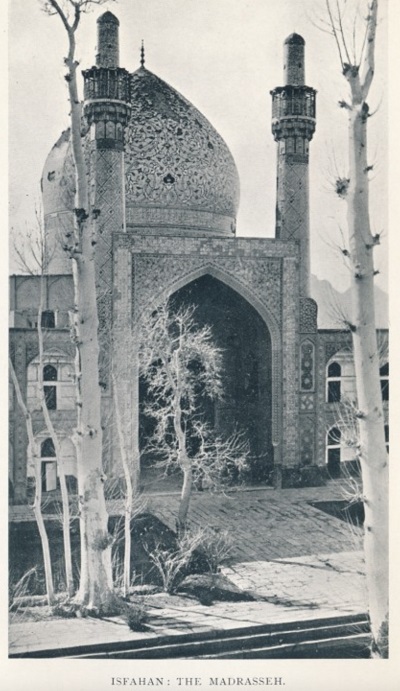

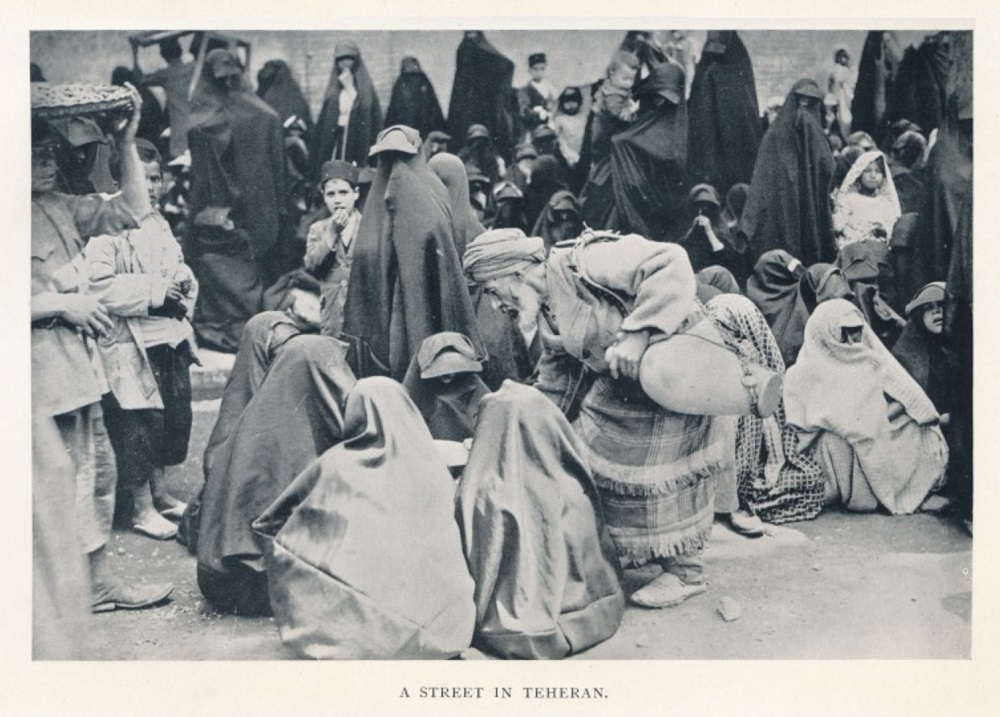

She enters Persia through Khaniquin, and describes the frontier. She spends a lot of time on the road to Teheran, during which she interacts with other travelers and nomads on the road, some photographs of which she shares alongside her text. The author explores the area within and around Teheran; she also takes a trip to Isfahan, to which she dedicates an entire chapter. Her favorite place in Isfahan was the Madrassa, which she describes as:

“if a school at all, then a school for pensiveness, for contemplation, for spiritual withdrawal; a school in which to learn to be alone (…) One is allowed to be lonely there, but in more civilized communities no one is allowed to be lonely; the refinement of loneliness is not understood. (…) The Madrasseh of Isfahan differed in this from the monastery, that it was the refuge of men ordinarily engaged in worldly affairs; merchants, traders, scholars, pilgrims, came here alike, for an hour, for a day; no conventions were binding; those who chose to be alone, might be alone, walking apart; those who chose, might drift into a little group, talking of current politics; those who would pray, might pray; but all were respected, in the indulgence of their several needs.”

What interested me most was the fact that Sackville-West was aware and mindful of her judgments as an “outsider”. She notices how Europeans behaved differently in their home countries as compared to “the East”. In her own words, “How curious a fact it is, that in a strange country, and more especially in the east, one should be so much concerned with the common people; at home one does not (except for more serious purposes) speculate about the secrets of the slums…”. An outlier amongst her European friends and company, she would much rather explore the land, not to study it, but merely because it was something which brought her pleasure. She conveys to the reader that her thoughts are merely her reflections, “For, personally, I prefer the bazaars to the drawing-rooms; not that I cherish any idea that I am seeing “the life of the people”; no foreigner can ever do that, although some talk a great deal of nonsense about it; but I like to look.”.

The book is a short read, but an excellent one. It offers the literary prose of a prolific writer, the eye-opening views of an avid traveler, the honest personality of a free-spirited woman and candid encounters with people from all walks of life. The text is accompanied by black and white pictures taken by the author and others, which beautifully supplement the writing, capturing and transporting the attention of the reader into a world, which is very different from todays.

____________________

Courtesy: Youlin Magazine, a cultural journal of Pakistan and China (Posted on: January 26, 2022)

[…] Read: Passenger to Teheran: A 1926 Travelogue […]