Sindhi literature has vanished into limbo of oblivion, and no excavation can give us an idea of the Sindhi literature earlier than the sixteenth century

By Menka Shivdasani

Modern Sindhi literature is generally divided into two periods—the British era (1843–1947) and the post-Partition phase, but its genesis was several centuries earlier, building on a rich tradition of Sufism (Mystic) thought and a synthesis of various cultures born of a series of attacks on this frontier province: the Aryans, Scythians, Arabs, Greeks, Iranians, Turanians, Mongols and Pathans have all marched through Sindh and left their mark.

According to Kirat Babani (Gehani 2006), historians agree that the oldest literature of mankind, the Rig Veda, was created here, on the banks of the river Indus, which was also known as Sindhu; indeed, when the Aryans arrived between 1050 BCE and 850 BCE, their fascination for the River Sindhu found expression in these words:

You bring great expanse of water

Lightning with a roar,

Like an unchained- horse

Bewitching and beautiful Sindhu

––’Sindhukasht’, a poet rishi’s composition in the Rig Veda (Gehani 2006)

According to L.H. Ajwani in his History of Sindhi Literature (1960), ‘The Sindhu has had a profound effect on Sindhi life and culture’, but its shifting character made Sindhi life unstable as the river constantly pushed its boundaries across the valley, wiping out whole towns, converting bustling ports into desert tracts. Rakhal Das Bannerji’s epoch-making excavations in the 1920s unearthed Mohen-jo-Daro, the Mound of the Dead, revealing that as far back as 3240 BCE–2750 BCE, Sindh had a civilization in many ways more advanced than that of Sumer or Egypt.

‘Sindhi literature has vanished into this limbo of oblivion,’ Ajwani writes, ‘and no excavation can give us an idea of the Sindhi literature earlier than the sixteenth century’. In his essay on Sindhi literature in the Sahitya Akademi publication, Contemporary Indian Literature (1957), Ajwani also notes that the first recorded Sindhi poetry is the verses of Qazi Qazan at the end of the 15th century, cast in doha form, and ‘uttering the note that is a constant feature in Sindhi poetry, namely that without the sight of the Beloved (or realization of the Infinite), external accomplishments such as scholarship and piety are so many monsters of the deep to drag one down to perdition’. Ajwani also observes that Qazan’s verse ‘bears witness to the most remarkable character of Sindhi poetry—the mingling of the twin streams of Hindu philosophy and Muslim faith to form the swelling waters of what is popularly known as Sufistic poetry (1957:254).’

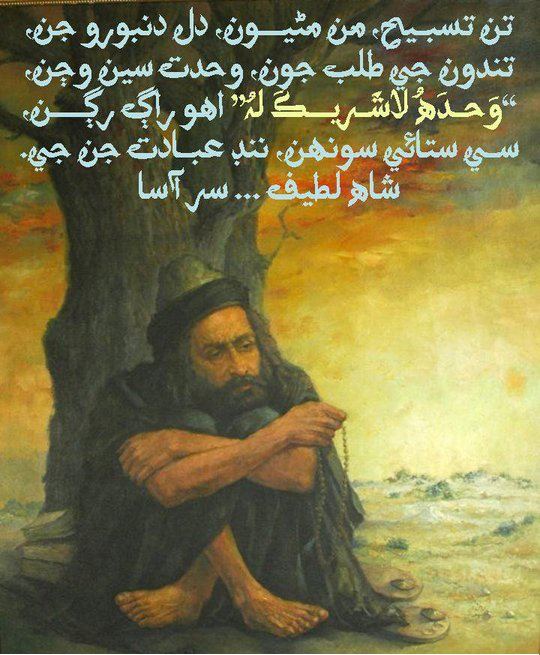

It was during the reign of the Kalhoros that the mystic poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (November 18, 1689 – January 1, 1752) made his presence felt. Shah Latif, often known as the Shakespeare of Sindh, ‘burst on the scene with his passion and his melody’, in the words of Ram Panjwani. His vocabulary was so rich, Panjwani writes, that a single word—camel—was named variously as ‘Uth’, ‘Karaho’, ‘Todo’, ‘Bodo’, ‘Chango’, ‘Dachi’, ‘Jangho’, ‘Goro’, ‘Kanvat’ and ‘Mahri’, to name just a few. In Latif’s vocabulary, the ascetic is a ‘Jogiaro’, ‘Lahooti’, ‘Veragi’, ‘Kapri’, ‘Babu Bekhari’, ‘Nango’, ‘Mawali’ and much more (Panjwani 1981). Shah Latif’s richly layered verses are still sung; his Shah-jo-Risalo has seen several translations and his simple tales are the subjects of Sindhi folklore. A recent translation of Shah Latif’s work in India is Seeking the Beloved (Katha) by Anju Makhija and Hari Dilgir, which won the Sahitya Akademi award in 2011.

It was during the reign of the Kalhoros that the mystic poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (November 18, 1689 – January 1, 1752) made his presence felt. Shah Latif, often known as the Shakespeare of Sindh, ‘burst on the scene with his passion and his melody’, in the words of Ram Panjwani. His vocabulary was so rich, Panjwani writes, that a single word—camel—was named variously as ‘Uth’, ‘Karaho’, ‘Todo’, ‘Bodo’, ‘Chango’, ‘Dachi’, ‘Jangho’, ‘Goro’, ‘Kanvat’ and ‘Mahri’, to name just a few. In Latif’s vocabulary, the ascetic is a ‘Jogiaro’, ‘Lahooti’, ‘Veragi’, ‘Kapri’, ‘Babu Bekhari’, ‘Nango’, ‘Mawali’ and much more (Panjwani 1981). Shah Latif’s richly layered verses are still sung; his Shah-jo-Risalo has seen several translations and his simple tales are the subjects of Sindhi folklore. A recent translation of Shah Latif’s work in India is Seeking the Beloved (Katha) by Anju Makhija and Hari Dilgir, which won the Sahitya Akademi award in 2011.

Shah Latif was the first and the greatest of what came to be known as the ‘Trinity of Sindhi Poets’: joining him were Sachal Sarmast (1739–1827) and Chainrai Bachomal Dattaramani Sami (1743–1850), who spouted Vedic wisdom in his Sindhi shlokas. ‘Shah, however, is the first and the foremost among these three ‘greats of Sind’, writes Panjwani (1987:29–30). ‘He brings the kettle to the boil, Sachal takes the lid off from it, while Sami passes on the beverage to the rank and file of the people so that they may be brought to an intense awareness of God, even when engaged in the day-to-day affairs of life.’

Panjwani himself was deeply influenced by this Trinity, and by Kishinchand Bewas (d. 1947), who founded the school of poets to which Panjwani belonged, along with Hari Dilgir, Hoondraj Dukhayal and Gobind Bhatia, among others (Ajwani 1957). Described as a Sufi by those who heard him, Panjwani—poet, singer, novelist, dramatist, short-story writer—carried forward the tradition, becoming a household name in the post-Partition era, spreading the message of love and Sindhi culture in the horrendous refugee camps where displaced Sindhis suddenly found themselves. ‘He has imbibed the Sufi spirit so well that he has become a worthy successor of the Sufi poets of Sind,’ wrote K.L. Panjabi, in a commemoration volume brought out on the occasion of Panjwani’s 70th birthday (1981).

Sindhi Literature and its Script: The British Impact

While the British struck a major blow to the Sindhi community by partitioning India and leaving the whole of Sindh to Pakistan, there is one sphere in which their contribution was positive—the development of the Sindhi language. Writing in 1957, L.H. Ajwani points out that the Sindhi script in use at the time was devised by British administrators 100 years earlier; because this script was Arabic in its characters, it disguised the fact that Sindhi is derived from Sanskrit and it is the oldest among all the Prakrit dialects that have emerged as independent Indian languages (1957).

As Popati Hiranandani (1924–2005), author of more than 50 books, explained to this writer in an interview six years before her death, ‘The Sindhi script has been nourished by Sanskrit, Arabic and Urdu, but it is not any of these in themselves. It is a combination; that is why the Sindhi script has fifty-two letters, while Urdu has twenty-six and Arabic twenty-two. Ours is a pure Sindhi script and we can proudly say that’ (Shivdasani 2010).

Hiranandani explained that in the early days, Sindhi had 12 or 13 scripts. ‘Then, when the British conquered Sindh and decided to make Sindhi the official language of the Province of Sindh, Sir Bartle Frere [Henry Bartle Edwards Frere], the first Chief Commissioner of Sindh, issued an order in 1851, which required all officials and civil servants to pass an examination in colloquial Sindhi,’ she said. A definite, distinct and standard script was needed. A committee of eight scholars—four Hindus and four Muslim—discussed the script for Sindhi and after long deliberations the present script of 52 letters was formed in 1853. It was the developed form of the already prevalent script known as Chaliha-Akhari. This full-fledged script incorporates four sounds peculiar to Sindhi, 13 sounds of Arabic and Persian, 33 sounds of Sanskrit, and a letter peculiar to Arabic, which is formed by the combination of ‘aa’ and ‘la’. The script has 23 letters more than the Arabic script.

As a post-Partition generation increasingly lost touch with this script, Hiranandani wrote a book titled Learn Sindhi in Ten Days. In more recent times, the Sindhi poet and playwright Vasudev Nirmal put together Self Sindhi Teacher, using innovative sketches to highlight similarities between Sindhi letters of the alphabet and images that a new generation could relate to—including kurta necklines, car headlights and children chewing gum! Sindhi literature lost a great stalwart when he passed away on April 10, 2017.

The Aftermath of Partition

The need for such books in the post-Partition era stems from the concern that the Sindhi language has few readers today. This is a direct result of the Partition of the Indian subcontinent, which uprooted the Sindhi Hindus from their homeland and caused untold violence. ‘The division of families and cultures through the drawing of national borders over ethnic, linguistic and filial identities seems the least horrific of Partition’s long litany of horrors…After all, the summer of 1947 left around a million people dead and at least 75,000 women raped and abandoned; about 12 million people were displaced; countless homes were abandoned or destroyed,’ writes Ananya Jahanara Kabir (2013:6).

Sindhi Hindus were the worst affected, losing their entire state to Pakistan, unlike Bengalis and Punjabis who still had some space to call their own. Travelling the world as unwelcome refugees, they learned to blend into their adopted cultures, gradually losing their very identity. As Popati Hiranandani explained to this writer, land and language are inextricably linked; if you lose one, you will eventually lose the other.

The first generation of post-Partition Sindhis in India, such as Ram Panjwani, its most visible symbol, made special attempts to keep the language and culture alive. Panjwani kept spirits raised at the miserable refugee camps by singing songs of Jhulelal, the River God, converting the deity into a symbol of unity for a scattered community; Prof. Mangharam Malkani (1896–1980), pioneer of modern Sindhi dramas, inspired a new generation of writers, gathering them to his literary classes at the Sindhi Sahit Mandal for 14 years, 1949 to 1962. In a video interview with this writer, Kala Prakash speaks of how they saved their precious annas for the bus ride to these weekly meetings.

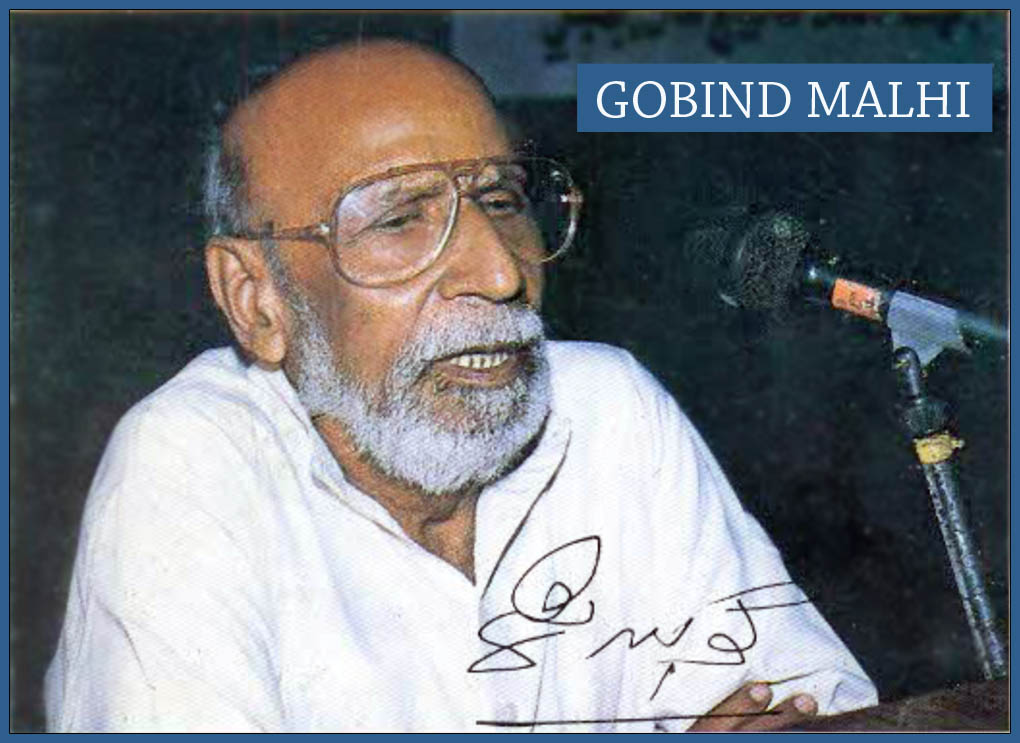

During this time, the Sindhyat movement also came into being, as Sindhis actively campaigned against the omission of their language in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. It took 20 years for the amendment to finally be made in 1967. Some of the key members of this movement were Gobind Malhi, Kirat Babani, A.J. Uttam and Mohan Gehani. This year, 2017, is a special one for the Sindhi community in India; it marks the golden jubilee of the inclusion of the Sindhi language in the Indian Constitution.

Meanwhile, as concerns over the perceived difficulties of the Persio-Arabic script began to grow, some Sindhis began to turn towards the Devanagiri script, as a way of keeping the language alive. The logic was that youngsters who knew Hindi would be able to read Sindhi if it was in the familiar Devanagari script. However, this was a controversial—and even violent—transition. Several Sindhi authors pointed out that a whole body of literature in the Persio-Arabic script would be lost as a result. Sindhishaan magazine noted in its July-September 2004 issue: ‘Multiple injustices of non-inclusion of Sindhi language in the VIII Schedule [of the Indian Constitution], as well as arbitrary imposition of Devnagari script for Sindhi language, created unrest throughout the Sindhis of India. Sindhi writers like Gobind Malhi, Bihari Chhabria, Dharamdas Khashtaria and others worked extensively to get Sindhi language its rightful place… A convention was held in 1954, at the very Convocation Hall of Bombay University (the same venue where it was earlier decided to change the Sindhi script to Devanagari), to constitute ‘Sindhi Boli Sabha’ in order to press for the implementation of Persio-Arabic script for Sindhi language, as well as to launch a campaign for inclusion of Sindhi language in the VIII Schedule of the Constitution of India’ (2004).

Meanwhile, as concerns over the perceived difficulties of the Persio-Arabic script began to grow, some Sindhis began to turn towards the Devanagiri script, as a way of keeping the language alive. The logic was that youngsters who knew Hindi would be able to read Sindhi if it was in the familiar Devanagari script. However, this was a controversial—and even violent—transition. Several Sindhi authors pointed out that a whole body of literature in the Persio-Arabic script would be lost as a result. Sindhishaan magazine noted in its July-September 2004 issue: ‘Multiple injustices of non-inclusion of Sindhi language in the VIII Schedule [of the Indian Constitution], as well as arbitrary imposition of Devnagari script for Sindhi language, created unrest throughout the Sindhis of India. Sindhi writers like Gobind Malhi, Bihari Chhabria, Dharamdas Khashtaria and others worked extensively to get Sindhi language its rightful place… A convention was held in 1954, at the very Convocation Hall of Bombay University (the same venue where it was earlier decided to change the Sindhi script to Devanagari), to constitute ‘Sindhi Boli Sabha’ in order to press for the implementation of Persio-Arabic script for Sindhi language, as well as to launch a campaign for inclusion of Sindhi language in the VIII Schedule of the Constitution of India’ (2004).

Now, as this diaspora community connects over the Internet, there is a move to bring in a Roman script as well. The website, www.romanizedsindhi.org, was hosted on December 31, 2010, under the auspices of the Alliance of Global Sindhi Associations Inc, coordinated by Arjan T. Dawani of Singapore. A dictionary, published in 2011 by the Indian Institute of Sindhology, contains both the Devanagiri and Roman scripts.

Sindhi Poetry

Through all this unrest over the script, the exclusion of Sindhi from the Indian Constitution, and the difficulties that refugees had in rebuilding their lives, poetry continued to make its presence felt.

Baldev Gajra’s book Sind’s Role in the Freedom Struggle, quoted in Freedom and Fissures: An Anthology of Sindhi Partition Poetry, notes that during the Quit India movement, at least 75 poets fought through rousing songs for the liberation of their motherland. For instance, Hundraj Lilaram Dukhayal, the national poet of Sind, stirred young blood through his memorable geets. Hyderbux Jatoi said: ‘India, our country, is our heart and soul/ May a thousand lives be sacrificed for her’ (Makhija et al. 1998).

Ajwani (1957) notes that the most remarkable phase of Sindhi contemporary poetry ‘took its rise about thirty years ago when the New Sind was born with the discovery of Mohen-jo-Daro… The honour of leading Sindhi poetry from the wilderness of Persian limitations to homely speech and natural Sindhi idiom and imagery belongs to the humble schoolmaster Kishinchand Bewas (d. 1947).’He also speaks of how poetry was moving away from the Sufistic traditions of Shah, Sachal and Sami and Persian prosody and imagery towards free verse, based on the model of European literature. Dayaram Gidumal (1857–1927) was a pioneer in this field. After Partition, the progressive trend caught on with Sindhi poets like Krishin Rahi, Arjan Shad Mirchandani, Ishwar Anchal and Moti Prakash, among others, who described the struggles of workers in fields and factories. Neo-classicism appeared in the works of Narayan Shyam, Hari Dilgir, and Inder Bhojwani. Poets like M. Kamal and Arjan Hasid became recognised as masters of the ghazal (Jotwani 1992).

Partition galvanized the poets; ‘Put in my claim for property, you say?/I claim the whole of Sind!’ wrote Lekhraj Aziz (1897–1971), author of 16 books, whose unparalleled contribution to Sindhi literature was recognised by Sindhi Sahitya Academy in 1966 (Makhija 1998). Parsram Zia (1911–1987) composed satirical poems on life in refugee camps; Arjan Shad Mirchandani, in his landmark Sahitya Akademi-award-winning work, Andho Doonhon (‘Blind Smoke’), wrote: ‘Wherever you find your people, call it home/Wherever you find Sindhis, call it your Sind’ (Makhija 1998).

Several other writers, such as Hari Dilgir, Prabhu Wafa, Krishin Rahi, Vasudev Nirmal, Narayan Shyam and Dholan Rahi brought richness to Sindhi poetry. The theme of Partition also surfaces in Mohan Gehani’s bilingual collection, Brittle Ice, where Vasdev Mohi writes in the Foreword: ‘Sadly, when Sindhis refer to the year 1947, more often than Independence, the piercing word partition appears before their moist eyes (Mohi 2014).’

Vasdev Mohi is among the distinguished Sindhi writers today (see interview). Mohi, and others like Nand Jhaveri, Vimmi Sadarangani and Indira ‘Shabnam’ Poonawala are keeping Sindhi poetry alive in India. Poonawala, who was born in Karachi, recalls growing up in tents, where the elders would cry and talk about all that they had left behind after Partition.

It is also heartening that younger poets like Mukesh Tilokani, Bharati Sadarangani and Heena Agnani are writing poetry in Sindhi. Tilokani, born in 1975, has a collection, Sachu Maree Viyo (‘Truth is Dead’), in both Arabic and Devanagiri scripts. His Pyaar Tanza Mazaak (2006) won the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi Award. Bharti Sadarangani is a winner of the 2016 Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar for her Retilo Chitu.

There are other books, such as Arun Babani’s bilingual Poems, published in Sindhi and English translation (Babani 2016). In a poem, ‘The Bag’, he writes:

There are various pockets in my bag

Drawers with labels on them

A fairly large one

Is of Sindhyat

That contains Arabic signs and symbols

Signifying

Whatever remains

Of my childhood!

In the early post-Partition era, writers like Popati Hiranandani brought a strong feminist edge to Sindhi literature. Her poem ‘Dun Hetahan Dabli’ was particularly noteworthy, and an English version of this was published in Penguin’s anthology of contemporary Indian women poets, In Their Own Voice (1993). As Hiranandani explained to me: ‘Women writers in those days were not even allowed to use the word ishq (love), but I wrote a poem “Dun Hetahan Dabli”, which means “The small box beneath the navel”. Wooden dablis were a specialty of the town of Halan in Sindh and they were beautifully painted works of art. The dabli was a box within a box within a box, whose innermost compartment usually housed valuable jewels. The poem caused a furor when it first appeared because it spoke of the central role of the uterus or womb.

Your eyes glide down below the navel,

Ah! Is it a glowing treasure house?

Or a deep mysterious cave

Where the stream of creation flows?

Prose

Sindhi prose came into its own chiefly with translations, beginning with tales of the countryside like ‘Jam Bhambo Zemindar’s Tale’ (1853) by Ghulam Hussain; imitations of Saadi’s Gulistan, such as Kewalram Salamtrai’s ‘Sookhri’ and ‘Gul’ series, and caricatures of Arabian Nights such as Akhund Lutfallah’s Gul Qand (1882). ‘Four figures must be prominently mentioned in a review of Sindhi literature as Four Pillars on which the edifice of Sindhi Prose rests,’ writes L.H. Ajwani (1957). They include Mirza Kalich Beg (1853–1929), whose Zeenat (1890) was the first original novel in the Sindhi language; Kauromal Chandanmal (1844–1916); Dayaram Gidumal; and Parmanand Mewaram, known as the ‘Addison of Sind’ for his essays and moral apologies.

The era of translations in the first half-century (1857–1907) was ushered in by lexicographers and grammarians such as Captain George Stack, author of Sindhi Grammar and Dr. Ernest Trumpp, whose grammar of the Sindhi language in English published in 1872 remained the only authentic grammar even after 130 years, according to Dr. Parso Jessaram Gidwani, author of Glimpses of Sindhi Language. Stack, in particular, was greatly impressed by Sindhi; ‘I was hitherto proud of the English language as I considered it more beautiful and a very copious language in the world… But it was really vain of me. When I learnt Sindhi I found reduplicated causal verbs and other points that gave to Sindhi a beauty distinct from most Indian languages (Gidwani 2001).’

This ‘beautiful’ language was in grave danger of being lost to many Sindhi Hindus in the post-Partition phase; with the formation of linguistic states, Sindhis realized that that there was no state support for their language. In order to save it from oblivion, therefore, they began publishing several periodicals—among them, Kahani, Nai Dunya and Kunj (quarterlies), Hindvasi and Bharatvasi (weeklies) and Hindustan (a daily). These publications did not pay writers royalties for their work, but they played the vital role of offering a platform to keep the Sindhi language alive.

The Short Story and Novel

The Sindhi short story has also seen quite an evolution, being ‘shocked into adulthood’ after Partition, in the words of Motilal Jotwani, who edited an anthology on the subject (Jotwani 1985). Prior to Partition, Jotwani pointed out, Sindhi short stories relied merely on the ideas and intentions of the author, instead of delving deeper to understand human actions; they also left almost nothing to the imagination.

Many of the stories written after Independence echoed the difficulties that Sindhis faced in struggling to survive, and the dignity with which they did so. They also reflected the camaraderie that existed between the Hindus and the Muslims; for instance, Ram Panjwani’s Mohamed ‘Gadhi-a-waro’ (‘Mohamed the Coachman’) spoke of his real-life experience of being saved by a Muslim coachman. Hiranandani’s story, ‘My Granny’, speaks of the rich ornaments that the elderly lady wore before Partition, and Sindhi delicacies such as thadal, a sweet drink made with rose petals and cardamom, among other things. When the decision is taken to send young unmarried girls to India, after Partition, the grandmother embraces her and says: ‘My child! Are you really leaving your own land?’… ‘Oh, you know that they say that even a corpse needs to be buried in the same dust from which it has grown (Shivdasani 2014)?’

Post-Partition, the novel also began to come into its own. Gobind Malhi’s pioneering work in this field was set against the backdrop of rural Sindhi life in the pre-Partition era; his novel Pakhira Valran Khan Vichyra (‘Birds Separated from the Flock’) has a protagonist who refuses to leave his motherland (Gehani 2016).

Bansi Khubchandani, a well-known critic, and author of short story collections such as Rishton Ke Gubbare and Akhran Ji Surhan, names writers like Kaladhar Mutwa, Dr. Kamla Gokhlani, Bhagwan Atlani, in the genres of fiction and Mahesh Nenwani, Mohan Himthani, Rashmi Ramani, Shrikant Sadaf, Vimmi Sadarangani, Harish Karamchandani, Vikram Shahani and Jairam Chimnani ‘Deep’ in the genre of poetry. ‘All these writers, poets are born after the 1947 partition and have made a significant contribution to Sindhi literature,’ he says.

Sindhi writers are also trying to attract new audiences to the language through robust cultural activity. Mohan Gehani’s Sindhu Dhara, performed by the prominent Sindhi dancer, Anila Sunder, brings together dance, music, drama and documentary to capture memories of Sindh. Anila Sunder has also performed several other ballets focused on Sindhi heritage and culture. Then there is Mahesh Khilwani, a well-known theatre personality born decades after Partition in 1975, who has acted in, directed and scripted several plays in Sindhi. Among the plays that he has written are Havelia Jo Matko, Tikunde Ji Chautho Kund, Khushi, Jameen, Gharjode Marriage Beauro, Bhaya Bhen, Shadia Jo Chakkar, Office Office, Dosti, Topan Mari Masi, Sangat, Deti Leti and Paisa Khapan. His Sindhi stories include ‘Natak’, ‘Hiq Mushq’, ‘Ma Fathus’, ‘Ganga’ and ‘Astha’. His skit ‘Sindh thi Yad Ache’, which he performed in Dubai, appeals to young audiences through the use of humour to highlight nostalgia for Sindh. Dr Prem Prakash, poet, dramatist and member of the Sindhi advisory board, Sahitya Akademi, has also built a reputation as a pioneer of experimental and absurd plays.

Keeping the Heritage Alive

Today, 70 years after nearly 1.2 million Sindhi Hindus left their motherland, with no hope of ever returning, they have become well-entrenched as citizens of the world, with a few committed members of the community trying to keep their heritage alive.

One organization dedicated to promoting the Sindhi language is the National Council for Promotion of Sindhi Language (NCPSL), established under the Ministry of Human Resource Development in 1994. The stated aim of the Council is to ‘promote, develop and propagate the Sindhi language and to take action for making available in Sindhi the knowledge of scientific and technological development as well as the knowledge of ideas evolved in the modern context and to advise the Government of India on issues connected with Sindhi Language’.

Among other things, NCPSL offers financial assistance to voluntary organizations for activities related to Sindhi; it purchases Sindhi books/magazines and audio-video cassettes in bulk for free distribution to educational institutes and public libraries, and offers financial assistance for the publication of Sindhi books. It also conducts Sindhi classes and offers awards to Sindhi writers for literary books. There are two Lifetime Achievement Awards of Rs.500000 each; the Sahityakar Sanman Award is given to a writer for his/her outstanding lifetime contribution to Sindhi Literature and the Sahitya Rachna Sanman is awarded to a writer for literary work in the Sindhi Language on subjects such as art/culture/education and social sciences. There are also ten Merit/Literary Awards of Rs. 1,00,000 each, given to deserving writers in recognition of their contribution in the field of Sindhi literature. In addition, there are schemes for persons with disabilities.

In April 2017, to mark the occasion of 50 years of the Sindhi language in the Indian Constitution, NCPSL and C-DAC Pune, released a CD with software tools to help Sindhi go digital. The CD features a mobile application that allows convertibility of the script from Sindhi to English on the keyboard and vice-a-versa, standardization of the Devnagari script and e-learning in the Devnagari script. ‘It now becomes very easy for writers, poets, authors, historians, students, teachers and everybody who would like to read/write/communicate in Sindhi Language, with Sindhi fonts and graphics too on all platforms,’ says Aruna Jethwani, Vice-Chairperson, NCPSL, and author of several books, including three novels and two books of poetry. ‘With the help of the Sindhi key-board many e-Books will now be made,’ she adds.

In one of her articles Ms. Jethwani asks which language in the world has the maximum number of sounds, vowels, verbs and nouns, the maximum number of letters, adjectives and adverbs. Referring to Sindhi having 52 letters of the alphabet against 35 in Hindi, she says it has 101 words for elephant, 28 commonly used words for camel, and an equal number of words for water. ‘It embraces Uzbek, Persian, Pashto, Hindi, Urdu, Kannada, Malayali (Malayalam), Tamil as its own.’ This vast vocabulary, she adds, makes it the most ‘oxygenated’ language in the world; in fact, there is a saying: ‘If you have a lung problem, speak Sindhi!’ (2015).

Dedicated individuals like Dubai-based Asha Chand, producer of several Sindhi TV serials and a cultural activist, have also done much to promote the Sindhi heritage. Chand, who is the daughter of the well-known Sindhi writers Sundri Uttamchandani and A.J. Uttam, believes that social media and the Internet are powerful tools to promote the language—and that children must be encouraged as early as possible. In 2016, her website, www.sindhisangat.com (‘a virtual state in the absence of their own physical state in India’, in her words) hosted a Sindhi Nursery Rhymes Competition. Children up to six years were required to choose any of four baits (rhymes) from the site, download the lyrics and then recite it, singing or enacting it as they chose. Parents were to upload a video of the recitation, along with the details of the child, or WhatsApp it to a specified number. The nursery rhymes were:

جوکيرپيئي Jo Kheeru Piye

پئسولڌم پٽ تان Paiso Ladhum Pat Taan

واهڙي تارا گول تارا Wah re Tara Gol Tara

مونکي ڪنھن ٿي کيرپياريو Moonkhe Kahinthe Kheeru

This proved so successful that she organized a second one in June 2017. ‘This way the little ones can pick the correct pronunciation of Sindhi—typical words such as ڄٻڳڏ,’ said Asha Chand, adding, referring to letters that have particular Sindhi intonations. ‘We all want Sindhis to speak in Sindhi and this is the best way to try, with small kids who pick up everything so very quickly.’ Chand has also launched an interactive app to teach Sindhi and has been actively campaigning for a dedicated Sindhi television channel.

Another remarkable effort to preserve the Sindhi language and culture is represented by the Indian Institute of Sindhology at Adipur, Kutch, formed by a dedicated band of writers in 1990. Their core aims were to preserve the language, literature, art and culture through a library and museum, and to promote Sindhi through the performing arts. Mohan Gehani, in his book, A Gateway to Sindhi Literature (2016), notes that in the library of the Indian Institute of Sindhology, there are about 16,000 Sindhi books, of which 15,000 are in the Sindhi-Arabic script and 1,000 in the Sindhi-Devanagiri script. The Institute has also published several books, including the Standard Trilingual Dictionary (Sindhi-Hindi-English) with Dr. Satish Rohra as Chief Editor, Sindhi Folk Tales by Pritam Varyani, and Something about Sindh and Sindhis, by Sahib Bijani.

The organization reaches out to children through the Sadhu Hiranand Navalrai Academy, an English school that teaches Sindhi. There is also a tranquil residential complex for writers called Maleer. ‘It is my dream that Sindhology soon becomes a replica of Mohen-jo-Daro and is able to impart knowledge of the over 7,000-year-old Sindhu civilization among young inheritors,’ wrote Dr Ram Buxani, Chairman, Indian Institute of Sindhology, in the souvenir publication for the silver jubilee celebrations in December 2015.

In the year 2011, I had the opportunity to visit the Institute and spend time at Maleer, where these stalwarts of Sindhi literature stayed. I was privileged to meet Lakhmi Khilani; Moti Prakash and his wife Kala Prakash; Dr Satish Rohra; Pritam Varyani and Sahib Bijani. All these writers had lived through Partition; they had played a crucial role in building the Institute and preserving their culture. I wanted to hear their stories, and learn more about the work they were doing; my amateur video camera made a handy companion, even if it meant trying to record the videos over the sounds of passing trains and boisterous children at the school attached to the premises.

Lakhmi Khilani spoke to me of how the Institute was conceived; Moti Prakash recounted the traumas of his Partition experience; Kala Prakash grew nostalgic about how young writers like her in the post-Partition era kept their tryst with writing alive; Dr. Satish Rohra spoke of the importance of the dictionary project, which, in fact, saw its final entry minutes before our interview; and Pritam Varyani found his throat choked, decades later, recalling how he escaped from the riots and survived on the ‘charity’ of rotten grain.

I also met younger writers such as Vimmi Sadarangani and Mukesh Tilokani. Vimmi, poet and author of more than 11 books, teaches Sindhi at the Tolani College of Arts and Science, and has written a feature on post-Partition Sindhi poetry for this module. Mukesh, the librarian at the Institute, is a recognized poet. It was also through the Institute that I later connected with Bhopal-based Mohan Gehani, distinguished author of several books on Sindhi literature; his article on the post-Partition Sindhi short story features here.

All these writers, of different ages, are working to keep the culture alive in a post-Partition world. Their efforts are bearing fruit, but slowly. Thanks to Partition, three generations of Sindhis have lost vital links to their culture and language, and while writers continue to write, they have few readers.

In a world of commerce where English is paramount, and Sindhi has little or no role to play, youngsters are often reluctant to learn their mother tongue. A few post-Partition Sindhis are becoming aware of this loss and trying to redress the balance, to reclaim the language at least for future generations. As London-based Devendra Kodwani says: ‘There is a very rich body of literature, rich Sindhi culture embedded in the Sindhi language, which is part of the finest traditions and human achievements which we must enjoy and pass on to the future generations (2015:53).’

____________________

Menka Shivdasani, a Mumbai-based poet and journalist, has published three collections of poetry—’Nirvana at Ten Rupees’, ‘Stet’ and ‘Safe House’. She has edited an anthology of women’s writing for SPARROW, and two anthologies of contemporary Indian poetry for the American e-zine, www.bigbridge.org. She is also co-translator of ‘Freedom and Fissures’, an anthology of Sindhi Partition poetry (Sahitya Akademi). In 1986, she co-founded Poetry Circle in Mumbai.

Menka Shivdasani, a Mumbai-based poet and journalist, has published three collections of poetry—’Nirvana at Ten Rupees’, ‘Stet’ and ‘Safe House’. She has edited an anthology of women’s writing for SPARROW, and two anthologies of contemporary Indian poetry for the American e-zine, www.bigbridge.org. She is also co-translator of ‘Freedom and Fissures’, an anthology of Sindhi Partition poetry (Sahitya Akademi). In 1986, she co-founded Poetry Circle in Mumbai.

Courtesy: Shahpedia