Besides the new book titled ‘The Politics of Trash’, many other books on have already been published on garbage politics in other countries including India and Lebanon.

Sindh Courier

A new book ‘The Politics of Trash’ explains how municipal trash collection solved odorous urban problems using non-governmental and, often, unseemly means. Focusing on the persistent problem of filth and the frustration of generations of reformers unable to clean their cities, Patricia Strach and Kathleen S. Sullivan tell a story of dirty politics and administrative innovation that made rapidly expanding American cities livable.

The solutions professionals recommended to rid cities of overflowing waste cans, litter-filled privies, and animal carcasses were largely ignored by city governments. Where the efforts of sanitarians, engineers, and reformers failed, the habits and tools of corruption as well as gender and racial hierarchies proved efficacious.

Corruption often provided the political will to public officials to erect garbage collection programs. Effective waste collection involves translating municipal imperatives into private habits and new arrangements in homes and other private spaces. To change domestic habits, officials relied on gender hierarchy to make the woman of the white, middle-class household in charge of sanitation. When public and private trashcans overflowed, racial and ethnic prejudice singled out scavengers, garbage collectors, and neighborhoods by race. These early informal efforts were slowly incorporated into formal administrative processes that created the public-private sanitation systems that prevail in most American cities today.

This consideration of municipal garbage collection offered in ‘The Politics of Trash’ reveals how political development relies on undemocratic means with long-term implications for further inequality. The resources that cleaned American cities also show the tenuous connection between political development and modernization.

Patricia Strach is Professor of Political Science and Public Administration & Policy at the University at Albany, SUNY. She is the author of Hiding Politics in Plain Sight, Corporate Influence, Breast Cancer Policymaking, and All in the Family.

Kathleen S. Sullivan is Associate Professor of Political Science at Ohio University. She is the author of Constitutional Context.

The books on such topics are not rare. Earlier, a book ‘The Politics of Garbage: A Community Perspective on Solid Waste Policy Making’, authored by Larry S. Luton was published in 1996.

Increased environmental awareness, more demands on local governments, a newly invigorated citizen activism, and a decaying and overburdened infrastructure have made taking care of our garbage one of the major policy making challenges facing local communities. Luton used the case study of Spokane WA to analyze the public administration and socio-political context of solid waste policy making. Luton’s thorough exploration of Spokane’s experience as opens a window onto contemporary issues of solid waste management as well as the complex social and political environment in which public administrators must operate. His integration of systems theory in the analysis adds to the book’s value as a teaching tool for courses on policy making, urban planning, public administration, and the environment. He examines the complex combination of ecological, political, social and relational dynamics that affect such policies, providing insight into inter-governmental public policy making.

Increased environmental awareness, more demands on local governments, a newly invigorated citizen activism, and a decaying and overburdened infrastructure have made taking care of our garbage one of the major policy making challenges facing local communities. Luton used the case study of Spokane WA to analyze the public administration and socio-political context of solid waste policy making. Luton’s thorough exploration of Spokane’s experience as opens a window onto contemporary issues of solid waste management as well as the complex social and political environment in which public administrators must operate. His integration of systems theory in the analysis adds to the book’s value as a teaching tool for courses on policy making, urban planning, public administration, and the environment. He examines the complex combination of ecological, political, social and relational dynamics that affect such policies, providing insight into inter-governmental public policy making.

Larry S. Luton is professor and program director of the Graduate Program in Public Administration at Eastern Washington University.

Another book ‘Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash’ authored by Gillian Whiteley was published in 2011.

Trash, garbage, rubbish, dross, detritus — in this enjoyably radical exploration of junk, Gillian Whiteley re-thinks art’s historical and present appropriation of junk within our eco-conscious and globalized culture. She does this through an illustrated exploration of particular materials, key moments and locations and the telling of a panoply of trash narratives. Found and ephemeral materials are primarily associated with assemblage — object-based practices which emerged in the mid-1950s and culminated in the seminal exhibition “”The Art of Assemblage”” in New York in 1961. With its deployment of the discarded and the filthy, Whiteley argued, assemblage has been viewed as a disruptive, transgressive artform that engaged with narratives of social and political dissent, often in the face of modernist condemnation as worthless kitsch. In the Sixties, parallel techniques flourished in Western Europe, the US and Australia but the idiom of assemblage and the re-use of found materials and objects — with artist as bricoleur — is just as prevalent now. This is a timely book that uncovers the etymology of waste and the cultures of disposability within these economies of wealth.

Trash, garbage, rubbish, dross, detritus — in this enjoyably radical exploration of junk, Gillian Whiteley re-thinks art’s historical and present appropriation of junk within our eco-conscious and globalized culture. She does this through an illustrated exploration of particular materials, key moments and locations and the telling of a panoply of trash narratives. Found and ephemeral materials are primarily associated with assemblage — object-based practices which emerged in the mid-1950s and culminated in the seminal exhibition “”The Art of Assemblage”” in New York in 1961. With its deployment of the discarded and the filthy, Whiteley argued, assemblage has been viewed as a disruptive, transgressive artform that engaged with narratives of social and political dissent, often in the face of modernist condemnation as worthless kitsch. In the Sixties, parallel techniques flourished in Western Europe, the US and Australia but the idiom of assemblage and the re-use of found materials and objects — with artist as bricoleur — is just as prevalent now. This is a timely book that uncovers the etymology of waste and the cultures of disposability within these economies of wealth.

Gillian Whiteley is a curator and is lecturer in visual and material culture at Loughborough University. Her publications include Telling Stories: Theories and Criticism, Cinematic Essay, Objects and Narrative (2009). She is a regular contributor to The Art Book, for which during 2009 she has been Honorary Editor.

Matthew Gandy, a lecturer in geography at the University of Sussex, also authored a book titled ‘Recycling and the Politics of Urban Waste’.

According to him the affluence of western society has given rise to unprecedented quantities of waste, presenting one of the most intractable environmental problems for contemporary society. This book examines recycling and municipal waste management in three major cities: London, New York and Hamburg. A range of political and economic issues are examined to illustrate how any reduction in the size of the waste stream in order to achieve more equitable and environmentally sustainable patterns of resource use is incompatible with the current emphasis in the use of the market for environmental protection. The case studies show how, contrary to the hopes of many environmentalists and policy makers, municipal waste management is moving steadily towards the profitable option of incineration with energy recovery, rather than the recycling of materials or waste reduction at source. The evidence suggests that the achievement of a more sustainable pattern of recycling and waste management policy would demand a fundamental change in public policy, to give government a more active role in environmental protection.

According to him the affluence of western society has given rise to unprecedented quantities of waste, presenting one of the most intractable environmental problems for contemporary society. This book examines recycling and municipal waste management in three major cities: London, New York and Hamburg. A range of political and economic issues are examined to illustrate how any reduction in the size of the waste stream in order to achieve more equitable and environmentally sustainable patterns of resource use is incompatible with the current emphasis in the use of the market for environmental protection. The case studies show how, contrary to the hopes of many environmentalists and policy makers, municipal waste management is moving steadily towards the profitable option of incineration with energy recovery, rather than the recycling of materials or waste reduction at source. The evidence suggests that the achievement of a more sustainable pattern of recycling and waste management policy would demand a fundamental change in public policy, to give government a more active role in environmental protection.

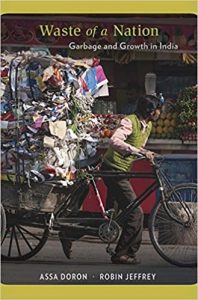

Meanwhile, Assa Doron and Robin Jeffrey documented in their book ‘Waste of a Nation: Garbage and Growth in India’ the state’s failure to ameliorate its sanitation problems. According to them the failure doesn’t necessarily derive from cultural convention. It is more often the result of shady economic relationships between public and private interests. They contend that time and again, the state has failed to invest in local waste economies, opting instead to outsource solid waste management to private enterprise.

Yet another book ‘Garbage Politics’ authored by Ziad Abu-Rish states that mounds of garbage had been piling up across Beirut and the towns of Mount Lebanon to the capital’s east in July 2015. While not without precedent in poorer neighborhoods, such heaps of rubbish had never appeared in more affluent areas. By mid-August, Lebanese government officials, businesspeople, activists, residents and media outlets were all speaking about a garbage crisis. Some observers took a benign view of the accumulating trash, seeing it as one more symptom of the alleged absence of a state in Lebanon. For those inclined to more sinister interpretations, the crisis was the logical outcome of the purported strain that more than 1 million Syrian refugees have placed on Lebanese infrastructure. As the refuse rotted in the streets and political debates remained stuck in the above terms, a broad protest movement consolidated itself. Popular mobilizations challenged both benign and sinister accounts and called into question the conventional wisdom about the state, social order and politics in Lebanon.

Yet another book ‘Garbage Politics’ authored by Ziad Abu-Rish states that mounds of garbage had been piling up across Beirut and the towns of Mount Lebanon to the capital’s east in July 2015. While not without precedent in poorer neighborhoods, such heaps of rubbish had never appeared in more affluent areas. By mid-August, Lebanese government officials, businesspeople, activists, residents and media outlets were all speaking about a garbage crisis. Some observers took a benign view of the accumulating trash, seeing it as one more symptom of the alleged absence of a state in Lebanon. For those inclined to more sinister interpretations, the crisis was the logical outcome of the purported strain that more than 1 million Syrian refugees have placed on Lebanese infrastructure. As the refuse rotted in the streets and political debates remained stuck in the above terms, a broad protest movement consolidated itself. Popular mobilizations challenged both benign and sinister accounts and called into question the conventional wisdom about the state, social order and politics in Lebanon.

The protest movement began in late July and early August as a series of small demonstrations organized by a group called You Stink. The group established an online repository for digital video and photographs documenting the garbage crisis. ‘You Stink’ movement also engaged in creative actions such as delivering bags of trash to the homes and offices of various ministers. Yet the initial rallies drew no more than a hundred people. A protest on August 19 was a turning point, as the government cracked down hard. Video of security forces violently confronting protesters went viral, leading family, friends and allies of the ‘You Stink’ organizers to join the next demonstration on August 22. But You Stink supporters were not the only ones who took to the streets. The participants now included formal groupings of feminists, queer activists, leftists and environmentalists, as well as residents of neighborhoods that have borne the brunt of the state’s withdrawal of services and its routine repression. Security forces tried to disperse the crowds with batons, sound grenades, water cannons and rubber bullets.

__________________

Source: Cornell Press, Amazon, Tandfo Online, MERIP, Routledge