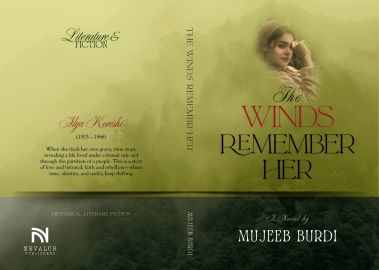

The Winds Remember Her (Novel)

Book ‘The Winds Remember Her’, authored by Mujeeb Burdi, is a Haunting Elegy of Memory, Love, and History

Book Review by: Asif Bhatti

‘The Winds Remember Her’ by Mujeeb Burdi is a haunting work of historical literary fiction—one that refuses to obey the ordinary boundaries of time, history, or the self. It opens with an image unforgettable in its surreal precision: Alya Koreshi, sixty-three years old, walks to the churchyard in Reiyat, a forgotten colonial hill town, and finds her own grave bearing today’s date. From that moment, the novel folds time inward upon itself, dissolving the walls between life and death, past and present, memory and hallucination. This discovery is not only a narrative spark but a philosophical wound: the living woman confronting her own mortality, her own inscription in history, becomes the central metaphor for a nation and a people whose identities were rewritten by empire, Partition, and time itself.

Reiyat, the setting, is less a place than a state of being—a mountain town carved by the British in the nineteenth century. This half-living town wanders life: Alya Koreshi, daughter of Moosa, an Indian Muslim soldier in the British Indian Army, and Margaret, an Englishwoman whose love defied the world’s classifications. Through this mixed lineage, Alya inherits contradiction as destiny, her very existence a fragile truce between colonizer and colonized, faith and skepticism, memory and amnesia. Burdi handles these inherited paradoxes not as political abstractions but as lived experience. The prose carries a stillness that feels almost geological—patient, precise, textured by melancholy. The novel’s rhythm is deliberate, its paragraphs sculpted like terraces on the mountainside, each revealing a view of history both intimate and vast.

Reiyat, the setting, is less a place than a state of being—a mountain town carved by the British in the nineteenth century. This half-living town wanders life: Alya Koreshi, daughter of Moosa, an Indian Muslim soldier in the British Indian Army, and Margaret, an Englishwoman whose love defied the world’s classifications. Through this mixed lineage, Alya inherits contradiction as destiny, her very existence a fragile truce between colonizer and colonized, faith and skepticism, memory and amnesia. Burdi handles these inherited paradoxes not as political abstractions but as lived experience. The prose carries a stillness that feels almost geological—patient, precise, textured by melancholy. The novel’s rhythm is deliberate, its paragraphs sculpted like terraces on the mountainside, each revealing a view of history both intimate and vast.

From its earliest pages, the novel’s language establishes a tone of elegiac reverence. The descriptions of Reiyat evoke decay with a painter’s restraint: “Moss devours the roofs of the colonial cottages, shutters groan open with reluctance, and the old garrison still looms like a ruined watchman.” Yet within this stillness breathes persistence—a moral endurance that becomes the book’s heartbeat. When Alya kneels before her own grave, the scene becomes emblematic of South Asia’s twentieth century: the living and the dead intermingled, each generation inheriting both memory and erasure. The realism of the opening soon dissolves into a fluid stream of temporal dislocation, and Burdi achieves something rare—the precision of realism married to the logic of dreams.

As Alya falls through time, we witness the unfolding of a life marked by love and rebellion, framed within the tectonic shifts of the subcontinent. Burdi’s handling of time resembles Faulkner or Woolf at their most daring, yet the spirit of the novel remains distinctly South Asian, more akin to the ghostly lyricism of Qurratulain Hyder or the psychological depth of Anita Desai. Time in The Winds Remember Her is not linear but circular, an eternal recurrence of the same sorrows. When Alya moves from 1966 back to 1947 and then to 1909, her life becomes a palimpsest—every layer of experience bleeding through to the next. We witness her childhood laughter with Mary Clarke, the missionary’s daughter, before witnessing Mary’s death in a riot decades later. We see her father’s growing rigidity, his transformation from a soldier of the Empire into a bitter nationalist, alienated from both the British he once served and the Christian wife he once adored. Through such moments, Burdi maps the psychological geography of colonialism—not as an abstract force but as a slow corrosion of intimacy.

The love story between Alya and William Ashcroft, a British officer, stands at the emotional core of the novel. Their first meeting, beneath a storm-torn umbrella, carries all the delicacy of doomed tenderness. It is a romance burdened from its first glance by history’s shadow; every word between them seems spoken against a background of crumbling empires. Burdi writes their exchanges with restraint, never indulging in sentimentality. The power of their love lies precisely in its impossibility—in the quiet, trembling space between what they desire and what the world will allow.

Equally compelling is the novel’s exploration of memory as a form of haunting. The transitions between time periods occur without warning, often mid-paragraph, creating a sensation of drifting through consciousness. This technique might have disoriented a lesser writer, but Burdi sustains coherence through emotional truth. Each temporal shift is anchored by sensory continuity—the smell of rain, the sound of a bell, the feel of cold stone beneath her hand. These recurrences become the novel’s connective tissue, implying that memory itself is a landscape one walks through, not a sequence one recalls. Even as time collapses, Alya’s humanity persists, her voice steady amid the dissolution. In this, Burdi achieves a rare fusion of structure and theme: the novel’s form enacts its philosophy. Just as history refuses closure, so does the narrative resist containment.

The political dimension of the novel emerges gradually, never declaimed but lived. Through Moosa Koreshi, the novel exposes the contradictions of colonial service—the pride of soldiering for an empire that denies one’s humanity, the seduction of discipline and loyalty that ultimately curdles into self-contempt. Through Margaret, it interrogates the position of the colonial woman who crosses racial and cultural lines, condemned by both societies. Their marriage, tender yet fractured, becomes an allegory for a hybrid nation struggling to reconcile its halves. When Partition arrives, the devastation is not described through riots alone but through domestic estrangement. Moosa’s refusal to step into his wife’s Christian grave in 1947 is one of the most devastating moments in the novel—a gesture of faith hardened into cruelty, love disfigured by ideology. Burdi writes the confrontation between father and daughter at the church gate with a power that recalls the tragic clarity of Greek drama. “Pakistan happened,” he tells her, and in those two words the novel condenses the entire madness of the twentieth century: a map drawn in blood that severs not just land but souls.

Reiyat itself becomes a metaphor for postcolonial liminality—a town existing outside time, forgotten by both colonizer and nation. Its broken telegraph lines and silent bells mirror the disconnection of its people from history’s grand narrative. Yet in its decay, Reiyat retains dignity; it refuses erasure. Burdi’s portrayal of place is not decorative but metaphysical: the town watches, listens, remembers. Its silence becomes the moral witness to the violence of forgetting.

The novel’s style deserves particular admiration. The prose is steeped in rhythm, yet never ornamental for its own sake. It balances lyricism with clarity, intimacy with grandeur. The sentences often unfold like slow incantations, accumulating emotional gravity through repetition and variation. The dialogue, by contrast, is taut and natural, often infused with quiet irony. The language the book feels simultaneously crafted and organic, its English lyrical without imitation. Burdi’s restraint with metaphors and his precision in emotional texture give the novel a timeless literary poise. In many passages—Alya’s collapse in the storm, Moosa’s silence at the gate, the ghostly repetitions of her own death—the prose approaches the poetic intensity of sacred text. The reader senses that this is not just fiction but life transcribed into art.

What makes the book remarkable, however, is its moral clarity. It refuses the cheap consolations of nationalism or nostalgia. It acknowledges the grandeur of independence and the tragedy of what it cost. It treats faith with reverence but also with suspicion, revealing how easily belief turns into violence. It honors love without romanticizing its futility. In Burdi’s world, no one is wholly right or wrong; everyone is shaped by forces beyond comprehension. Moosa’s rigidity is born from betrayal, Margaret’s sorrow from exile, William’s gentleness from inherited guilt, and Alya’s strength from their combined pain. She stands as the book’s moral center not because she is pure but because she endures, questioning to the end what it means to belong. Her declaration—“I am Alya Koreshi, and I am still alive”—resonates far beyond the graveyard where she utters it.

The novel spans six decades and yet never loses focus on the inner life of its protagonist. We witness the colonial era’s hauteur, the idealism of early nationalist movements, the devastation of Partition, and the disillusionment of early Pakistan. Each historical moment is refracted through human experience—never explained through exposition but revealed in gesture, dialogue, silence. The cumulative effect is staggering: history not as chronology but as atmosphere, as haunting continuity. Every event echoes backward and forward through time.

What distinguishes the novel from much of contemporary historical fiction is its refusal to domesticate trauma into narrative closure. The book ends as it begins—with ambiguity, with the same grave that may be real or imagined, with the same question unresolved. Does Alya die in 1966, or has she already transcended death through remembrance? The novel does not answer, because the answer itself is irrelevant. This circularity gives the novel its haunting power—it leaves the reader suspended between grief and awe, unable to let go.

There are moments when the narrative’s density may challenge readers accustomed to straightforward chronology. Its shifting times, recurrent imagery, and hallucinatory transitions require attention and surrender. But to yield to its rhythm is to experience literature in its highest form—where language, history, and emotion converge into something elemental. Few novels in recent memory have captured with such precision the condition of being between worlds, between faiths, between centuries. In Alya Koreshi, Burdi gives us a heroine for whom existence itself is rebellion, whose memory outlives her body, whose grave becomes not an ending but a door.

The Winds Remember Her stands among the most accomplished literary works to emerge from South Asia in recent years—a book that will not be easily forgotten. The novel demands patience, not because it is obscure, but because it is vast. Its rewards are profound. When one finishes the final page, one feels not that a story has ended but that one has traversed time itself and returned altered.

__________________