In India, Sindhis are perceived as a shallow caricature. Sindhi Tapestry is an attempt to document the rich historical realities of their lives in Sindh and the heterogeneity of the community.

By Madhusree Ghosh

For generations, the story of India’s Sindhis – those displaced by Partition and welcomed in India after 1947 – followed a familiar script. There were heart-breaking accounts of the horrors of 1947 families ripped apart, fortunes lost, lives uprooted. Then came tales of refugees – camps, chaos, struggles, the stirrings of new life. Then stories of hope – flourishing of educational institutions, businesses and traditions – And later, reflections on lives spent in lands now divided by a hostile border, and of recreating the family recipe for flatbreads like koki.

So in June, when photographer Ritesh Uttamchandani proposed an idea of a new anthology about the community, to author Saaz Aggarwal, they both knew it had to be different. Aggarwal is known for her literary work, Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland. But with the community now spread across the world, the ideas of identity and belonging cover much more than a single homeland. She put out word, asking community members to contribute essays, memories, poems and stories covering what it might mean to be a Sindhi today.

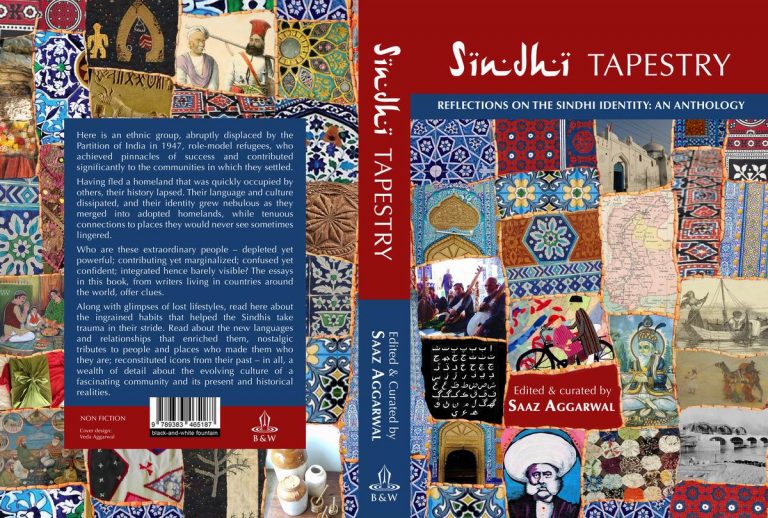

By December 2020, she had enough material to publish Sindhi Tapestry: an anthology of reflections on the Sindhi identity. It collects 60 contributions, from academics, those in creative professions, doctors, engineers, armed forces personnel and businessmen. The stories come from as far away as Puerto Rico, Chile, Japan, The Philippines and the Canary Islands. There are also ones from Sindh and parts of India. There are chapters that look at the comforting rituals of worship, through traditional (and uniquely Sindhi) utensils or items of furniture brought from Sindh or later acquired out of sentimentality. And there are new memories and boundaries, being forged as the community celebrates, its heterogeneous identity.

Aggarwal spoke about putting the book together and connecting with a new generation of Sindhis. Excerpts:

What makes Sindhi Tapestry different from other works about Sindhis?

In India, Sindhis are perceived as a shallow caricature. Sindhi Tapestry is an attempt to document the rich historical realities of their lives in Sindh and the heterogeneity of the community, through short pieces of writing. It also has rare photographs, such as the construction of the Sukkur Barrage, contributed by Radhika Chakraborty. Much of the history of the Hindu Sindhis was destroyed by the events following Partition, and this album is extremely valuable.

Many contributors have written about how their families faced Partition and the new lives they built; others write about their own journeys of self-exploration. Ritesh Uttamchandani, whose idea this collection was, writes about how his father was the key witness in a burglary case when the judge pronounced, in Sindhi, that a child would certainly not lie. Trisha Lalchandani, a PhD student, writes about how differently colonial accounts paint Sindhis from the impressions created by folk tales.

How is the new generation navigating and preserving identity differently?

Tarun Sakhrani opens his essay with an encounter with a Sindhi taxi driver in New York and goes on to talk about how the elders of his family dealt with Partition, and how family food rituals helped him to navigate the lockdown with his children.

Lavish hospitality and a shared history of food are something many Sindhi families have passed on to new generations effortlessly along with values of sustainability, hard work and enterprise. Language and cultural heritage are usually passed on similarly – but for a community with no place where their mother tongue is spoken on the streets, it happened only in rare cases.

Nikhil Bhojwani, who can tell when Sindhi is being spoken but cannot understand the words, has written about cherished family stories, illustrious family ancestors, and the family values his children have inherited through these.

Issues of identity and defining oneself must be challenging for those abroad…

There are global Sindhi communities that have become ‘Hinduised’, a step away from the syncretic faith of Sindh, influenced by Hindu communities where they settled after Partition. But many are being assimilated into global cultures, speaking local languages, cooking local food, and with local partners. Dirven Hazari, who produces brilliant spoofs on his video channel Sindhionism, writes that as per his YouTube analytics, he has fans in around 170 countries. A pleasant surprise, since he jokes: “I always thought Sindhis lived only in Ulhasnagar”.

Where do you think the Sindhi legacy now resides?

Many of the new generation understand the language, but few speak and even fewer read and write it. The treasures of Sindhi literature and philosophy, flourishing in Sindh, are all but lost to the diaspora.

As for the many institutions built by the Hindu Sindhis, schools, colleges, hospitals, cooperative housing societies, civic infrastructure, research institutions, business philanthropic initiatives – communities around the world have inherited this legacy.

_______________________

Courtesy: Hindustan Times (Published on March 8, 2021)